The pivotal battle of the Civil War was fought 150 years ago this week, in the hilly countryside around the little Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. Vicksburg fell to the Union also on July4th, but the eyes of everyone focused on the titanic struggle at Gettysburg. This is a link to an interactive map of the three days’ battle, showing how it developed, and concluded with Pickett’s charge against the Union position – a charge which broke Lee’s Army, and decimated the Texans of Hood’s Brigade – to include my fictional Vining family. Of Margaret Vining Williamson’s four sons, only the youngest, Peter, would survive.

After Gettysburg, Lee’s Army would fight on – but never on the offensive again, always in defense.

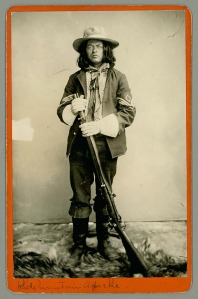

His name wasn’t really Mickey Free, and he wasn’t really an Apache Indian. The legendary Al Sieber, chief of Army scouts in the badlands of the Southwest after the Civil War once described him as ‘Half Mexican, half Irish and whole S-O-B.’ Mickey Free was one of Sieber’s scouts, enlisted formally into the US Army in the early 1870s at Fort Verde, Arizona, eventually rising to the rank of sergeant. He was a valuable asset to Sieber and the Army as a scout and interpreter as he was fluent in English, Spanish and the Apache dialects. Most observers assumed that Mickey Free was at least half-Apache, though. He raised a family, served as a tribal policeman and when he died, was buried at his long-time home on the reservation of the White Mountain Apache. But he was just as Al Sieber had said – Mexican and Irish – and his birth name was Felix Martinez. And what many didn’t know was that Mickey Free was entangled inadvertently in the bitter and ongoing war between the Apaches and the whites long before his enlistment in the Army.

His name wasn’t really Mickey Free, and he wasn’t really an Apache Indian. The legendary Al Sieber, chief of Army scouts in the badlands of the Southwest after the Civil War once described him as ‘Half Mexican, half Irish and whole S-O-B.’ Mickey Free was one of Sieber’s scouts, enlisted formally into the US Army in the early 1870s at Fort Verde, Arizona, eventually rising to the rank of sergeant. He was a valuable asset to Sieber and the Army as a scout and interpreter as he was fluent in English, Spanish and the Apache dialects. Most observers assumed that Mickey Free was at least half-Apache, though. He raised a family, served as a tribal policeman and when he died, was buried at his long-time home on the reservation of the White Mountain Apache. But he was just as Al Sieber had said – Mexican and Irish – and his birth name was Felix Martinez. And what many didn’t know was that Mickey Free was entangled inadvertently in the bitter and ongoing war between the Apaches and the whites long before his enlistment in the Army.

He was born in Santa Cruz, Sonora, the son of Jesusa Martinez and Santiago Tellez, who was said to be Irish, or part Irish. When Santiago Tellez died, Jesusa married John Ward, and took her small son to live on Ward’s small ranch on Sonoita Creek, southeast of Tucson. Sonoita was very much out of the way – and even more so late in 1860 or early 1861, when John Ward’s ranch was raided by a party of Arivaipa Apaches bound on stealing stock. Felix Martinez, then about twelve years old was captured and taken also; some accounts have it that he tried to climb up into a fruit tree to hide. But he was captured anyway – and taken away by the raiders. Other accounts have it that Felix’s stepfather was more concerned about the loss of his cattle than the boy, and only belatedly demanded the return of both. Some months later, the officer commanding at the nearest Army post, Fort Buchanan ordered a detachment of soldiers to go out with John Ward and an interpreter, towards the area around Apache Pass. It was supposed that the boy and the stolen cattle were there, in the area where the Overland Mail stage road passed through the mountains. The military detachment was under the command of a young and fairly recent West Point graduate, one Lt. George Bascom, who was later charitably described as an officer, a gentleman … and a fool.

Near the Apache Pass stage station, Bascom and his party encountered the Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise. Bascom asked for a meeting in a council tent with Cochise, and began it badly by demanding return of the boy and the stolen stock. Cochise answered honestly and fairly; he did not have them – but given time, he promised to find out who did and return them. Up until that very day, Cochise had been friendly and conciliatory to whites; indeed, the Overland Mail stages only operated because Cochise and his warriors allowed it. Bascom arrogantly repeated his demand for immediate return of the boy Felix – and informed Cochise that he and his party would be held hostage against the boy’s return. Bascom’s soldiers had been instructed previously to take Cochise and his party prisoners but Cochise had a knife. In the ensuing fracas, he slashed his way free, although his companions – including his own brother and two nephews – were captured. Bascom took his Indian hostages back to the shelter of the Apache Pass stage station. Meanwhile, Cochise and his warriors attacked an American supply train and captured three hostages, offering them to Bascom in exchange for his brother and nephews. Bascom refused – he would accept only Felix Martinez and the stolen cattle for Cochise’s relatives. Cochise killed his captives, before escaping into the Sonora – and Bascom hanged his, before returning to Fort Buchanan. The war by Apache on the Federal Army and the white settlers of Arizona was on … and very shortly to be joined by the greater civil war between the Union and the Confederacy. In all of that bloody conflict, the matter of 12-year old Felix Martinez Ward was shelved. It is entirely likely that only his mother cared very deeply; his stepfather didn’t seem to, the military commander in the region soon had bigger problems, and Lt. Bascom was killed in battle at Val Verde, New Mexico territory the following year. The Martinez-Ward family seems to have concluded that the boy was dead, or gone far beyond reach, although a half-brother was surprised many years later to discover the truth.

So, what happened to Felix Martinez Ward? Pretty much what happened to many Anglo and Mexican boys of a certain age taken captive by the Tribes. He was adopted into the White Mountain Apache tribal division – treated with relative kindness and trained in the traditional ways. And eleven years after his abduction from his stepfathers’ ranch, Felix Martinez Ward enlisted in the US Army as an Apache scout under the name Mickey Free. He participated in the US Army’s campaign to capture the last stubborn Apache band led by Geronimo – and there exist many pictures of him, either alone or with the other Apache scouts. He is fairly easy to pick out from a group, for although he has long, thick hair to his shoulders … he has a rather round face, with a snub nose and a cleft in his chin. He does not look Indian in the least. Put him into the chorus line of Riverdance, and he’d blend right in.

He lived to a ripe old age on the White Mountain Reservation, and was buried there, leaving many descendants.

First up – I have a post up at the Unusual Historicals website, as part of their series on women in war. My post is about Elizabeth van Lew, the Union’s lady spy in Richmond, during the Civil war.

And on Saturday, March 23rd, I’ll be one of thirty or so local authors at the Bedford Public Library as part of their “Romancing the Books” event. I’ll be doing a reading from one of my books – and many of the authors will have their books for sale. Check it out, if you are in the Dallas-Fort Worth area this weekend!

It was said of Texas that it was a splendid place for men and dogs, but hell for women and horses. Every now and again though, there were women who embraced the adventure with the same verve and energy that their menfolk did; and one of them was a rancher, freight-boss and horse trader in the years before the Civil War. She is still popularly known as Sally Skull to local historians. There were many legends attached to her life, some of them even backed up by public records. Her full given name was actually Sarah Jane Newman Robinson Scull Doyle Wadkins Horsdorff. She married – or at least co-habited – five times. Apparently, she was more a woman than any one of her husbands could handle for long.

Sarah Jane, later to be called Sally was the daughter of Rachel Rabb Newman – the only daughter of William Rabb, who brought his extended family to take up a land grant in Stephen F. Austin’s colony in 1823; an original ‘Old 300’ settler. (In Texas, this is the equivalent of having come on the Mayflower to New England, or with William the Conqueror to England.) Rabb and his sons and daughter, with their spouses and children – including the six-year old Sally – settled onto properties on the Colorado River near present-day La Grange. Texas was even then a wild and woolly place, and several stories about those years hint at how the frontier formed Sally the legend – well, that and the example of her mother, a formidable woman in her own right. One story tells that Rachael and her children were safely forted up in their cabin, with hostile Indians trying to break in through the only opening … the chimney. Rachel threw one of her feather pillows onto the hearth and set fire to it, setting a cloud of choking smoke up the chimney. Another time – or possibly the same occasion – an Indian raider was trying gain entry by lifting the loose-fitting plank door off it’s hinges. When the Indian wedged his foot into the opening underneath the door, Rachel deftly whacked off his toes with one swipe of an ax.

Sally first married in 1831, two years following the death of her father. She was only 16; not all that early in a country where women of marriageable were vastly outnumbered by men. Her husband, Jesse Robinson was twice her age, also an early settler, and had a grant on in the DeWitt colony near Gonzales. At about that time, Sally registered a stock brand in her own name; she did not go undowered into the wedding, which turned out to be a bitterly contentious one. She had inherited a share of her father’s herd – but signed the registry with an ‘x’ indicating that she was most likely illiterate. But if Sally had been shorted in the matter of book-learning, she had not been when it came to making a living in frontier Texas. Sally rode spirited horses, and astride – not with a lady-like side-saddle. She tamed horses, raised cattle, managed a bullwhip and a lariat, spoke Spanish fluently and was a dead shot with the pair of revolvers which customarily hung from a belt strapped around her waist. There are no daguerreotypes or any sketches from life of Sally, only brief descriptions by those who met her and took note now and again. “…Superbly mounted, wearing a black dress and sunbonnet, sitting as erect as a cavalry officer, with a six shooter hanging at her belt, complexion once fair but now swarthy from exposure to the sun and weather, with steel-blue eyes that seemed to penetrate the innermost recesses of the soul…” was the testimony of one obviously shaken individual. More »

“From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.”

When I was deep in the midst of researching and writing the Adelsverein Trilogy, of course I wound up reading a great towering pile of books about the Civil War. I had to do that – even though my trilogy isn’t really about the Civil War, per se. It’s about the German settlements in mid-19th century Texas. But for the final volume, I had to put myself into the mind of a character who has come home from it all; weary, maimed and heartsick – to find upon arriving (on foot and with no fanfare) that everything has changed. His mother and stepfather are dead, his brothers have all fallen on various battlefields and his sister-in-law is a bitter last-stand Confederate. He isn’t fit enough to get work as a laborer, and being attainted as an ex-rebel soldier, can’t do the work he was schooled for, before the war began. (Interesting work, this; putting myself into the minds of people who were seeing things as they developed, day by day and close up; with out the comforting overview of hindsight.) This was all in the service of advancing my story, of how great cattle baronies came to be established in Texas and in the West, after the war and before the spread of barbed wire, rail transport to practically every little town and several years of atrociously bad winters. So are legends born, but to me a close look at the real basis for the legends is totally fascinating and much more nuanced – the Civil War and the cattle ranching empires, both.

Nuance; now that’s a forty-dollar word, usually used to imply a reaction that is a great deal more complex than one might think at first glance. At first glance the Civil War has only two sides, North and South, blue and grey, slavery and freedom, sectional agrarian interests against sectional industrial interests, rebels and… well, not. A closer look at it reveals as many sides as those dodecahedrons that they roll to determine Dungeons and Dragons outcomes. It was a long time brewing, and as far as historical pivot-points go, it’s about the most single significant one of the American 19th century. For it was a war which had a thousand faces, battlefronts and aspects.

There was the War that split Border States like Kentucky and Virginia – which actually did split, so marked were the differences between the lowlands gentry and the hardscrabble mountaineers. There was the war between free-Soil settlers and pro-slavery factions in Missouri and in Kansas; Kansas which bled for years and contributed no small part to the split. There was even the war between factions of the Cherokee Indian nation, between classmates of various classes at West Point, between neighbors and yes, between members of families.

How that must have broken the hearts of men like Sam Houston, who refused to take a loyalty oath to the Confederacy, and Winfield Scott, the old soldier who commanded the Federal Army at the start of the war. Scott’s officers’ commission had been signed by Thomas Jefferson: he and Houston had both fought bravely for a fledgling United States. Indeed, at the time of the Civil War, there were those living still who could remember the Revolution, even a bare handful of centenarians who had supposedly fought in it. For every Southern fireater like Edmund Ruffin and Preston Brooks (famous for beating a anti-slave politician to unconsciousness in the US Senate) and every Northern critic of so-called ‘Slave power” like William Lloyd Garrison and John Brown… and for every young spark on either side who could hardly wait to put on a uniform of whatever color, there must have been as many sober citizens who looked on the prospect of it all with dread and foreboding.

There are memories, as was said of a certain English king, which “laid like lees in the bottom of men’s hearts and if the vessels were once stirred, it would rise.” So is it with the memory of the American Civil War. The last living veterans are long gone, the monuments grown with moss and half forgotten themselves; even some of the battlefields themselves are built-over, or overgrown. But still, the memories, the interest as well as the resentments linger, waiting for the slightest motion to stir them up. The Civil War is still very much with us. Consider books like Cold Mountain, The Killer Angels, and Gone With the Wind, and documentaries like Ken Burns The Civil War. Every weekend, somewhere across the United States there are re-enactor groups, putting on the blue or the grey and shooting black-powder blanks at each other.

An argument about the causes of it all tends to be just as noisy and inconclusive, and boils down to the academic version of the above. The participants agree on some combination of slavery (or its extension beyond the boundaries of certain limits), states’ rights and the competing economic interests which would favor a rural and agricultural region or an urban and industrial one. What are the proper proportion and combination of these causes? And was chattel slavery a root cause or merely a symptom?

Whatever the answer, sentiment about slavery, or “the peculiar institution” hardened like crystals forming on a thread suspended in a sugar solution for some twenty or thirty years before the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In a large part, that hardening of attitudes was driven, as such things usually are, by the extremists on either end of the great lump of relative indifference in the middle. At the time of the Revolution, one has the impression that chattel slavery in the American colonies was something of an embarrassment to the founding fathers. No less than the eminent Doctor Johnson had acidly pointed out the hypocrisy of those who owned slaves insisting on rights and freedom for themselves. For quite some decades it seemed that slavery was on the way out.

Of course it cannot just slip out of mind, this war so savagely fought that lead minie-balls fell like hailstones, and the dead went down in ranks, like so much wheat cut down by a scythe blade, on battlefield after battlefield. Units had been recruited by localities; men and boys enlisted together with their friends and brothers, and went off in high spirits, commanded by officers chosen from among them. At any time over the following four years, and in the space of an hour of hot fighting before some contested strong point, there went all or most of the men from some little town in Massachusetts and Ohio, Tennessee or Georgia. Call to mind the wrenching passage in Gone With the Wind, describing the arrival of casualty lists from Gettysburg, posted on the front windows of the newspaper office for the crowd of onlookers to read, and the heroine realizing that all of the young men whom she flirted and danced with, all the brothers of her friends and sons of her mothers’ friends . . . they are all gone. As an unreconstructed Yankee, GWTW usually moves me to throw it across the room. But Margaret Mitchell grew up listening to vivid stories from the older generation and that scene has the feel of something that really happened, and if not in Atlanta, then in hundreds of other places across the North and South.

No wonder the memory of the Civil War is still so fresh, so terribly vivid in our minds. A cataclysm that all-encompassing, and passions for secession, for abolishing slavery, for free soil and a hundred other catch-phrases of the early 19th century . . . of course it will still reach out and touch us, with icy fingers, a not-quite clearly seen shadow, draped in ghostly shades of grey and blue.

Recent Comments