Directly from the author – Paperback – 3 Volumes – $44.00 + 5.00 S/H

At Barnes & Noble

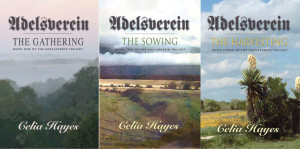

The Gathering – The Sowing – The Harvesting – The Gathering (German Translation) – Complete Trilogy (hardcover)

From the Old World to the New

The frontier would challenge them. Brutal war would test them, in a crucible of fire. But they would endure and build. They would prosper and in the end … They would become Americans!

The Adelsverein Trilogy, is a saga of family and community loyalties, and the challenge of building a new life on the hostile frontier. They come from Germany to Texas in 1847, under the auspices of the “Mainzer Adelsverein” – the society of noblemen of Mainz, who seek to fill a settlement in Texas with German farmers and craftsmen.

Christian “Vati” Steinmetz, the clockmaker of Ulm in Bavaria, has brought his sons and daughters: Magda – passionate and courageous, courted by Carl Becker, a young frontiersman with a dangerous past. Her sister Liesel wants nothing more than to be a good wife to her husband Hansi, a stolid and practical farmer called by circumstances to be something greater, in the boom years of the great cattle ranches. Their brothers Friedrich and Johann, have always been close — in the Civil War, one will wear Union blue, the other Confederate grey homespun — but never forget they are brothers. And finally, there is Vati’s adopted daughter Rosalie, whose life ends as it began – in tragedy. But Vati’s family will will survive and ultimately triumph. They will make their mark in Texas, their new land.

Adelsverein — It’s about love and loss, joy and grief . . . and the sometimes wrenching process of becoming American.

From The Gathering: Chapter 2 – Gehe Mit Ins Texas

“Adelsverein!” exclaimed Vati, with enthusiasm burning hectically in his eyes behind his thick spectacles. “It may be the answer to our dilemma, the situation in which we find ourselves! Magda, dearest child, you must read this. It’s all here. What they are offering. Everything and a new life and land, besides! Land enough for all of you children to have a decent and prosperous life, and I should not have to take myself away to the city.”

“Yes, Vati,” his stepdaughter sighed. ”I’ll read it most carefully, before Hansi and Mutti see it.” She took the slim pamphlet from him, although she was already carrying his box of watch-making tools, as the two of them walked along the narrow village street, of which Albeck only had four, including the one which led to the city of Ulm. A late snowstorm scattered a few feather-like flakes around them, which whispered as they settled on the muddy and oft-churned ground. They stepped aside as a pair of bullocks pulling a sledge with a load of manure went past.

“Is that not Peter Frimmel already mulching his field?” Vati squinted after them. “It is early, yet, I think.”

“It’s March, Vati,” Magda answered. She was a tall young woman with the ink-black hair and dark hazel eyes of her father, Mutti’s first husband who had died when she was a baby. She had much of her mother’s brisk manner and angular features wholly her own and thought to be too sharp and too forceful for beauty.

“Oh, so ‘tis,” Vati looked around him vaguely. He stood a head shorter than his stepdaughter, a gnome-like and lightly-built little man of middle age, whose near-sighted gray eyes reflected both the gentle wisdom of years but still some of the innocent enthusiasm of a child. “I lose track of the days, in the shop and away from the land. And that is the problem, dear Magda. There is barely enough to support us now. How will you all live, when my share is divided between the boys and you have a dower-share as did Liesel when she married Hansi?”

“I don’t care to marry,” Magda answered with a toss of her head. “I don’t care in the slightest for any of the eligible bachelors in Albeck, and I don’t want to go elsewhere. Who would look after you and Mutti?”

“Even so. But you still should marry, my dear child. It would make your mother so happy,” Vati said and looked at her very searchingly. “Don’t you wish for it, in the least?”

“I don’t know what I really want, Vati,” Magda answered. “I would like a husband that I could talk to, as I talk to you. Someone who is kind, and amusing; if I could find someone just like you or like Uncle Simon, I think I would marry very happily. But there is no one else like you in Albeck!”

“Alas, I am sui generis,” Vati agreed somewhat smugly as they walked towards the gate that led into the Steinmetz holding, where a lantern burned primrose in the twilight of the cobbled yard and the range of fine timber and stone buildings surrounding it. “But still, my dear child, you should be caring for your own husband and children,” he chided her, fondly. “Now, you see, there would be another reason for going to Texas. Besides three hundred and twenty acres of land— good rich land it is—for each family, there would be a chance for you to find a husband that would better suit you than a dull old farmer with his head among the cabbages. Some splendid young Leatherstocking hero or a bold Indian chief; would that content you, Magda?”

He looked teasingly sideways at her and thought she blushed slightly, even as she laughed and answered, “But it would mean going away from here, Vati—from everything.”

The older man and the young woman paused in the gateway as if both of them had a single thought. This was the house where all of Friedrich Christian Steinmetz’s ancestors had lived, where they had stabled their horses and cattle and gone out to tend their fields and pastures. Not an inch of it had known any but their hands for hundreds of years. Vati’s, or any one of the previous Steinmetzes’ hands alone had piled hay in the loft, repaired the tiled roofs of the barn, house, or chicken house, boiled cattle-feed in the great iron kettle. Their wives had borne the next generation in the great bedroom upstairs, and their children had run out to chase chickens in the yard. Here were their roots set, generations deep. Although Magda was not truly one of them by blood, she had still lived here for nearly all of her life as Vati’s much-loved oldest daughter.

“So it would,” and Vati’s eyes looked grave behind his glasses, as he opened the door into the farmhouse kitchen. “We could hardly take it all with us.” They stepped into the little entry and from there into the warmth of the kitchen, scoured as clean as a new pin, full of the smell of food cooking and the yeasty scent of bread on the rise.

“Christian, my heart, my hands are all over flour!” exclaimed Magda’s mother from beside the trough of dough. “You are early.” Hannah Vogel Steinmetz did not look like either of her daughters: she was a plump little wren of a woman, brown-haired and rosy. Vati kissed her on the lips with a good enthusiastic smack before he was swarmed by his sons, Friedrich, and Johann and granddaughter Anna, with joyous shouts of “Vati! Opa!” and a treble chorus of questions and accounts of what had been going on over the last few days.

The boys were twins of the age of seven, as alike as two peas for looks, having Vati’s grey eyes and Mutti’s fair to light brown hair, but very different in nature. Johann was serious and shy, Friedrich a daring scamp. It baffled Magda when people claimed they couldn’t tell the boys apart. Friedrich’s face was rounder, and he was the outgoing, happy-go-lucky adventurer. Johann’s face was thinner; he was the more timid and serious one. Magda didn’t think much of people who didn’t notice those elemental differences. Weren’t they looking closely enough; how could they not see something so simple?

Anna had serious dark brown eyes like her father, Hansi Richter, her mother Liesel’s dimples and brown curls too short and wispy to be woven into plaits. A solemn-faced little mite, she could on occasion be brought to laugh, a happy little trilling sound almost like a bird. The younger children addressed Magda as ‘Auntie Magda’, since she was so very much older than they. Now Magda set Vati’s box of tools in the cupboard by the door and put the emigrant pamphlet into the pocket of her apron, for later.

“Children!” Hannah chided them. “Boys, you must behave!”

“No they must not—they are only children,” Vati answered indulgently and swept small Anna up in his arms, whereupon a look of comic distress crossed his face. “Oh, dear, she has had a small accident …”

“Liesel!” Hannah exclaimed, and Liesel, Magda’s half-sister, answered crossly from a chair by the fire:

“I’m nursing the baby, Mutti, I’ll see to Anna when I can!”

“I’ll do it, Lise,” Magda said, taking her small niece into her arms, and Liesel said distractedly:

“Oh, of course you will!”

Magda and her parents exchanged a meaningful look, as Hannah murmured, “New mothers’ nerves.”

Magda shrugged and took Anna. Liesel was still in one of her black moods. She had always been that way, even before marrying Hansi and bearing her children. Vati had once observed, “Annaliese is either on top of the tallest tower or in the cellar—nothing in between!” When Hansi had been making fumbling attempts to court Magda—to Magda’s hideous embarrassment, for Hansi had been her childhood playfellow, more like a brother than a suitor—Liesel had been serenely confident that he would be hers some day. She had adored Hansi since she was a tiny girl; Hansi—patient, stubborn and reliable with dark brown eyes so like one of his own oxen.

“He is only courting you out of courtesy, because you are the oldest,” she said then.

Magda retorted waspishly, “And Vati will dower me with the small field adjacent to his! I can’t help thinking that is my most attractive feature in his eyes!” She could look in Mutti’s little silver hand-mirror and acknowledge that she was dark and over-tall, while her sister was dainty and fair and everything considered beautiful. And Liesel had giggled, while Magda added, “He is just like all the other marriageable men in Albeck; he fumbles for words when he talks to me but his eyes follow you like a hungry dog!”

“Well, once he brings himself to speak of marriage,” Liesel consoled her, “you may slap his nose and say of course not—and then he will come to me and I will console him. And you both will sigh with relief and Hansi and I will live happily ever after and have lots of children, and you will marry a prince or a schoolmaster and come to visit us, riding in a grand barouche with footmen riding behind. You will live in a castle full of books . . .” She went on elaborating their fortunes until Magda had begun to laugh as well, for that was Liesel in her tallest-tower mood; merry and affectionate, and absolutely certain of Hansi’s eventual affections. And so it had come to pass; Liesel’s dark-cellar moods over the three years since had been infrequent. The worst one came after Anna’s birth, and then again after Joachim, the baby. Magda supposed that the brunt of them now fell on Hansi, but he seemed well able to cope.

Now everyone, especially Magda put it out of their minds that he had ever courted her. Not an easy thing to do, when they all lived in the same house. But it was made easier by the fact that Hansi never talked of much beyond crops and his manure-pile. All very well because such matters put food on the table for them all, but Magda privately thought she would shortly have gone mad from a lifetime of sharing Hansi’s conversation about them. She would rather go on living as a spinster under Mutti’s authority and talk with Vati about his books and notions than endure more of it than she did already. Now this talk of Adelsverein and Texas made her uneasy, as if something whispered in the corner, something from one of Vati’s old tales that always gave her the shivers. She took Anna into the other room to change her sopping-wet diaper, and when they returned, Hansi himself had just come in from the barn.

“I think to start spreading the muck, as soon as the weather lets up,” he was saying conversationally. Magda reminded herself yet again that he made Liesel happy and worked Vati’s fields for him, and that’s what counted.

After supper, she closeted herself in the little room at the end of the upper floor, the little room she had to herself since Liesel married. She lit a tallow candle and began to read. When she was finished reading it was late, but there was still someone downstairs in the big kitchen, where firelight still gleamed warmly over the polished copper pots and pans and on the row of pottery jugs hanging above the fire.

Vati sat with his scrap album on his lap, in the chair where Liesel sat to nurse the baby, leafing over pages neatly filled with carefully-cut news sheet articles. He looked up at Magda.

“Well? What did you think?” The firelight gleamed on his spectacles, like the eyes of some large insect.

“It’s almost too good to be true,” she answered thoughtfully. “They offer so much. I wonder what they are to get out of it.”

“A colony, land, hard workers.” Vati took off his glasses and polished them absently on his shirt sleeve, and Magda sat down on the bench opposite him.

“The Firsts have all that of the common folk, now,” Magda pointed out, sardonically. “Hard-working tenants who take off their hats when one of them walks by. Would they expect that of us, in Texas, then? Might this be some clever means of skinning those who have managed to put a little money aside? All the gold should flow uphill, into the Firsts’ money-bags, as they so kindly relieve us of the heavy responsibility of deciding what we should do with what we earn. They have so many better notions of what to do with it, after all.”

“Such a cynic, my Magda!” Vati chided her.

She answered bitterly, “Such as you have made me, by allowing me to read your books and newspapers, and talking to me of important matters.”

“Maybe they look for the honor of doing a good deed for the people. They are very forward thinking gentlemen, all of them.”

“Perhaps; they are all but men and capable of shabby deeds as well as the noble.” Magda became aware that her stepfather was staring thoughtfully into the fire, his expression very serious. “Vati, what is it? What is it that you know that you have not told us?”

Vati tore his gaze away from contemplation of the fire and looked gravely at her.

“It might be well to think about leaving, Magda my heart, and soon, while we can still afford it. All of us; Liesel and Hansi, and the children. There is talk in the air—oh, there has always been such, but this is new talk, talk such as I remember when I was a boy and the Emperor Napoleon was on the march. Talk of conscription and war and repressions. I do not like it—not for myself, you understand. There is no one’s army would want a decrepit old clockmaker! But the boys—yes, they would want Friedrich and Johann in a few years, if it came to pass, and I won’t have it. There is also the fact that business has not been good. So many factories, so much mechanization of things, so much change! And they will change, whether we wish to change or not. There will be new rules and repression of so-called dangerous thoughts brought down upon those of us who dare to think about such matters! What to do, Magda, what to do!”

“It is advised to take all that you can in a cart and sell the beasts that pull it at the port,” Hansi answered decisively from the other end of the room. Startled, Magda and Vati looked up. Liesel’s husband stood in the doorway for a moment, with Anna in his arms, half asleep. “And take apart the cart, and ship it with all your goods, since a good one may be hard to come by in the wilderness.”

Magda regarded her brother-in-law with considerable surprise: How long had Hansi been thinking the same things as Vati? He strode across the room and sat himself down on the bench next to Magda, settling Anna in his lap so that she curled up, sucking her thumb.

“Anna couldn’t sleep, and Liesel was nursing the little one,” he added half-defensively, but he looked levelly at the two of them, all diffidence and talk of the muck pile set aside. “I heard you talking, so I came downstairs.”

They looked at each other for a long moment, before Vati finally asked, “How long have you been thinking about emigration, Hansi?”

“A while,” he answered readily, and there was firmness in his voice, and in his answer to Vati that Magda had never thought to see in Hansi. He wasn’t impulsive; there was no dash to him. In a thousand years he would never do anything that his neighbors and family hadn’t already done before, but there it was. He had been thinking long and seriously about emigration for that was the way Hansi did things.

“Go with us to Texas.” Hansi savored the words, much as Vati had, and continued, “Everyone is talking about it in Albeck these last few weeks. I thought about going myself, first before we married. Then I thought about the two of us going together, and then Anna was born and then the new baby. You are right, Vati. We should go now, while we still can.”

“What about the fields?” Magda asked, the fields that he cared about to the exclusion of practically anything else, and Hansi shook his head, regretfully.

“It hurts me to say, but here is the truth of it. There’s not enough. Not to grow enough hay for winter, not enough to grow what we need of beets or wheat or potatoes. There’s just not enough, for all I break my back working at it and no way to get any more. The Adelsverein promises to send us all there, give us a house, everything we’ll need for the first year—and three hundred and twenty acres.” Hansi’s face lit up in rapture as he said those last words. “Think of what I could do with that much good rich land. It’s as much as all the fields around Albeck, almost.”

Looking at the faces of Vati and her brother-in-law, Magda felt a chill around her heart, for it seemed to her that they were already decided, their feet all but set on that road.

Annaliese Richter was still awake when Hansi quietly returned upstairs with his slumbering daughter in his arms. Liesel watched him through her eyelashes, savoring the very look of him, a solid square man, perhaps a little shorter than most, but a very rock for dependability. He moved quietly around the room, tenderly putting Anna in the truckle-bed at the foot of theirs and settling the covers around the child. She closed her eyes as he leaned over the baby’s cradle, drawn close to her side of the bed. It was her secret pleasure to watch her husband when he didn’t know that her eyes were on him. She never doubted that he would marry her, for she had adored him since she was a little girl in short skirts herself and he was a stocky boy more than a little taken with her clever older sister; Hansi, stout and stubborn and good with cattle. Steady and reliable, funny in a mild way when he felt like it.

It had always been a mystery for Liesel why her sister did not see or value those qualities in Hansi. Why had Magda not loved him? Magda with her head in books, Vati’s favorite daughter, such a mystery! But exactly as Liesel had known would happen, Magda had come to her sister saying impatiently:

‘That blockhead of a boy asked me if I would marry him! I told him not to be ridiculous, and to ask you instead! You worship the ground he walks on, anyway. Don’t be a ninny—say yes to him, so he’ll stop pestering me!’

Liesel did not mind at all that Magda had left him to her. It only proved that books did not tell you everything. Oh, no—books did not tell you anything about certain pleasures of marriage, certain things that she was privy to now, as a married woman. Magda did not know about that, for it was not a thing that an unmarried girl should know about; it wasn’t proper. But she did, Liesel thought—there were things she knew that her clever sister didn’t! She listened to the soft sounds of her husband undressing and climbing into bed to settle himself at her back. Her heart warmed with renewed affection; he took such tender care, quietly returning to bed without disturbing her, after seeing to Anna! Liesel knew that many husbands wouldn’t have bothered. Tending the children was the business of their mothers, no matter how exhausted from nursing a fretful baby or the work of the farm. Many another man acted as if once their wives had spread their legs apart for them, that was all they needed to do in regards to their children. But Hansi wasn’t like that, not a bit of it. In his own quiet way, he took as much an interest in Anna and baby Joachim as Vati took in his own children. And for that, Liesel loved him all the more, if that were possible. She turned in the bed, reaching out as if half-slumbering, asking drowsily, “Are you just now coming to bed, Hansi? Whatever were you talking about for so long?”

He did not answer at once, but his arm curled around her. At last he answered, “We talked about going to Texas, Lise.”

All thought of sleep was banished as if Liesel had been doused with a bucket of ice-cold water. She found her voice at last.

“And what did you say on that, hearts-love?”

He took a long time in answering, for he was a careful and considerate man.

“We ought to not let such an opportunity pass, Lise. We should go.”

Liesel Richter did not sleep well that night, for those words echoing in her troubled dreams.

We ought not to let such an opportunity pass . . . we should go.

In the morning, she did as she had done all her life—she asked her sister what she thought, as they milked the cows in the morning darkness in the barn.

“What did you and Vati talk to him about last night?” she asked, leaning her cheek against the warm flank of a cow as her hands rhythmically squeezed spurts of milk into a pail. Magda was similarly occupied. “The baby kept me awake. When he came to bed, he said you were talking about going to Texas. I thought he was joking with me, Magda. He can’t be serious!”

“Hansi never jokes,” Magda answered, somberly. “He is serious, and Vati, too.”

“What do you think of it?” Liesel asked after some moments of anxious silence broken only by the quiet hissing of milk breaking the surface in their pails. Magda was clever; Vati’s daughter of the soul, if Liesel was his in blood. She always knew what to do.

“It might be rather interesting,” Magda ventured at last, and Liesel’s heart sank. “They promise us a new house. I expect it will be rather like the one in Herr Sealsfields’ Cabin Book, in a wild and beautiful garden. Think on it, Lise—a house of your own!”

“But to leave here!” Liesel’s voice trembled. How could they think to leave Albeck, everything they had ever known? “To leave everything behind and just go! I can’t bear the thought of taking the children all across that ocean, going out to the wilderness! I really can’t! How can he even consider such a thing, Magda?”

“Nonetheless, he is, and Vati also,” Magda replied, blunt and practical. “And he is your husband, Lise. If he says that he wishes it, you must obey . . . just as Mutti and I must obey Vati.”

No. This was horrible. Vati could contemplate such a thing; he was a willow-the-wisp for enthusiasms, a man of books and the tiny gears of clocks spread across his workbench. Not Hansi, who never had a thought which had not already occurred to his ancestors.

“But you have Vati twisted around your finger,” Liesel pleaded, already knowing that she protested fruitlessly against the inevitable. “He would not make you go if you did not wish it.”

“But Vati does wish to take the Verein’s offer,” Magda sighed, from the other side of the cow. “He has already convinced himself that it would be for the best for us. He reads books and talks to people, Vati does. He sees that things are not good and growing worse.” As Liesel watched, her sister deftly squeezed out the last rich drops of milk from the cow’s udder. She stroked the creature’s flank with brisk affection before moving her milk-stool and herself on to the next cow. She looked sympathetically at Liesel as she did so. “Lise . . . dear little sister, I think our father made up his mind long since. He just waited upon the opportunity, and now the Adelsverein have given it to him. He and Hansi will sign the contracts, no matter what you and Mutti will have to say about it.”

“Oh, and Mutti will have plenty to say,” Liesel predicted with gloomy relish, hoping against hope as she did so that perhaps Mutti might prevail against this insanity. “And she will weep tears by the bucket!”

“To no effect,” Magda answered. “In their hearts, Hansi and Vati are already there, running their hands through rich soil and counting ownership of more land than either of them ever dreamed.”

“What shall we do then?” Liesel asked. Her sister turned her head and smiled at her.

“Think on those things which we value the most, and contrive some means of taking them with us,” she answered. “Tears will avail us nothing, Lise. Smile and be brave.”

On the day of their leaving, a bright and clear September day, Mutti cried as if her heart were breaking in two. There was a small gathering in the farmyard, clustering around the Steinmetzs’ and the Richters’ carts: Hansi’s older brothers Joachim and Jurgen and his parents, Mutti’s friends and a scattering of younger women, Liesel and Magda’s contemporaries. Auntie Ursula, the sister of Mutti’s first husband and her husband Onkel Oscar had come out from where they lived in Ulm on this momentous day. There were not too many other men, for it was harvest-time and most had already gone out to their fields. It felt very strange to Magda for them not to be at work themselves, not to be gathering their own harvest, filling the storerooms and larder in the old house. It was as if they were already strangers.

At the moment when they had finished taking the last of their things from the house, Vati’s friend from Ulm, Simon the goldsmith, came rushing into the yard with a small package in his arms.

“I was afraid I would be too late!” he gasped, as he and Vati embraced. “This is for you,” he added, thrusting the package at Vati. “A quire of fine letter paper and ink and pens enough for two or three scriveners, all to encourage you to write to me, as often as you can. I shall want to know every detail of your venture, Christian!” And he beamed at Vati, while Vati thanked him effusively.

“My people are given to travel widely,” Simon gracefully waved off the thanks. “But so far, I know few who have ventured into Texas! I will look forward to your letters with great interest.” Simon smiled warmly at Magda, the skin crinkling around his wise old eyes, and added, “You must remind him to write, Miss Margaretha, since we both know how forgetful your father may be. I shall miss his company very much; letters will be a poor substitute.”

“I won’t forget, Uncle Simon,” Magda answered. He smiled again, but did not embrace her as he did her father. Such was not the custom among his people, for a man to touch a woman not his wife for all that Simon and her father were so close, close enough that they all called him their uncle.

“Good!” Simon looked at their carts, laden with all but the last few little things. “I see you took my advice about traveling with only the essentials. And all your papers are in order?”

“I have them right here.” Vati patted the leather wallet, tucked into the inner pocket of his coat. It held all the necessary permits, visas and certificates; everything that the Verein had requested of Vati and Hansi to have in order before signing their contracts. “Don’t worry, Simon—Magda shall see that I keep them safe. We arranged the sale of everything that is not in the carts,” Vati added cheerily. Perhaps that was why Mutti wept in the arms of her dearest friend, Auntie Ursula, now that the moment had come to leave behind everything that had made her home so comfortable and welcoming. Vati continued, “We expect to live like gypsies, at least until we get to our new homes in Texas. Did I tell you they had assured us each a house, built on our own lands? It will probably not be as solid as what we leave behind, but I expect we shall prosper, none the less.” Certainly that was what Hansi expected. Even if Liesel seemed as apprehensive as Mutti about leaving, she always believed what Hansi said.

“If you have any need of help once you reach Bremen,” added Simon, his eyes beginning to overflow, “call upon my cousin David. I have written to him already. A safe journey for you, a safe journey and a golden future, my friend!”

“To be sure,” Vati answered happily, as he wrung Simon’s hand again and consulted his pocket-watch. “It is time, my dears. Now let our adventure begin with a smile, Hannah-my-heart . . . Magda, boys . . . ” He deftly detached Mutti from Auntie Ursula with many determinedly cheerful words and handed her up into the first laden cart, where she sat with her shawl pulled tight around her elbows and her cheeks wet with tears. She reached down to grasp Auntie Ursula’s hand while both wept mournfully.

“. . . so far away,” Auntie Ursula choked out, through her sobs, “Such fearful dangers, robbers and brigands! We will never see you and the children again!”

“Of course you will see us again,” Magda said roundly although she did not believe it herself. She picked up her skirts and scrambled up to sit next to Mutti. She worried that Mutti and Aunt Ursula’s tears might frighten the children, especially Anna. They were leaving the only place they knew, bound to be frightening enough for them, especially if Mutti carried on too long about it. She put her arm around her mother’s shoulders. The horses shifted restlessly in harness, and the twins drummed their heels on the sides of the wooden chests upon which they sat, until Magda turned and told them to stop.

“Are we leaving now, Auntie Magda?” asked Friedrich, excitedly.

Magda answered, “As soon as Vati is finished talking to Uncle Simon, Fredi.” On the other cart, Liesel had the baby in her lap. Anna sat prim and wide-eyed beside her. The moment had come. Hansi’s brother Jurgen slapped his shoulder, and his mother hugged him to her one last time, ruffling his hair as if he were still a small boy.

“Go with us to Texas,” he said jauntily. “I’ll write and let you know when it’s safe, Jurgen,” and his brother Jurgen jeered half-enviously, as Hansi climbed up and picked up the reins of his team.

“Away with you,” Jurgen called cheerfully after Hansi’s cart, as it creaked slowly towards the gateway and the road beyond, “and have a care for the wild Indians!”

Vati embraced Simon one last time, clambered spryly into the cart, where there was just enough room for the three of them, and chirruped to the horses. Auntie Ursula walked beside it, still holding onto Mutti’s hand and both of them sobbing uncontrollably until they reached the gate and passed out into the road with a lurch and a bump.

“Goodbye, goodbye!” the boys shrilled from the top of the pile of boxes and chests lashed to the cart, “Goodbye! We’re off to Texas! Here we go, we’re away to Texas!”

Magda silently handed a handkerchief to her mother. They squeezed elbow to elbow on the narrow seat. Hannah dabbed her streaming eyes with the handkerchief and blew her nose. Vati looked across at her and smiled, as happily as his sons, saying, “The open road calls us, Hannah-my-heart. Can’t you hear it?”

“Nonsense,” Mutti snorted. “All I hear is Peter Frimmel cursing because he has stacked the hay too tall and it has fallen off onto the road.”

They passed the last buildings of Albeck, dreaming under a deep blue autumn sky. Out among the meadows, and golden fields of wheat and barley still bowed heavy-laden and unharvested, or lay in neatly mown stubble. One or two of their neighbors, already hard at work, waved cheerfully as Hansi and then Vati’s carts passed by on the little road that led to the bigger road that would take them towards Wurzburg and the north, to Bremen on the sea where waited the ship that would take them away. At a turning in the road, Hansi’s cart halted, and Vati said, “What can be the matter already; did one of the horses lose a shoe?”

But ahead of them, Hansi was standing and lifting Anna in his arms.

“Look,” he called to them all, “look back, for that is the last sight of Albeck! Look well, and remember—for that is the very last that we will see of our old home!”

Magda’s breath caught in her throat. She turned in the seat, as Hansi said and looked back at the huddle of roofs around the church spire, like a little ship afloat in a sea of golden fields. All they knew, all that was dear and familiar lay small in the distance behind their two laden carts. Really, she would slap Hansi if that started Mutti crying again. Even Vati looked sobered; once around the bend of the road, trees would hide Albeck from their sight, as if it had never been a part of them, or they a part of it.

Magda lifted her chin bravely and said to Vati, “Really, I wonder how suddenly Hansi got to be so sentimental. We should drive on, Vati. There’s no good in dragging our feet like this. Texas may wait for us, but the Verein ship won’t.”

“Right you are, dearest child.” Vati slapped the reins, and the horses moved on again. Only Mutti looked back, her face wet again with fresh tears. Many years later, Magda would wonder if that were an omen.

* * *

From The Sowing: Chapter Five – The Cold Wind of Secession

“We were there for the wedding of Margaret’s son to Miss Amelia Stoddard,” Oma Magda said, “in March of the year that the war began. Her father was a wealthy man and she his favorite child. The groom had volunteered for the new State Army. Everyone wished that they be married before he was called away with his friends.”

“Was it a splendid wedding, Oma?” asked Marie, although her brothers hooted scornfully at such a girlish interest.

Oma Magda smiled and answered, “It was. Our little Hannah was included as one of her attendants, at the last minute. It was Margaret’s doing, of course. I had never seen such a mansion as Mayfield until then; like a palace, in a grove of trees and a garden all around. Miss Amelia was married in the grand front hall. She came down the stairs, floating as if she were an angel. She looked so very happy. Everyone remarked on it, of course, even my husband.”

That was not exactly what he had said, though, as she leaned on his arm. They stood with Doctor Williamson and Margaret, who was a splendid vision in burgundy-and-white striped faille—in the front rank of guests as suited their position as the family of the groom. The younger Vining boys waited at the foot of the staircase with Horace.

“I hope they are not teasing him too much,” Margaret said. “He had a nervous stomach as a child. So mortifying to be sick in front of everyone!”

“Surely not,” answered her husband with calm detachment. Doctor Williamson looked around in mild puzzlement, as if wondering what on earth he was doing at Mayfield, in its two-storied hall with the graceful wood staircase curving like a nautilus shell down from the gallery above. “And if he is, I left my bag in the brake. I am sure I can administer some curative tonic.”

“She looks so beautiful,” Magda whispered in German.

Her husband whispered back in wry amusement, “At least she doesn’t look as if her mother and sisters have just finished frightening the very daylights out of her about what happens tonight!”

“Shush!” whispered Margaret.

Magda returned indignantly, “I did not have the daylights frightened out of me!”

“You did, too,” Carl murmured into her ear so only she could hear, as his sister gave him an especially severe look of disapproval. “You looked for all the world as if you were about to run screaming. I could have wrung Liesel’s neck.” He covered her hand with his, the hand with Mutti’s heavy gold ring on it. Magda thought back to her own wedding day: tightly laced into a borrowed dress, herded into the church like a stray heifer, trembling on the thin edge of panic. But it had turned out well, for he had been kind. She hoped that young Horace would be kind and that he would have many days and nights with the girl Amelia, who was now floating downstairs in a cloud of whispering white silk and orange blossoms.

She hoped also that they would be happy together ever afterwards, as it was in all the old stories. Even if they all were now living under the shadow of war, as the confederacy of states seceding from the Union lined up, eager for the chance to aggressively defend their rights. Even if no one could quite agree on what those rights might be, even if one of the rights insisted upon—in the harshest terms imaginable—was the right to hold other human beings in cruel bondage.

Horace, young Peter and his brothers, young Stoddard who had talked so boldly at Margaret’s dinner table, and her husband’s old comrade, Colonel Ford; they all were prepared to ride away into war, perhaps tomorrow, while Margaret stoically basted together grey uniform tunics and Magda’s own husband feared for them all in the deepest recess of his heart.

But for a while at least it seemed as if Margaret and the Stoddards were wishing away that black cloud, almost through a force of will, as the vows were spoken and Amelia and Horace were pronounced man and wife. The invited guests gathered close to congratulate them, while Negro servants brought around trays of glasses full of champagne for the toasts. Peter and his brothers drifted away towards their friends, trailed by Dolph and Sam. The bride stood with her new husband, her maids around her, like a bright flower-bed, as Mr. Stoddard stood on the lower steps of the staircase to call out toasts to young Horace and his daughter and to their loving families. Everyone drank to them, drank deep and with joy and hearty good wishes.

“Here’s to the Confederacy!” Mr. Stoddard called out, to a great and lusty cheer from all the company. At first Magda thought that all drank from their glasses, although she barely touched the glass to her lips, as did Margaret. Her husband ostentatiously did not lift his glass at all, a quiet and cold expression on his face that dared anyone to make something of it. People near them were already whispering, their disapproval and hostility almost palpable. Magda’s heart quailed within her. Mr. Stoddard scowled, his countenance already flushing red as a beet as he glowered at Carl. Her husband did not seem to care; he held the delicate glass in his hand, his head lifted proudly. This far and not an inch farther, he seemed to say with every fiber of his being. Magda was reminded of an etching in one of Vati’s books, of Martin Luther defying the Council of Worms—Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. Neither would her husband go against his conscience. Not for the affection that he held for old comrades, not for love of his sister and nephews, not even for something as trivial as a wedding toast. There were many hard looks sent in his direction then, especially from the young men already in militia grey; but also from their elders, the men in fine coats. And then one of them stepped forward, a lanky man with fading red hair—Colonel Ford, in his grey uniform coat all sewn with gold braid, a sword-belt buckled over a fringed silk sash at his waist.

“A toast!” he cried. “To Texas, and all those true sons who fight for her!”

The roar of acclamation crashed in Mayfield’s hall like the sound of the surf. At that, her husband’s reserve seemed to break.

He drank deep and when he lowered his glass he looked around, observing mildly, “I’d throw the glass into the fireplace, if you had such in the hall and the glasses weren’t so rare, Stoddard. That’s a toast such as that none other ought to be drunk out of them.”

“None should know better than one of Jack Hays’s comrades!” Colonel Ford answered fervently. From the murmur of approbation, the bad moment looked to have passed them by. Magda considered how and what she might say to Colonel Ford in thanks. It seemed to her that he had come to her husband’s rescue at just the right moment. Many of the company were still looking at them, with such contemptuous disapproval in their regard!

Margaret appeared to rise cheerfully above the scene of the unfortunate toast, saying only, “Mr. Stoddard sent for the champagne all the way to France. At great expense, I might add . . . although it is hard to see why.”

“Indeed,” Carl looked into his glass, now near-empty after that last toast. “I think I’d rather have some of Charley Nimitz’s beer instead.”

“Oh, hush,” Margaret said, turning to embrace Mrs. Stoddard. “Oh, my dear, it was lovely! She looks like an angel. This is my brother and his wife—you remember, they were at dinner the other night?”

“Of course.” It seemed to Magda that Mrs. Stoddard would have been very chill if Margaret had not been there. As it was, she murmured a dutiful welcome and rustled away like an enormous animated peony.

Margaret maintained her usual serene face and said, “The house is so very grand—in the very latest taste, of course. Mr. Stoddard made his money in Brazoria, growing rice and cotton . . . and in trading.” Magda noticed that she did not say what commodity Mr. Stoddard traded in and rather thought that she could guess. That must have been what Margaret meant when she had said something about not approving of slavery, but the practice being so common among one’s friends. Margaret continued, “But I’m afraid unless you have a lot of guests, everyone rattles around like a pea in a gourd.”

She kept Magda and her brother close to her side. Magda had thought at first that Margaret was sheltering herself from the gentle malice of the other female guests, the family and close friends of the Stoddards. She was only the country relation, the wife of a plain farmer, in an unfashionably dark dress, ameliorated at the last minute by addition of a new lace collar which Margaret had pressed upon her. From the way that young Mr. Stoddard and the other young sparks were scowling at them, Magda realized rather that it was her husband that Margaret protected from social isolation, or worse, in this elegant company. Margaret and the Doctor, as parents of the bridegroom, could not be so easily snubbed, as Carl and Magda would have been if they were there alone. She resolved to follow Margaret’s serenely gracious lead, but wondered how long this would drag on.

“I feel like the goose girl, invited to the palace.” she ventured at last.

Margaret laughed softly. “I know! The truth is I do not envy the Stoddards for their house at all. I am always more than happy to go home and sit in my cozy parlor.”

“Looks more like a temple, from the front, than a house,” Doctor Williamson commented. “Why a Greek temple, transplanted to Texas? I’ve always wondered about that.”

“It’s no more out of place than a Gothic church,” Carl pointed out.

Margaret added, “Really, if you go by what was here to start with, we’d all be living in skin lodges,” and they all laughed from the very absurdity of such a picture.

Doctor Williamson tugged at his tall collar and neck cloth. “We would not have to dress up to quite this degree, if such were the case.”

“Stop that,” Margaret ordered and reaching up straightened her husband’s collar dexterously.

Carl began to laugh. “It reminds me of a party that the good folk of Bexar put on to honor Jack, back when we first began patrolling the countryside. The Comanche raided pretty close back then, you know. It wasn’t safe for farmers to plow in their own fields, even if it were just a stone’s throw from town. Well, we put a stop to that.”

“I imagine they were most grateful,” Doctor Williamson ventured.

Carl nodded. “They were, so they resolved to invite Jack and two of his officers to a grand ball. Jack said that if he were going to suffer through it that he wasn’t going to suffer alone, so he detailed Mike Chevallier and me to come with him. There was only one problem.” He grinned, reminiscently. “We were poor young sparks, with hardly two bits to rub together and very little thought about attending such formal doings. The whole company had only one good coat among all of us.”

“What did you do, then?” Margaret asked.

Her brother laughed outright. “Well, Jack put on the coat and made an entrance into the assembly, but as soon as he could, he slipped out the back way, and took off the coat and gave it to Mike, who went in to be greeted by all. Then he came out and gave the coat to me and I did the same. That coat saw more of the party than any of us did.”

“It sounds like a theatrical farce,” Margaret said, laughing. “And how long did you keep that going, little brother?”

“Three or four times, I think. It was a very merry company. It took some time for anyone to notice that only one of us was there at any particular moment and that the coat fit all of us very badly.”

“And then what did you do?” asked the Doctor.

Carl answered, “Oh, the party had advanced very well by that time; we all came in, and confessed up. Everyone was very amused— but it didn’t increase our pay.” He looked across the hall, at the moving crowd of guests—the women in their graceful, bell-shaped crinolines and at the men, so many of them already in grey tunics trimmed with braid—and added irreverently, “Somehow, I don’t think many of them are slipping out the back and sharing their coats!”

“We shall have to slip out ourselves, presently,” Margaret pointed out. “We must be there to welcome the bridal procession and there are many more guests who are coming to the reception.” Margaret signaled to one of the hovering servants, who collected their empty glasses and agreed readily to take a message for Daddy Hurst to bring the brake around. “Peter will see to the boys,” she said, “and Hannah will ride in the open carriage with Amelia and Horace. Do not worry about your little chick, Magda. I have already told her what to expect and Amelia said she will let her carry her bouquet during the drive to our house.”

They took their leave of the Stoddard’s magnificent house, with no small relief. Margaret had Daddy Hurst take the shortest way possible returning to her house. “They will be some time, with the other horses and carriages,” she predicted. “And I myself would like to catch my breath before the deluge of guests.”

“Just who have you invited, my dear?” asked Doctor Williamson in some alarm, appearing to have heard of this now for the very first time.

“Oh, everyone!” answered Margaret comfortably. “But not to worry, my dear. If you wish, you can wander off to your study with a book. Everyone will think you are in another room. The one advantage,” she added to Magda and Carl, “of a large house with many little rooms.”

Margaret’s little rest, though, took no longer than she needed to remove bonnet and mantle and pin a lacy white house cap over her hair. “I must see that the girls have put out the tables properly,” she said, “and I had arranged to borrow plates and silver from Mrs. Edwards’ establishment, and they have not arrived . . .”

“I thought I worked hard,” Magda confessed, as Margaret’s footsteps tap-tap-tapped down the hallway from the family parlor, “but she makes me exhausted, just to follow after her. I cannot imagine how she does it!”

“I’ve often considered,” Carl agreed, “that the world would be in a much better state if the Almighty had just put Margaret in charge of it from the start!”

In accordance with her plan, they did have a little time before the procession of carriages bearing the wedding party, and the bride’s parents and friends came up the gravel drive between the blooming apple trees. Time for Daddy Hurst to arrive with two hampers of plates and glasses and a plump lady breathless with apologies for having forgotten the very day, for her establishment was all upset with sending her daughter and the children off to rejoin her son-in- law. He was an officer in the Army, the plump lady explained to Magda and he had been paroled back East, and her daughter wouldn’t listen to a word but that she had resolved to go to him, and the dreadful danger she and the babies would be in, wasn’t it just dreadful! Magda lost the rest of the story between the rapidity of the plump lady’s English and Margaret’s urgent plea for help with rearranging the table in the verandah with the wedding cake displayed upon it.

Thereafter, Magda followed gamely in Margaret’s magnificent burgundy and white faille wake, as the latter attended to the arriving torrent of guests and the demands of bountiful hospitality, spread throughout the many rooms and deep verandahs of the Becker home place. She did catch a glimpse through an opened French door of her husband and some other men—dear God in heaven, they were not having words? The other men looked angry, and her husband had that cold, tense look to his face that she had seen only a few times before. But as she watched from inside the room, he turned on his heel and strode away, ignoring the other men. One of them shouted something after him, something she couldn’t hear for the clamor of guests.

At that moment, one of the hired girls dropped a tray of dirty plates with an almighty crash. When she looked back again, the men were gone. She went to look for Carl and saw him sitting in one of the chairs on the verandah outside Margaret’s little parlor, with an older gentleman who had a handsome craggy face and a mane of hair like an old lion. She had noticed him before, more because he also seemed to be another outsider. Well, she thought, at least Carl did have someone to talk to; another old friend like Colonel Ford, to judge by the look of them, at ease together.

“They seem to be giving you the cold shoulder as well,” Carl remarked. He held up the bottle. “I know you don’t. You mind if I do?”

The older man shook his head, “Not at all. Houston does not spree. Miss Maggy Lea put an end to that long ago, but I have no objection to others doing so.” There was a deep glint of mischief in the old man’s eyes as he added, “Mrs. Williamson would doubtless have a quiet word in her ear, if it proved otherwise. Houston wins no arguments with women named Margaret.”

“Funny how that works out, doesn’t it?” Carl poured himself a couple of fingers. “I don’t win many, either, and I’ve tried since I was in small-clothes. She’s my sister. Mrs. Williamson, that is. M’name’s Becker.”

“Ah.” Sam Houston leaned back in his own chair, with a look of satisfaction. “Thought I knew you. Your father came to join us in those desperate days in ‘36, I recall. A scout with my dear friend, Captain Smith. A tall, fair-haired man—you have the very look of him, I vow. He scouted for us, and took a place in the line at San Jacinto. You did something of that rangering yourself later on, did you not?”

Carl nodded. “With Smith’s company and then with Jack Hays.”

The old man sighed and offered, “Not a likely man to accuse of cowardice, then. In my young days, I’d have called him out for that insult.”

“He was young and reckless,” Carl answered only, “and I didn’t want to spoil my sister’s party. Seemed a waste to kill him, really, considering the mess and the embarrassment to my sister.”

“You’d only be depriving some Yankee of the privilege, down the road apiece,” Sam Houston raised a shaggy eyebrow. “I take it you’re a Unionist, then?”

“As you are yourself, sir,” Carl returned evenly.

“Not an easy thing to be, these days,” Houston rumbled. “It’s the hardest choice to make, Becker; between the difficult but correct—and that which seems most inviting but wrong. And when it calls you to go against your friends? Houston says it is a rocky path, a rocky path indeed.” He shot a very shrewd look at the younger man, adding, “They are waiting for Houston to take an oath, you know. An oath of loyalty to a Confederacy which the state has been rushed willy-nilly to join, without agreement or even discussion among the people, save those true believers.”

“What will you do, sir?” Carl asked before he thought better of it. The old man smiled a sharp-edged smile, the smile of a lion with a bit of fight in him yet. And he must have a bit of fight left, for he was speaking of himself theatrically, as was his fashion, as if he were another person entirely.

“Think you that Houston would share his decision until the time is come for it?” Then he sighed again, looking very tired and every single one of his long years, and lapsed into ordinary speech. “In truth, I have not made up my own mind over what is the best course for our people, out of all those that are available to me. Our people . . . contrary, fractious and quarrelsome as they are; it is a tragedy that it came to this pass. I think sometimes I have lived too long, to see such dissolution of everything that we fought for, that our fathers fought for. This . . . this peculiar institution of ours, it is a paltry passing thing. To see good men, noble men, stout and patriotic citizens, rush to dismember our Nation on its behalf; that fills a bitter cup to the brim. It’s not a cup that will pass from us, I fear. We . . . all of us . . . will be forced to drink of it, to the very last vile dreg.”

He had tears in his eyes. Carl did not think they were feigned, even if the old man was notorious for a penchant for the dramatic.

“You think there will be a war over this?” he asked.

Houston nodded sadly. “Of that I am most assured. I cannot pretend to know who will launch the first provocation, but it will hardly matter, once the smoke clears.” He pressed his left hand against his opposite shoulder and added, fretfully, “The wound I took at Horseshoe Bend still bleeds, you know. As if to remind me of what war is like, what it costs. Do you need such reminders?”

Carl shook his head. “No. I dream of it still.”

Houston jerked his chin at the cluster of boys in grey, some of them dancing a quadrille with the girls in their bell-shaped skirts, under the apple trees hung with lanterns in the twilight.

“They will not heed any of your apprehensions or mine, either, I fear. They will disparage the Yankees, rush onto the field of war and think it a holiday to fight their own brothers, their cousins.”

“President Lincoln will not just let the confederated states go?” Carl asked, from simple curiosity.

Houston shook his head. “He cannot; he is not that sort of man. He was a representative from Illinois for a couple of years, when I was first sent to the Senate after annexation. I saw him now and again. We did not agree on much, I fear.”

“What did you think of him, from first hand?” Carl asked. This was heady stuff, speaking to someone who had actually met the man whose election had brought the whole awful, festering dispute to a head.

Houston considered for a moment, finally answering, “A simple man of the frontier; like you and me, of no great education other than what he could scratch up for himself. A tall, homely and ungainly fellow, but it would be a great mistake to dismiss him as the backwoods bumpkin he appears to be. If I am any judge, I think he uses that semblance to disarm his opponents in court, or in debate. He is said to be good company with an amusing fund of stories, and none better at winning a hostile audience to his side, but he is often given to black melancholy. We had some slight communication . . . ” the old man stopped himself, “on some trivial matter, of late. But it was enough for me to form an impression of fierce and unyielding determination. He will do what it takes, to his last breath, to preserve the Union.” Houston sighed again, deeply morose and added, “He is abused by so many and with such vigor and frequency on every aspect of his character and person, I confess that of late I find myself feeling considerable fellow-sympathy for him on that score!”

“I’ll say that for him.” Carl remarked. “He has aroused more bitter personal enmity in Texas than you ever did. Until this last year I did not think it possible!”

Houston laughed in delight. “That is so, and he only had a year or two to work at it, too. No mean accomplishment, that!” He lifted his head, reminding Carl again of a lion, and fixed him with a speculative look. “So, what are you going to do now, young Becker? The difficult right or swallow your considerable misgivings—don’t equivocate, man, I know you have them—and join the rest of the crowd?”

“I’ll do what’s best,” Carl answered firmly. “What is best for my family and in the eyes of those I honestly respect. It may work out to be the best for Texas, even.”

“Be sure you’re right, then go ahead? Didn’t turn out well for one man I knew who used to say that,” Houston said, with a steely glint. “But it’s no other’s decision but yours, even if it is your choice to just to go back to your place and grow cabbages.”

“My place is up in the hills, on the upper Guadalupe, sir,” Carl answered, with a grin. “I make a good living from it. But in cattle and orchards, not cabbages. This is not a fight I choose.”

“As long as the fight doesn’t choose you,” Houston rumbled. Then he sighed heavily and said again, “I fear that Houston has lived too long… too long for this. All the same, young Becker… I wish you luck.”

“I saw him with my husband, talking long in the evening,” Oma Magda said, “but I did not know, until Margaret told me, that it was General Houston himself. He was the governor at that time, although not for many days longer. The legislature had passed a law, saying that all public officials must swear an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy. And he would not do it, so he stepped down from the office and went to his home, rather than fight it or swear falsely.”

“General Houston, himself?” the faces of the boys lit up. “Truly, did you see him, Oma? What did he look like?”

“Like an old man, and very weary.”

“What did he tell Opa?” Marie asked, and Oma Magda answered, “To be sure he was right, and then to go ahead.”

“I’ll not join with them,” Carl whispered to her on the last night of their stay in Margaret’s house, alone in the bed that Margaret had allotted to them. “So you need not worry about me looking to the sound of trumpets and drums.”

“I had no such concern,” Magda answered, although she did. She had seen her husband’s face, at being excluded from the company of his old friends. “But Margaret . . . she has the same apprehensions, yet her husband and sons are volunteering. Do they not see matters in the same light as you? Why do you alone stand aside, while everyone else here rushes pell-mell?”

“Two reasons,” Carl answered, after some moments. “Firstly, slavery is wrong. I’ll not be drawn into defending it, not even by Jesus Christ himself, come down from the cross to explain to me why. Secondly, I do not think the confederated states can win.”

“Why, my heart?” she settled into the curve of his arms around her, the rumble of his voice against her ear. “Why are you so sure of this, against the urgings of all your old friends, your comrades?”

“Blame your father,” he answered wryly. “Your father, who gave me books and taught me to think. Jack, too, had a part in forming my convictions. I’ve been sure of this, ever since I began to notice that all the things we buy at Specht’s or at Hunter’s, if it’s manufactured, mostly it comes from the north. Our Colt revolvers and other guns, as I pointed out to young Stoddard that first evening we were here, for all the good it did me. The books we buy? All printed in the North. Charley Nimitz hopes someday to see a railway built, to bring people to his fine hotel, but where are all those steam engines built? Who builds the ships that bring all these goods around to Galveston or down to New Orleans? I know there are shipyards in the South, but most of them are in the North. Where would Johann have gone to study medicine, if not back to Germany? He might have gone to Boston or some other school… in the North. There is no school where he might have studied in the South!” He sighed, seeming melancholy.

Magda tightened her arms around the dear sweet shelter of him and whispered, “So, my heart . . . surely it cannot be that bad!”

“Yes, it can,” he continued. “One more matter, my dearest Margaretha—where do all the new immigrants go, such as yourself?” Playfully, he squeezed her breast. “Herr Pastor Altmueller pointed it out; they go to the North. What matter if some of them stop in the factories, or tend small farms in the territories? To the free soil states, where they do not have to compete with slave labor! What are we, my heart? We are farmers, with our little orchard and our cattle herd. So are most of us. We grow what we need and sell the rest, buying only what we need and can’t make ourselves. I fear that we are rather like the Indians. We have our own ways, and like them best. We’ll change the Comanche as we are stronger, and the North will change us as they are stronger still. In the end, all I can do is attempt to keep my own safe; you and the children, my land and my friends. I took a vow once,” he said, and Magda knew from the way that his voice changed that he was coming close to speaking of that which he had never spoke of before to her. “I took a vow on the blood of my brother, which was splattered all over me—that I would never put my trust in a man who wore a fancy uniform. And that I would not follow a leader who would surrender. The Confederation will surrender if it comes to war. Not right away, they’ll put up a good fight—but in the end, they will surrender. Jack and General Sam are the two best soldiers I know. They’ll have no part in this madness and I will heed their counsel over any other.”

Margaret saw them away in the morning, standing on the verandah, neat as a pin in her plain morning dress with a large apron tied over all. Her husband stood with her and young Peter also, the Doctor saying in some surprise, “Were you leaving today? It seems as if you have just barely arrived, but it has been most pleasant to have you visit again.” He shook Carl’s hand warmly, and then seemed to remember something. “Does that shoulder of yours still bother you, then?”

“No. Hasn’t in years, except when the weather changes.”

Margaret embraced him, and her eyes seemed to shine with tears. “Come back soon, little brother! Don’t you dare stay away for so long, again! And Margaretha, dear sister! You must write me, often and again and again. I would see the children again also, before they are grown men and women!” Over her shoulder, Magda saw her husband holding out his hand towards Peter for a farewell handshake. But with a stony look on his face, the younger man placed both of his hands behind his back and stared his uncle down.

She heard Carl say very quietly, “Goodbye, Peter. Stay safe. If for nothing else, then do so for your mother’s sake.” Peter turned on his heel and went inside without a word. Magda did not think anyone else noticed in the flurry of farewells, as Daddy Hurst began helping Sam and Hannah up into the brake. In a few minutes they were away, the gravel flying from beneath the horse’s hoofs and the iron-shod wheels.

“That was so much more enjoyable than I had thought it would be,” Magda said, breathlessly, although her husband seemed hardly to have heard her. He looked out the window as the brake rolled by the apple trees, as if he looked into the far distance and did not see them at all.

In Friedrichsburg, the stage stopped to let down passengers at the back of Charley Nimitz’s hotel, at a little roofed shelter. The last leg from Neu Braunfels had been quite crowded. Hannah and Sam had needed to sit on their parents’ laps, as the stage bowled along at a great rate, swaying effortlessly over the smoothly rolling road that Magda and Vati, with their friends in the first wagon train, had crossed with such effort.

“So glad to see the oak trees again,” Magda said, as Carl lifted Hannah down to her. She stretched on tiptoe to relieve the cramp in her legs from sitting in one position for so long. “Wake up, Hannah my duckling… we’re nearly to Vati’s. We’ll have to walk from now, but it’s only a little way.”

The coach was late, it was already twilight and the lanterns were lit in Charley’s garden; the lanterns that hung from the pergolas that supported Charley’s grape and hop arbors. The coachman’s assistant threw down their bags from the luggage van into a mound, from which the passengers must seek out their own.

“I traveled twice as far as this with only a blanket and an extra shirt,” Carl complained genially, as they pulled their own heavy bags to one side. “Why did we need so much, Margaretha?”

“Because of the children!” she answered. “And very respectable you would have seemed, wearing just a blanket to your own nephew’s wedding!”

“Mama, are we almost home, now?” Hannah asked plaintively.

Carl ruffled her hair, answering, “Yes we are, duckling, don’t you fret.” Over her head, he added to Magda, “I’ll carry her. We’ll take the bags into Charley’s place and I’ll come for them later.”

The smells of good cooking wafted from the kitchen at the back of the hotel and here was Charley, magnificently welcoming, walking down the path towards them and the other folk who had come in on the regular stage; the good bourgeois man of business, with a gold watch chain and fob stretched across his fine silk vest. He had grown out a good beard since Magda had first met him tending the Verein storehouse and doing magic tricks to amuse the very much younger Rosalie, back when Friedrichsburg was a clearing of half-built houses and simple cabins among the trees and the marks of Mr. Bene’s surveying party.

“Hello, and welcome home!” he called, as soon as he was within distance. “You must be tired; everyone always is. Don’t bother with your bags. I’ll send them along. How was the wedding and your good sister?” He kissed Magda’s hand with exuberant affection, grinning at Carl as if daring him to do anything about it. Once they had been rivals for her, but were still and always friends.

Carl didn’t rise to the bait. “I spent the whole two weeks thinking I would kill for some of your good beer,” he answered.

“Well then, stay and have some,” Charlie offered, with the greatest good cheer. “It’s suppertime, too. If you aren’t expected at your father’s yet, then sit down and break bread with us. I’ll have one of the boys hitch up the dog-cart and take you all home afterwards— what about that, hey?”

Magda’s resolve wilted; it was already late, past the time that Vati and Rosalie would have expected them. It would be a very great trouble now to walk to Vati’s house and put a meal in front of the children and themselves, and here was Charley, with a hotel kitchen at his disposal.

“Charley, you are an angel,” she answered gratefully.

Charley beamed, “Right this way, ladies and gentlemen, mesdames and messieurs! Welcome to the very finest hotel between the grand city of Austin and the very inviting metropolis of… I forget, is it San Diego, or Yuma? Three log cabins and a saloon, so I am told. Certainly it is the only place where you can procure a hot bath.”

“And clean sheets,” Magda joked. Charley always made her laugh, but he was no charming lightweight. He had an extremely good head for business on his shoulders and she realized with an interior giggle that he and Margaret would get along famously, if they ever met.

“And good beer,” her husband added meaningfully.

Charley laughed and led them into the hotel dining room through the garden entrance. “Ah, I believe that is known in Ranger parlance as a hint! Sophie, Sophie dear, look who is returned! Fresh from the amusements and excitements of the big city! I marvel they were able to drag themselves away.”

Sophie Nimitz, who had been Sophie Miller once upon a time, exchanged a look of amusement with Magda and asked, “Was it wonderful? Did you have a nice time in the city, Magda? You must tell me all about it!”

Carl said ominously, “You promised us beer, Charley. And food.”

“It was terribly . . . well, interesting,” Magda answered and the children chorused their own excitement and hunger.

Charley commanded, “Well, sit down, sit down. We’ll bring it, straight away. What’s the latest news, though? Has the war started yet?”

“No,” Carl shook his head. “But the governor resigned rather than take the oath of allegiance to the Confederacy. We heard about it the morning that we left. It was all over town.”

Charley was stunned out of his levity. “Is this true? He just . . . stepped down, like that? Without putting up any sort of fight at all? But he is the greatest man in Texas, how could that be?”

“Because he is the greatest man in Texas,” Carl answered heavily, as Sophie unobtrusively steered them towards an empty set of places at the table where the guests took their meals. “It would tear the state apart if he chose to call for people to take his side. He believes in the law and the will of the people.”

“And he is old, too,” Magda added with defensive sympathy for the man that she had watched now and again throughout that long evening after the wedding, “Older than Vati. He looked so very tired. He was at the party—after the wedding at Margaret’s house.”

“That makes it very strange, now, doesn’t it?” Charley still looked unaccustomedly grave.

Carl said, “It means the first time in almost thirty years that General Sam hasn’t been in authority of one kind or another in Texas.”

“A bit like having your father die, I’d think,” Charley observed.

Carl laughed shortly, “Worse. I thought more of General Sam than I ever did of my father.”

“I’ll bring you some beer, then,” Charley said and slapped Carl’s shoulder in a comradely way. “We’ll send him off with a toast of our own, to him. And then I’ve got a question for you and news of my own that you wouldn’t have heard.”

“Wonder what that can be?” Carl looked across the table, raising his eyebrows. “We’ve just come from Austin, I thought we would have heard everything there.”

“Here, to hold the children over.” Sophie brought a plate of bread and butter, and set it before the children. It’s pease-soup tonight and a ragout of smoked pork and pickled cabbage for main course. Apple pie for afters.” She twinkled merrily at Magda and added, “The pie should taste familiar, we bought the apples from you, I vow. Did you have such good food at your sisters?”

“We did, almost,” Magda answered tactfully and Dolph spoke up, “We had iced-cream, once. It was a very great treat. Aunt Margaret said the ice came all the way from New England on a ship, and then up from the coast in a special wagon.”

“It was almost as expensive as gold,” Magda marveled, “but very good, nonetheless.”

“Here you go!” Charley set down a couple of tankards as Sophie shook her head in disbelief, and pulled out a chair. “To General Sam! Prosit!” Carl and Charley solemnly struck them together, and drank deeply.

“That’s a toast that it’s an honor to drink, in water if nothing else,” Carl said and Magda knew he thought of the toast in the hall of Mayfield that he would not drink. “So, what is this great news that we haven’t heard, Charley?”

“Miss Magda’s little brother is home from Germany,” Charley answered, with a grin. “Surprised, eh? I knew you would be! He came up on the stage from San Antonio, four days ago. He’s at your father’s now.”

“Johann!” Magda cried, half delighted but worried all the same. “He’s home? But why? He was supposed to stay in Germany and study until the end of summer.”

Her little brother had been timid and serious as a boy, as much as Friedrich, his twin in every other way, had been a lively and reckless young spark. He had gone to study medicine in Germany six years before, with the assistance of Vati’s many friends who thought that Johann showed much promise and that there was need for a doctor well-trained in a way that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

“As for why?” Charley spread his hands and shrugged. “Who knows, really. He told me he became worried about a blockade. That fighting might begin before he could get home. If he didn’t come at once, he might not be able to come home for years.”

“He looks very much the earnest young doctor.” Sophie added, “He has a mustache like Chancellor Bismarck’s, but it doesn’t help. He still looks very young. Now, I bring you the soup! I was waiting to see your faces, when Charley told you!” She bustled away towards the kitchen, as Carl said, “Well, at least he won’t want to enlist, along with all the other young sparks. Since he just got home, he’d probably want to stay a while.”

“You’d be surprised,” Charley answered confidently. “You’d be surprised indeed.” He looked thoughtfully at Carl, “You know, now that the Army is gone—the US Army, I mean—we’re in a bit of a perilous situation, with no protection from the Indians and all. I’ve been recruiting men for our own company. It’ll be official, part of the state army and all. Call ourselves the Gillespie Riders. I’d like you to come in with us. You’d be a Godsend, with your experience.”

“No,” Carl said at once. Charley looked a little taken back.

“You’re sure?” he asked and Magda looked from his face to her husband’s obstinate one.

“Charley, if it’s something approved by the Committees of Public Safety and the secessionists in the legislature, there’s going to be that oath involved. General Sam wouldn’t take it and I’m damned if I’ll take it, either.”

“Be reasonable! We have to do something to protect our families,” Charley said.

Carl answered wearily, “I already do that. My neighbors and our sons and hired hands; we’ll patrol our lands just as we have, whenever there’s reports of strangers. But this oath business stinks like an over-full privy on a hot summer day.”

Charley looked at his beer stein and ventured carefully, “It might not be a bad idea, you know… to take it. There’s a lot of suspicion about where we stand, now that it’s come down to secession. Maybe we should make a demonstration. Let there be no doubt about our loyalties. Prove that we stand with our neighbors—with all of them, not just the Germans. Lindheimer says—”

“I know what he says.” Carl finished his own beer and set the stein down with a snap. “And I think I proved where my loyalties are a long time ago. I don’t reckon I need to prove them again.”

“So we thought,” Oma Magda sighed. “So we believed for a time that we could look to ourselves… that we would be left alone, in our high hills. That if war came, it would somehow pass us by. We were wrong. But as much as I thought about it, I could not find where we might have done anything different and still held ourselves with honor and pride.”

* * *

From The Harvesting: Chapter Six: Indianola

It was a matter of some excitement and no little apprehension for Magda Vogel Becker to journey forth from the house on Market Street. In all of twenty years since coming to Texas as a settler under the Verein auspices, she had gone no farther than her husband’s land on the upper Guadalupe, save once to Austin. Her brothers, her sons, her husband, her brother-in-law and many of their friends—oh, they had traveled widely, the length and breadth of Texas, to New Orleans, and Mexico, to California—even returning to Germany! Bound with household and children, for care of Vati and then by the dangers of war, she had always remained by the home hearth and been happy in the main to do so. The welfare of the shop tugged at her like a fretful and frail child. For worry over the daily care of stock, accounts and the needs of customers, she might have very easily given up this long trip of Hansi’s contriving.

But this was the slow time, after the turn of the year and before the trail season opened. Hansi was of the opinion that they might cut better bargains among the merchants and in the warehouses of San Antonio or Indianola. It was resolved among them all that the shop could do without her care for some weeks, while she and Anna saw to purchasing fresh stock. Of late she had felt something of an urge, even the necessity, of seeing other horizons, other skies. Anna felt it even more urgently; and it was only the need to pacify her sister Liesel’s fears and worries for her oldest child that she had consented to participate in this excursion. Anna had her heart sent on going. Magda could not withdraw now, or her sister would use the lack of a proper chaperone to keep her oldest daughter close at hand.

Magda now sat with Lottie on her lap, Anna beside her, on a bench at the back of the Nimitz Hotel, waiting for the mid-week stage to San Antonio. Hannah played hopscotch by herself on a set of squares she had scratched in the dirt nearby. There were a handful of men also waiting the stage, but they respectfully tipped their hats to the women and stood a little apart. Magda did not know any of them—Americans, she supposed, as they spoke to one another in English. She cringed inwardly at the extravagant cost of such a journey, first to San Antonio, and thence to Victoria and Indianola, but Hansi had insisted that it was actually a sensible economy. She and Anna could not be spared from the shop together for the length of time that a journey with his wagons would entail; better to travel swift and sure by the stage, and lodge with friends.

Anna looked sideways around the edge of her modish straw bonnet. “Auntie, you are fidgeting again! You should not worry so. Mama will manage, with the help of Rosalie and Vati.”

“I am sure,” Magda replied swiftly, but she sighed and added, “I wish that we had not heard about Uncle Simon.”

“It was very kind of his nephew to write, and to return all of Vati’s letters,” Anna said. Magda thought again of how Vati had looked when he opened the parcel from Germany and learned of the death of his friend from the old days in Ulm. Simon the goldsmith, with whom he had exchanged letters for twenty years, dearest friend for another thirty years before that. Vati had looked like a withered old gnome. He had taken the parcel of letters into his room upstairs and not come out for several hours. When he did, it was to insist that nothing was wrong. He would dig in the garden for a while and then walk over to commiserate with Pastor Altmueller.

“It was always Uncle Simon’s thought that Vati should do a book of his letters from Texas,” Magda said now. “And Rosalie will cheer him up, as well as make sure he does not boil his socks in the soup and leave his spectacles in all sorts of places.” Rosalie, blooming like her namesake in the first year of her marriage to Robert, had promised to come and stay with him for the duration of their absence from the store.