He really wore a black hat, this particular villain; he was known and recognized throughout the district around Fredericksburg and the German settlements in Gillespie County – by his fine, black beaver hat. Which was not furry, as people might tend to picture immediately – but made of felt, felt manufactured from the hair scraped from beaver pelts. This had been the fashion early in the 19th century, and made a fortune for those who sent trappers and mountain-men into the far, far west, hunting and trapping beaver. The fashion changed – and the far-west fur trade collapsed, but I imagine that fine hats were still made from beaver felt. And J.P. Waldrip was so well-known by his hat that he was buried with it.

He really wore a black hat, this particular villain; he was known and recognized throughout the district around Fredericksburg and the German settlements in Gillespie County – by his fine, black beaver hat. Which was not furry, as people might tend to picture immediately – but made of felt, felt manufactured from the hair scraped from beaver pelts. This had been the fashion early in the 19th century, and made a fortune for those who sent trappers and mountain-men into the far, far west, hunting and trapping beaver. The fashion changed – and the far-west fur trade collapsed, but I imagine that fine hats were still made from beaver felt. And J.P. Waldrip was so well-known by his hat that he was buried with it.

There is not very much more known about him, for certain. I resorted to making up a good few things, in making him the malevolent presence that he is in The Adelsverein Trilogy – a psychopath with odd-colored eyes, a shifty character, suspected of horse-thievery and worse. I had found a couple of brief and relatively unsubstantiated references to him as a rancher in the Hill Country, before the Civil War, of no fixed and definite address. That was the frontier, the edge of the white man’s civilization. Generally the people who lived there eked out a hardscrabble existence as subsistence farmers, running small herds of near-wild cattle. There was a scattering of towns – mostly founded by the German settlers who filled up Gillespie the late 1840s, and spilling over into Kendall and Kerr counties. The German settlers, as I have written elsewhere, brought their culture with them, for many were educated, with artistic tastes and sensibilities which contrasted oddly with the comparative crudity of the frontier. They were also Unionists, and abolitionists in a Confederate state when the Civil War began – and strongly disinclined to either join the Confederate Army, or take loyalty oaths to a civil authority that they detested. Within a short time, those German settlers were seen as traitors, disloyal to the Southern Cause, and rebellious against the rebellion. They paid a price for that; martial law imposed on the Hill Country, and the scourge of the hangerbande, the Hanging Band. The Hanging Band was a pro-Confederate lynch gang, which operated at the edges of martial and perhaps with encouragement of local military authorities.

J.P. Waldrip was undoubtedly one of them – in some documents he is described as a captain, but whether that was a real military rank, or a courtesy title given to someone who raised a company for some defensive or offensive purpose remains somewhat vague. None the less, he was an active leader among those who raided the settlements along Grape Creek, shooting one man and hanging three others – all German settlers, all of them of Unionist sympathies. One man owned a fine horse herd, another was known to have money, and the other two had been involved in a land dispute with pro-Confederate neighbors. Waldrip was also recognized as being with a group of men who kidnapped Fredericksburg’s schoolteacher, Louis Scheutze, from his own house in the middle of town, and took him away into the night. He was found hanged, two days later – his apparent crime being to have objected to how the authorities had handled the murders of the men from Grape Creek. It was later said bitterly, that the Hanging Band had killed more white men in the Hill Country during the Civil War than raiding Indians ever did, before, during and afterwards.

And two years after the war ended, J.P. Waldrip appeared in Fredericksburg. No one at this date can give a reason why, when he was hated so passionately throughout the district, as a murderer, as a cruel and lawless man. He must have known this, known that his life might be at risk, even if the war was over. This was the frontier, where even the law-abiding and generally cultured German settlers went armed. Why did he think he might have nothing to fear? Local Fredericksburg historians that I put this question to replied that he was brazen, a bully – he might have thought no one would dare lift a hand against him, if he swaggered into town. Even though the Confederacy had lost the war, and Texas was under a Reconstruction government sympathetic to the formerly persecuted Unionists – what if he saw it as a dare, a spit in the eye? Here I am – what are y’all going to do about it?

What happened next has been a local mystery ever since, although I – and the other historical enthusiasts are certain that most everyone in town knew very well who killed J.P. Waldrip. He was shot dead, and fell under a tree at the edge of the Nimitz Hotel property. The tree still exists, although the details of the story vary considerably: he was seen going into the hotel, and came out to smoke a quiet cigarette under the tree. No, the shooter saw him going towards the hotel stable, perhaps to steal a horse. No, he was being pursued by men of the town, after the sheriff had passed the word that he was an outlaw, and that anyone killing him would face no prosecution from the law. Waldrip was shot by a sniper, from the cobbler’s shop across Magazine Street — no, he was shot from the upper floor of another building, diagonally across Main Street. He was felled by a single bullet and died instantly, or was shot many times and lived long enough to plead “Please don’t shoot me any more”. I have created yet another rationale for his presence, and still another dramatic story of his end under the oak tree next to the Nimitz Hotel. I have a feeling this version will, over time be added to the rest. Everyone who knew the truth about who shot Waldrip, why he came back to town, how the town was roused against him, and what happened afterwards, all those people took the knowledge of those matters to their own graves, save for tantalizing hints left here and there for the rest of us to find. The whole matter about the two men who may have actually fired the shot — or shots — was kept secret for decades, for fear of reprisals from those of his friends and kin who had survived the war. This was Texas, after all, where feuds and range wars went on for generations.

So James P. Waldrip was buried – with his hat – first in a temporary grave, not in the town cemetery – and then moved to a secret and ignominious grave on private property. The story is given so that none of his many enemies might be tempted to desecrate it, but I think rather to make his ostracism plain and unmistakable, in the community which he and his gang had persecuted.

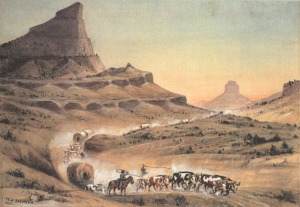

The greatest part of the goods carried in a typical emigrant wagon was food. Assuming a six-month long journey, an early guidebook writer advised 200 lbs of flour, 150 pounds of bacon, 10 pounds of coffee, 20 of sugar and 10 of salt per each adult, at a minimum; a schedule providing a monotonous diet on variants of bread, bacon and coffee, three meals a day. More elaborate checklists afforded a little more variety, not to mention edibility, suggesting such things as dried, chipped beef, rice, tea, dried beans, molasses, dried codfish, dried fruit, baking soda, vinegar, cheese, cream of tarter, pickles, mustard, ginger, corn-meal, hard-tack, and well-smoked hams. Canned food was a science still in the experimental stage then… and such things were expensive, heavy, and seldom included. A number of resourceful families brought along milk cows, and thus had milk and butter for at least the first half of the trail. Recommended kitchen included an iron cooking kettle, fry-pan, coffee pot, and tin camp plates, cups, spoons and forks. Small stoves were sometimes brought along, but more usually discarded as an unnecessary weight. A coffee mill would have been needed; so would a canvas tent.

The greatest part of the goods carried in a typical emigrant wagon was food. Assuming a six-month long journey, an early guidebook writer advised 200 lbs of flour, 150 pounds of bacon, 10 pounds of coffee, 20 of sugar and 10 of salt per each adult, at a minimum; a schedule providing a monotonous diet on variants of bread, bacon and coffee, three meals a day. More elaborate checklists afforded a little more variety, not to mention edibility, suggesting such things as dried, chipped beef, rice, tea, dried beans, molasses, dried codfish, dried fruit, baking soda, vinegar, cheese, cream of tarter, pickles, mustard, ginger, corn-meal, hard-tack, and well-smoked hams. Canned food was a science still in the experimental stage then… and such things were expensive, heavy, and seldom included. A number of resourceful families brought along milk cows, and thus had milk and butter for at least the first half of the trail. Recommended kitchen included an iron cooking kettle, fry-pan, coffee pot, and tin camp plates, cups, spoons and forks. Small stoves were sometimes brought along, but more usually discarded as an unnecessary weight. A coffee mill would have been needed; so would a canvas tent.

Recent Comments