Unlike the lawman featured in last week’s installation of ‘rowdy tales of the old west’ this week’s rogue contrived to live a long and eccentric life, and one – considering his reputation – remarkably unstained by deadly street shootouts, outlawry and violent death, although there was the little matter of that horseback duel … the unsuccessful hanging … and that jail escape. Although he was, as noted, a bit of a rogue and a personality to which legends readily attached themselves, often with his encouragement; he ended his days as justice of the peace in the tiny hamlet of Langtry, Val Verde County, Texas – famously the only law west of the Pecos.

Unlike the lawman featured in last week’s installation of ‘rowdy tales of the old west’ this week’s rogue contrived to live a long and eccentric life, and one – considering his reputation – remarkably unstained by deadly street shootouts, outlawry and violent death, although there was the little matter of that horseback duel … the unsuccessful hanging … and that jail escape. Although he was, as noted, a bit of a rogue and a personality to which legends readily attached themselves, often with his encouragement; he ended his days as justice of the peace in the tiny hamlet of Langtry, Val Verde County, Texas – famously the only law west of the Pecos.

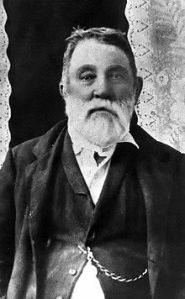

But Phantly Roy Bean had been knocking around the far west for decades before attaining the office for which he is most famed. And yes, that was his real name; his father was also named Phantly – and why he was laden with such a moniker is unknown. In any case, our Phantly Roy ditched the unfortunate first name as soon as possible. He was a Kentuckian who gravitated down river to New Orleans in his mid-teens, got into trouble with authorities there and migrated to San Antonio to work with Sam Bean, an older brother who had worked up a nice business hauling freight after serving in the US Army during the Mexican War. Eventually, the brothers Bean – Roy and another brother, Joshua, followed the Gold Rush to California. Cannily, the brothers Bean did not waste time and energy hunting for gold. Joshua set up a saloon in San Diego, and eventually another one in San Bernardino – but Roy continued to be the scapegrace little brother. There is a pattern here – but he lived long enough to break out of it, at least in a little way.

He was handsome and a snappy dresser, fancied – and fancied enthusiastically in return – by ladies of every nation. He fought a horseback duel with another man in the streets of San Diego, likely over the affections of a local damozel. Both men wounded each other, and startled the town considerably. Bean was arrested, and confined in San Diego’s first proper stone-built jail; the first prisoner confined there, and also the first to escape from it, with the aid of a pair of knives smuggled into him, supposedly concealed in the gift of some tamales from one of his lady admirers. Prudently, Roy moved to San Bernardino to manage the saloon that his brother Joshua had left to him, but trouble followed after, resulting in a duel – again, over the favors of a lady with a rival. This time the other duelist finished up very dead, and at Roy Bean’s hand. Supposedly, several of the rival’s good friends set him on a horse with a noose around his neck and tied to a high branch; only the timely intervention of the woman saved Roy Bean from death by hanging/slow strangulation. In any case, prudence dictated a prompt remove from California. He joined his other brother Sam, in running a saloon and grocery store in a hamlet near Silver City, New Mexico. During the last years of the Civil War, he was working as a teamster again, in San Antonio, hauling cotton to Matamoros, Mexico, to evade the Union blockade.

The post-war years saw him remaining in San Antonio, varying his career by keeping a saloon, and retailing firewood, beef and milk to the good housewives of the area. Alas, the firewood was cut from a neighbors’ wood-lot, the beef also rustled from neighbors; the milk was was adulterated with creek water and when an indignant customer objected to strenuously to the presence of live minnows swimming in the Grade-A, Roy Bean is alleged to have answered that he would stop allowing the cows to drink from the creek. In the first year of peace, Roy Bean took to himself a wife of his own instead of someone else’s. She was Virginia Chavez, a woman not quite half his age, and the marriage was bitterly acrimonious, in spite of (or because of) producing four children. Roy Bean parted from her in the early 1880s and also from San Antonio. A storekeeper in the neighborhood where they had lived was so eager to see Roy Bean gone, that he purchased all of their spare possessions – just so that Bean would have the means of leaving town. Roy separated from his wife, deposited the children with various friends and went west … one more time.

His new enterprise was a saloon in a railway camp in West Texas, which proved to be equally knockabout, until he settled on a permanent location. Typically for him, it was on land that he did not own, on the railroad right of way in Langtry. The railway camps were lawless and rowdy places, with the nearest court of any kind at all being in Fort Stockton, a good two hundred miles away. As appallingly misguided as it seems at first glance (and even on a second), Roy Bean was the nearest available person resembling a solid citizen of fixed abode in the opinion of the local Texas Ranger detachment, who had become wearied with the chore of hauling apprehended miscreants all the way to Fort Stockton. This does bring one to wonder about any of the other candidates. In any case, Roy Bean was appointed as a Justice of the Peace for the district. He held court in his saloon for the larger part of the next two decades, famously advertising himself as the only law west of the Pecos.

For someone who had notoriously trodden well over the side of the law in his day, he didn’t seem to have done too bad a job, given the age and the circumstance. Certainly it satisfied his neighbors, who routinely returned him to office by election until 1896, in spite of his administrative eccentricities. He routinely recessed the court to sell liquor to all present, drafted the barflies present to serve on the jury, and used the butt of his revolver as a gavel. In his rulings from the bench, he was guided only by rough pragmatism and those statutes in the 1879 edition of The Revised Statutes of Texas of which he personally approved. Since he did not have a jail at his disposal, he was at a disadvantage in administering punishments – but never mind. Fines would do; and by interesting coincidence, those fines were always the exact sum of money which the convicted had on him. If the convicted was dead broke, JP Bean’s sentence usually included performing any casual labor needing doing in the district. Only two death sentences were ever handed down in Bean’s court – and one of the condemned promptly escaped. Judge Bean proved adamant concerning turning over the income from fines to the State of Texas, claiming that his court was self-sustaining.

By the end of his life, a large proportion of the fines and the profits from his saloon went to assist the poor and – touchingly – to keep the local public school supplied with firewood. Even without reelection, he continued to administer his eccentric brand of justice until his death in 1903. (From natural causes, I will add.) By then he was a celebrity, and for all of that rather an endearing and relatively harmless one. Certainly, his neighbors thought the world of him. But that is Texas for you.

Recent Comments