Our maternal grandmother, Granny Jessie, tiny and brutally practical, was not particularly given to fancy and fantasies. When she talked of old days and old ways, she talked of her girlhood on her fathers’ ancestral acres, a farm near Lionville, Chester County, Pennsylvania; of horse-drawn wagons, and cows and cats, and how pigs were cleverer than dogs. Of how she and her sister and brother would have to stop going down to the pig-pen early in the fall, lest they become too fond of an animal whose fate it was to be butchered for ham, and bacon, roasts and sausage and scrapple to last the winter through. Of how she played on the Lionville boys’ baseball team, since there were not enough boys, and she was a tomboy and skillful enough to play first-base, and how her grandfathers’ house was once a fall-back way-station on the Underground Railway. (It was the inn in Lionville itself was the main way-station, with a secret room and a concealed access to the woods, or so said Granny Jessie.) It was all very prosaic, very American, a breath away from the Little House books and so very familiar.

Our other grandmother Granny Dodie’s stories, even if she did not have a spell-binding repertoire, were touched with fire and enchantment because of the very unfamiliarity of the venue… a row-house in Liverpools’ Merseyside, a few streets away from there the Beatles had come from, where Granny Dodie had grown up the youngest of a family of nine, sleeping three in a bed with her older sisters. “The one on the side is a golden bride, the one by the wall gets a golden ball, the one in the middle gets a golden fiddle, “she recited to me once. “Although all I ever got of it was the hot spot!” All her brothers were sailors or dockworkers, and her ancestors too, as far as memory went. Even her mothers’ family, surnamed Jago and from Cornwall — even they were supposed to have grafted onto their family tree a shipwrecked Armada sailor. Granny Dodie insisted breathlessly there was proof of this in the darkly exotic good looks of one of her brothers. “He looked quite foreign, very Spanish!” she would say. We forbore to ruin the story by pointing out that according to all serious historic records, all the shipwrecked Spaniards cast up on English shores after the Armada disaster were quickly dispatched … and that there had been plenty of scope in Cornwall — with a long history of trans-channel adventure and commerce — to have acquired any number of foreign sons-in-law. She remembered Liverpool as it was in that long-ago Edwardian heyday, the time of the great trans-Atlantic steamers, and great white birds (liver-birds, which according to her gave the port it’s name) and cargo ships serving the commercial needs of a great empire, the docks all crowded and the shipways busy and prosperous.

One Christmas, she and my great-Aunt Nan discovered a pictue book— John S. Goodalls’ “An Edwardian Summer”, among my daughters’ presents, and the two of them immediately began waxing nostalgic about long-ago seaside holidays; that time when ladies wore swimsuits that were more like dresses, with stockings and hats. They recollected donkey-rides along the strand, the boardwalks and pleasure-piers full of carnival rides, those simpler pleasures for a slightly less over-stimulated age. But the one old tale that Granny Dodie told, the one that stayed my memory, especially when Pip and JP and I spent the summer of 1976 discovering (or re-discovering) our roots was this one:

“There are places,” she said, ” Out in the country, they are, where there are stone stairways in the hillsides, going down to doorways… but they are just the half the size they should be. They are all perfectly set and carved… but for the size of people half the size we are. And no one knows where they lead.”

Into the land of the Little People, the Fair Folk, living in the hollow hills, of course, and the half-sized stairways lead down into their world, a world fair and terrible, filled with faerie, the old gods, giants and monsters and the old ways, a world half-hidden, but always tantalizingly just around the corner, or down the half-sized stairway into the hidden hills, and sometimes we mundane mortals could come close enough to brush against that unseen world of possibilities.

From my journal, an entry writ during the summer of 1976, when Pip and JP and I spent three months staying in youth hostels and riding busses and BritRail … and other means of transportation:

July 9- Inglesham

Today we started off to see the Uffington White Horse, that one cut into the hillside in what— the Bronze or Iron Age, I forget which. We started off thinking we could catch a bus and get off somewhere near it, but after trying quite a few bus stops (unmarked they are at least on one side of the road) we took to hitch-hiking and the first person took us all the way there. He was an employee of an auctioneering firm, I guess & I guess he wasn’t in a hurry because he asked where we were going (Swindon & then to the White Horse) & said he would take us all the way there. It was a lovely ride, out beyond Ashbury, and the best view of the horse is from the bottom, or perhaps an aero plane. It’s very windy up here, very strong and constantly- I think it must drive the grass right back into the ground, because it was very short & curly grass. We could see for miles, across the Vale, I guess they call it. After that we walked up to Uffington Castle, an Iron Age ring-embankment, & some people were trying to fly a kite-it’s a wonder it wasn’t torn to pieces.

We sat for a while, watching fields of wheat rippling like the ocean & cloud-shadows moving very slowly and deliberately across the multicolored patchwork.

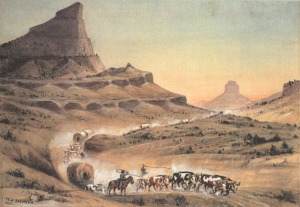

The man who brought us out advised us to walk along the Ridgeway, an ancient track along the crest of the hill, and so we did. It was lovely and oh, so lonely. Nothing but the wheat fields on either side and looking as if they went on forever.

We looked at Wayland’s Smithy, a long stone barrow in a grove of trees & when we got to Ashford, we found the Rose & Crown pub and had lunch. It was practically empty, no one but an elderly couple and their dog, a lovely black & white sheepdog, very friendly. Then we set off to walk and hitch-hike back to Highworth, but we picked the two almost deserted roads in Oxfordshire to do it, because it took nearly forever to get two rides. One got us from Ashbury to (indecipherable) and the second directly into Highworth. Both were women, very kind and chatty; I wish I knew what impulse people have which make them pick up hitch-hikers. What I do know is that the loveliest sight is that of a car slowing down and the driver saying “Where are y’heading for?”

Thirty years later I remember how charmed we were by the people who gave us rides— the auctioneers assistant who was so taken in by my reasons for seeing the White Horse that he decided he had to see it himself, and the two women— both with cars full of children— who were either totally innocent of the ways of this soon-to-become-wicked-world, or had unerring snap-judgment in deciding to slow down and pick up three innocent and apparent teenagers. (I was 22 but was frequently and embarrassingly informed that I looked younger than the 16 year-old Pip, and JP was 20, but also must have looked innocent, younger and harmless.)

With their assistance, we spent a lovely day, in the sun and wind, in the uplands along the Ridgeway, examining the form of a running horse, cut into the turf on a chalk hillside, an ancient fortress, a legendary dolman tomb, and an ancient highway along the backbone of Britain … always thinking that just around the next bend would be the stairway into the hollow hills, and the giants and fair folk of old … Adventure and peril just as Grannie Dodie said it would be in the lands of our ancestors … always just around the corner

Recent Comments