In some not inconsiderable ways, heading west along the Platte River trails might have been seen as a kind of working holiday for emigrants in the years before the Gold Rush. While there was a lot of brute physical work involved in moving the wagons or the mule-train the requisite twelve or fifteen miles farther west each day, the charm of and camping under canvas every night, and preparing meals over an open campfire twice or three times daily must have worn very thin… it may have been not much more onerous then the daily round of chores attendant on an 19th century farmstead. Add in camaraderie among the party, the fairly easy going on the first third of the trail to California or Oregon, opportunities to hunt and explore new horizons — horizons unimaginably wider than what they had been used to, back in Ohio or Missouri — sights that were strange and rare to ordinary farm folk.

The Platte River Valley itself was one of those st riking vistas; often called the “Coast of Nebraska; it so resembled a flat, shimmering ocean, edged with sand dunes. It appeared to be somewhat below the level of the prairies emigrants would have been crossing, since departing from Independence, St. Joe or Council Bluffs. To some emigrants it appeared like a vast, golden inland sea, stretching to the farthest horizon. But it was the highway towards the mountains beyond Fort Laramie, a month or so of fairly easy traveling… even if the river water was murky with silt, the mosquitoes a veritable plague and wood for campfires very rare.

riking vistas; often called the “Coast of Nebraska; it so resembled a flat, shimmering ocean, edged with sand dunes. It appeared to be somewhat below the level of the prairies emigrants would have been crossing, since departing from Independence, St. Joe or Council Bluffs. To some emigrants it appeared like a vast, golden inland sea, stretching to the farthest horizon. But it was the highway towards the mountains beyond Fort Laramie, a month or so of fairly easy traveling… even if the river water was murky with silt, the mosquitoes a veritable plague and wood for campfires very rare.

The Coast of Nebraska offered another awe-inspiring vista; that of vast herds of buffalo. The Platte Valleywas their grazing ground and watering hole. Emigrants were astounded equally by the size of the individual buffalo— which could weigh up to 2,000 pounds— and the sheer numbers. Witnesses to stampedes of buffalo herds at various times and places along the Platte noted how the very ground shook, and the sound of it was like a heavy railroad train passing close by. This was heady stuff, to someone who had spent most of their life before this following a plow on a farm in Ohio, or Missouri. But more was yet to come.

In the vicinity of Ash Hollow, a deep draw— a wooded canyon near the present-day town of Lewellen, the widest and deepest of all those canyons descending to the Platte—emigrants found abundant wood for their fires, and springs of fresh, clean-tasting water. The river water was full of sand and “wigglers”, or other barely visible contaminants. Perhaps the affinity for coffee saved a certain number of lives, since water was boiled thoroughly in its preparation. There were emigrant graves at Ash Hollow, one of them being the last melancholy resting place of an aptly named Mr. Shotwell, of the 1841 Bidwell-Bartleson Party, accidentally killed by a gun. It discharged as he took it out of a wagon, by misfortune having turned the muzzle of it in his direction. The Sioux and the Pawnee fought a desperate battle there, sometime in the winter of 1835, where the Pawnee were so overwhelmingly thrashed that they withdrew towards the east and did not return unless in a strong war party. An emigrant passing through some eight years later noted bones and skulls scattered nearby.

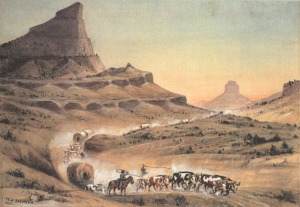

Westerly from Ash Hollow was the first of a remarkable series of bluffs; some saw it as a spectacular ruined fortress… a solitary castle, floating slightly above the level plain. But most saw it as resembling a courthouse; a great square edifice with a dome. Many curious travelers turned aside from the emigrant road to pay a visit, thinking it were only a mile or two away, deceived by the clear air… or as is more likely by the lack of anything man-made close by to compare it to, and their own inexperience at judging distances in the vastness of the trans-Mississippi west. But there was more…Courthouse or Castle Rock was only the prelude to a landmark dubbed by many emigrants as the eighth wonder of the world… Chimney Rock.

Westerly from Ash Hollow was the first of a remarkable series of bluffs; some saw it as a spectacular ruined fortress… a solitary castle, floating slightly above the level plain. But most saw it as resembling a courthouse; a great square edifice with a dome. Many curious travelers turned aside from the emigrant road to pay a visit, thinking it were only a mile or two away, deceived by the clear air… or as is more likely by the lack of anything man-made close by to compare it to, and their own inexperience at judging distances in the vastness of the trans-Mississippi west. But there was more…Courthouse or Castle Rock was only the prelude to a landmark dubbed by many emigrants as the eighth wonder of the world… Chimney Rock.

The historian of the Platte River road, Merrill Mattes calculated that 95% of the journals and guidebooks of the trail, as well as accounts of a journey along that stretch of the emigrant road made note of Chimney Rock. It was in sight for at least three or four days of travel along the trails on either side of the Platte, dancing like a mirage along the horizon at first, a slim column or obelisk, looking— as most observers agreed— like a shot-tower or a factory chimney. A scattering of travelers with a bent for scientific observation noted that it was composed of the same sort of materiel as the Courthouse rock, and rose to the same height as a nearby line of bluffs, concluding that the intervening materiel had eroded away. Many emigrants reported carving their name into the soft rock, competing to climb higher above their companions to place their own name… but the names carved there wore away within a few years.

If Chimney Rock was a curiosity and a wonder, most travelers spent the two days in which they passed by Scott’s Bluffs… a tall but oft-broken wall, which invited comparisons to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, or a vast walled Alhambra, with the river at its very foot, and turrets and buttresses towering into the sky. They were also moved by the sad story of the man it was named after; Hiram Scott, of William Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Brigade. Around about 1828, returning from a supply rendezvous in the mountains, Scott fell ill and was unable to travel any farther. He may have been abandoned by his companions, or urged them to leave him behind— stories varied.

There are, and would be other spectacular features of nature, along the trail towards Oregon, andCalifornia; but it was an irony of the trail that these and other lesser spots were encountered in roughly the first third of the journey, and where… unknown to most… the travel would be by far the easiest. Eventually, the emigrants would be too hungry and exhausted, desperate to get over that last barrier to stop and admire such places, in the same leisurely way they had appreciated Scott’s Bluffs and Courthouse Rock.

Recent Comments