(Proper but desperate young Boston belle, Sophia Brewer is escaping from a number of demons, including her brutal and sociopathic brother, Richard. In her journey, she has been met with unexpected kindness, on her way to Kansas City to possible employment as a Harvey Girl.)

(Proper but desperate young Boston belle, Sophia Brewer is escaping from a number of demons, including her brutal and sociopathic brother, Richard. In her journey, she has been met with unexpected kindness, on her way to Kansas City to possible employment as a Harvey Girl.)

Chapter 8 – Away Into the West

If Heaven were not as blissfully comfortable as a soft berth made up with crisp white sheets, Sophia thought as she slid between those sheets, then she would prefer spending eternity in a Pullman berth, rather than the glorious hereafter. She ached with weariness in every limb that did not ache already with barely-healed bruises, and to lie down in comfort was such bliss that she nearly wept with gratitude all over again. The noise of the train clattering over the rails, the sound of the engine was muffled to a considerable degree, and the motion rocked her gently, as in a cradle. Other passengers in the Pullman car had already retired, a few still awake, moving in the corridor between heavy curtains drawn for the night, but the small noise of their footsteps, conversation or snoring did not perturb Sophia in the least, or disturb her own slumber, which she fell into almost the moment she rested her head on the pillow. If at some moments she wakened during the night – startled awake by the motion of the train stopping, or starting again, she returned to sleep almost at once.

“I shall always be grateful for the invention of the steam engine,” she told herself, during one of those brief wakeful moments, feeling oddly cheerful. “And to the men who built the railways and Mr. Burton, and George … and to all of them. It will be the train which made an escape from Richard possible, and to get as far away from him as I can be.”

Awakening the following morning was nearly as blissful. For the first time in weeks, she felt quite well. The avuncular porter, George, tactfully guided her those few steps towards the tiny ladies’ sitting room compartment, where she was able to wash thoroughly as was possible and change into fresh clothes – since he thoughtfully had produced her carpetbag from the baggage car. Revived and rested, she felt restored to her own self – the proper and confident Miss Brewer of Beacon Street once again. When she emerged from the sitting room, it was to find the curtains all drawn back, the upper berths tidily folded away, and the lower transformed back into the comfortable settees which they were for the day of travel. Two ladies and a small boy dressed in a rumpled Knickerbocker suit shared the seats: a Mrs. Murray, her son Bertie and her mother, Mrs. Kempton. They greeted Sophia cheerily, obviously seeing her as an agreeable companion for the remainder of the journey. Mrs. Murray was journeying out to Kansas, to join her husband at an Army post there.

“I am Sophie Teague; on my way to Kansas City,” She vouchsafed nothing more than that, always recalling Declan’s warning to not make herself memorable. To her relief, Mrs. Murray and her mother were most incurious about her reasons for traveling, and more inclined to tell her about themselves, and of Colonel Albert Murray’s letters regarding what they might find at Fort Leavenworth.

“We will – if the train runs to schedule – be in Chicago tomorrow morning,” the elder lady assured her. “And then another long day and night to Kansas … Tell me, dear, will you be traveling on from there?”

“I might,” Sophia answered. “It all depends.”

Conductor Burton beamed on her with particular satisfaction, when he passed through on his rounds in mid-morning, and inquired of there were anything he could do for them.

“Better traveling with the other ladies than by your lonesome,” he murmured to her, when she thanked him again. “You never know what might happen, and I’d never forgive myself if it happened on my train, or to you, Miss Teague.” It also occurred to her that anyone observing her with Mrs. Murray and Mrs. Kempton would think they were all of one party.

Another day – this day not weighted with fear and misery – and another night passed, as the train steamed inexorably west, every minute and mile carrying her farther and farther from Boston. She dined with Mrs. Murray and Mrs. Kempton in the railway dining car, as they insisted most emphatically that she share their table. She felt obliged to repay them by amusing little Alfred – who was only six and rather bored with the limited amusements afforded for long stretches of the journey. He reminded her of Richie; frank, fearless and affectionate. Amusing him was a pleasure rather than a duty.

“The countryside is so lovely!” exclaimed Mrs. Murray, as a long vista of lake and meadow opened before them. “A perfect picture! Mama, doesn’t it remind you of some of those panoramic paintings displayed at the Philadelphia Exposition?”

“Store it up in your memory, dear,” Mrs. Kempton advised, “I fear that Kansas will be nothing like this.”

“What is Kansas like?” Sophia’s ears pricked up. If it worked out that she would be hired by Mr. Harvey for work in his railway restaurants, then she might very well be going even farther west than Kansas. Working in some capacity for a railway concessionaire was looking more and more appealing by the moment.

“Flat and full of dust and flies, to hear dear Albert tell it,” Mrs. Kempton replied. “Or at least – that is what he complains of in his letters.”

If true, Sophia thought; Kansas was still a long way from Boston and from a vengeful Richard, who would never – even if he suspected that she were still alive – think to search for her on the wild frontier. And the farther she was from Boston – the safer she would be.

“My dear Miss Teague, have you ever seen such a city?” Mrs. Murray exclaimed in awe, the following morning, as they passed through Chicago. Conductor Barton had assured them, on his most recent perambulation through the car that they would be arriving there very shortly. “And it was burned to the ground not … how many years ago, Mama? And look – now, how splendid the buildings! Such a marvelous hive of industry and commerce; now, if Albert’s duties only kept him here, I would be quite content … save for the smells of the stockyard!” They all coughed, as a sudden throat-closing miasma made itself known on the spring breeze. Mrs. Kempton raised a handkerchief to her nose, and continued, somewhat muffled. “Oh, dear … they say that millions of western cattle are brought here daily to the slaughterhouses of Chicago.”

“Albert wrote about seeing such droves of cattle, being brought north from Texas – so many that the hills were entirely darkened … and the drovers who brought them! As wild as their cattle … just boys, most of them, without a soldierly discipline.”

“They do seem such romantic figures,” Sophia murmured, for young Seamus Teague’s exploration of the wild west had contained many such personages contained within the pages of his dime novels.

“Those are books,” Mrs. Murray tittered. “And there are many such accounts of soldiers, too – and I can assure you – that those tales are just as exaggerated. The realities of life are often romanticized beyond all recognition.”

“I expect that I will see for myself, very soon,” Sophia ventured.

Another night, another day – the country unfolding slowly before them, like the marvelous panorama paintings that Mrs. Murray described. Only this was real rather than the painted simulacrum; meadows blowing with spring wildflowers, the trees adorned with fresh green. The land seemed somehow flatter than what she had been familiar with for so long – as if some giant had pulled the wrinkles out of a counterpane so that it all lay smooth. On the third day since leaving Boston, the train rumbled across a very long iron bridge. The river lay, smooth as silk and seemingly as wide as an ocean.

“That is the Missouri River down there,” Mrs. Kempton said, “We can now say that we are in the west. We’ll be arriving very soon now. Dear Miss Teague; are you being met by friends? You have been such a boon companion; I do not like to think of you, alone and adrift, so far away from home.”

“I have an appointment,” Sophia assured her. “It was for such that I came to Kansas City – an offer of employment.”

“Oh?” It seemed to Sophia that Mrs. Murray’s attitude towards her had chilled a degree or two, and she hastened to reply, feeling a sense of regret. She had been in her proper company for two days and two nights, and now it appeared that she was about to fall from it once more. “I had been as a housekeeper and governess to a distant relation; a situation which did not please me. My cousin’s wife took liberties with my situation, presuming on family loyalties which she would not have dared ask of a hired employee. I thought that I might seek a paid position in a similar capacity. At least – such would be more honest in the exchange of work for pay, rather than no pay and a tenuous social position as an object of charity. ”

“Quite right, my dear,” Mrs. Kempton assured her – most unexpectedly. “Being the object of charity is never comfortable for a young woman of spirit. It would have been seen as scandalous, when I was a girl – but times have changed, and I am assured that it is often quite respectable to expect a wage. Women have talents – interests and abilities outside of marriage – that condition which most assume is all that we have the capability for. I have often thought that a woman ought to have more … choices in the world, and thereby turn to our most natural role as wife and mother with a most willing heart. Have you read the writings of Mrs. Elizabeth Stanton – she is a most particularly outspoken champion of the natural rights of women…”

“Oh, Mama…” Mrs. Murray exclaimed, with a touch of exasperated embarrassment.

“I know of Mrs. Stanton,” Sophia answered, with a feeling of having come all unexpected upon a spring of fresh water in a barren land. “She was a particular friend of my great-aunt Minnie – who also lectured unceasingly on the cause of abolition …”

“It has never ceased to amaze me,” Mrs. Kempton swept over her daughter’s rebuke with a magnificent display of indifference, which reminded Sophia most piercingly of Great-aunt Minnie, “How the full rights of citizens could be invested upon Negro males of suitable years, and yet be withheld from those females of every color and station, who campaigned tirelessly for those same rights. It is as if – the labor of females of every station is only regarded as worthy when it is expended in the cause of every other than our own. To the advantage of men … naturally.”

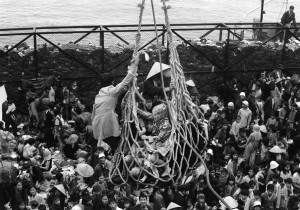

“Mama!” Mrs. Murray protested once again, but there was no time for further discussion, for the train was slowing as it approached the station; here the reverse of departing from Boston, in a tangle of shining steel rails which reminded Sophia of strands of hair, all arranged by the strokes of a comb. The came the metallic shriek of the engine wheels sliding against the rails as the brakes took hold, steam escaping everywhere.

There was a tall man in Army blue waiting on the platform; small Bertie shouted,

“Papa!” as he ran ahead of his mother and grandmother. In a moment, Sophia stood by herself, with her carpetbag in her hand, watching the joyous reunion with wistful eyes. She turned, hearing a respectful cough at her side, to see George, the porter.

“I never get tired of watching folk,” he confessed. “Happy, or sad, eager to travel on, grateful to be home … is there anyone meeting you today, Miss Teague?”

“No,” Sophia replied. “But I do have an appointment, at the office of Mr. Fred Harvey. Can you direct me to it?”

“Mr. Harvey? I don’t know that Mr. Fred Harvey is in town at this moment – he been feeling poorly of late – but Mr. Benjamin most certainly is. The office is in the Annex – I’ll have one of the newsboys show you.” George shook his head, sadly. “This Union Depot is the largest train station outside of New York, they tell me … and one of the most confusing. They call it the Insane Asylum … here, did I say something wrong?” he added, for Sophia had flinched. “They call it that, for the grand muddle that it is – towers on towers and domes on domes, and ornament stuck on every which way. But it’s in the West Bottoms – right handy for freight, but not such a genteel neighborhood, especially not after dark.”

“It is enormous,” Sophie recovered sufficiently to admire the station itself. “And very modern, I think.” What was even more entrancing to her was the sheer purposeful energy of the place, like a kind of lightening which never stopped; constant motion, the near to incessant noise of trains, of barrows of luggage shouldered past by large sweating men in rough clothing, while the newsboys shouted their wares. Steam whistles, the rumble of wheels, half-heard conversations

“It’s the busiest station on this stretch of the river.” George’s uniformed chest appeared to expand with pride. “They say that if you sat in the main hall watching long enough, you’d see anyone of renown in this whole United States. Here now, Miss Teague – if you go out this door, and go along to the telegraph office, you’ll see the sign for the Harvey offices. Are you interviewing to work in one of Mr. Harvey’s places?”

“I am …” Sophia nodded, and to her vague surprise, George looked as though he approved. “I hope …”

“Oh, you’ll be taken on, Miss Teague,” he assured her. “I seen a lot of those Harvey girls at work, and even more who come to interview with Mr. Benjamin and Mr. Harvey. You be just the kind they hire … proper ladies, but willing to work. You’ll do fine. It’s a good job – bed and board, passes to travel for free on the railway – and fine folk to work for, if a mite persnickety. But so’s working for Mr. Pullman. You work for them – well, that’s something to take pride in; you know you are somebody!”

“Thank you, George,” Sophia shifted her carpetbag to her other hand. “For your encouragement and not least for what you have done for me on this journey. I think that I can see where the telegraph office is.”

“You take care now, Miss Teague,” And a broad and merry grin split his face. “See you out on the railway sometime, you hear?”

Recent Comments