Chapter 7 – Fauntleroy’s Woman

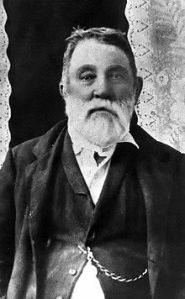

(Arrived in California at last, Fredi Steinmetz – young and wide-eyed and adventurous – has come to the port town of San Diego, with his partner, the mysterious and slightly slippery Polydore A.O’Malley. They have, during a course of sampling the social life available in San Diego, met another slippery character – one Fauntleroy Bean, a gambler with no other visible means of support and a locally shady reputation. Fauntleroy Bean – in later life famous as Judge Roy Bean, the only law west of the Pecos – was in his younger incarnation – slightly less an upholder of law and order. The story continues …)

Fredi sauntered away from the wagon-yard, hands jammed deep in the pockets of his round jacket, his bearing and general air being elaborately casual. He kept to the shadowed side of the street, making his way back to the boarding house, hoping with every step that he had attracted no interest, especially from the Sheriff. He also hoped Sheriff Haraszathy had no abiding interest in turning San Diego upside down, looking for Fauntleroy Bean. It didn’t seem as if there was. What would O’Malley say? Well, Fredi reasoned to himself, they had a promise of payment, for assisting Fauntleroy out of town, and that would be worth something.

At the boarding house, lights glowed from the parlor downstairs. Fredi stole past the doorway on tiptoe and climbed the stairs to the boarder’s room, hoping that O’Malley had returned, and they could make some pretense of speaking privately. To his relief, O’Malley had returned – he lay fully-clothed on top of the blankets, snoring loudly. There was a candle in a metal holder wobbling perilously in a pool of softened wax on the crude wooden wash-stand, the single point of light in the room. They were alone in the room, but for Nipper, curled in his usual neat brindle ball at the foot of the bedstead. Fredi shook his partner’s shoulder, to no avail. The odor of whiskey and tobacco smoke was strong on O’Malley’s clothing and on his breath.

“Wake up, O’Malley,” Fredi begged in a whisper. “Wake up … we’ll have to leave first thing tomorrow. We’ve got paid work, if we go to San Gabriel, first thing… wake up!” He shook O’Malley even more. The other boarders would be coming upstairs any minute.

O’Malley stirred, but only came partially awake. “Freddy lad – let me sleep … I must visit Orla in the morning before I go to Derry.” And then to Fredi’s utter horror, O’Malley began to weep, great shuddering sobs. “Ah, but she is dead, sweet lovely Orla … why did ye do it, Orla? Father Patrick said it was for shame…Dead, all of them, dead and buried …” His voice and the weeping diminished into incoherent mumbling, and then into sleep again, and Fredi sat back on his heels, taken back. O’Malley told many stories along the trail drive, and at the Castillo home-place, but never anything about a woman named Orla, or about leaving one or many dead and buried.

Well, perhaps he could get some sense into – or out of O’Malley in the morning, Fredi concluded. He blew out the candle, undressed as far as his shirt and crawled into bed.

In the morning, O’Malley was little the worse for the evening, only squinting as if the fog-shrouded sunrise made his head hurt. As soon as they were finished breakfast – for which O’Malley appeared to have little appetite – Fredi hustled him away towards the livery stable, Nipper trotting purposefully after.

“We have to leave this morning,” he said, as soon as they were out of any hearing.

“We do, boyo?” O’Malley squinted blearily at him. “I tell you, I was no’ drunk an’ disorderly last night. I did no’ get into a fight, either … Nipper and me, we had a good time, didn’t we, Nip?” He snapped his fingers at Nipper, who now capered alongside them, ears and tail up. If dogs could grin, Nipper was grinning.

“Remember Senor Bean – Fauntleroy Bean, who played cards with us until the sheriff came?”

“Aye – that I do recall… in a haze, but I do recall it. He was no’ supposed to be playing cards, an’ yet he was. The sheriff took him away, didn’t he?”

“Yes,” Fredi decided that short answers were best. “But he escaped from the sheriff – he’s going to have his brother pay us for getting him out of town. I found him hiding in our wagon last night.”

“Oh, did ye now? Is it certain that he will still be there, this foine morning?

“He said he would be,” Fredi answered, his heart lightening. If the elusive and faintly criminal Senor Bean was not in the wagon, then they were free to seek out other employers. “It’s not like we signed a contract or anything…” And Fredi decided that O’Malley might as well know the worst of it. “Likely it’ll be his brother that pays us, rather than him.”

“Oh, Freddy-boyo!” O’Malley looked as if his head pained him even worse. “And if his brother is no’ the least fond of him? What then?”

“Why shouldn’t he pay to get his brother out of trouble?” Fredi demanded, honestly puzzled. “My brother would give the last penny in his pocket for me, if I asked it. Wouldn’t yours?

“No, he wouldn’t.” O’Malley riposted. “Because he had neither pocket nor penny, being a poor Irish cotter lad – and second because he is dead these six years an’ more.”

“Oh,” Fredi considered this startling intelligence. “I’m sorry to hear, O’Malley – indeed I am. On the ship, coming over, was it? My mother and my sister Liesel’s little baby …”

“No,” O’Malley’s voice was curt and sharp, as it almost never was. “Not on ship. Of the Hunger, in Ireland it was. It’s something I’d rather not be reminded of, Fredi-boyo, if ye do not mind.”

“I won’t speak of it again,” Fredi promised. He translated the ‘Hunger’ that O’Malley spoke of into German. Famine, that’s what he meant. Vati had talked it it now and again, for he and his friends sent letters back and forth. The potato crop had failed in many places in the Old Country, of a particularly destructive blight, and if there were no other crop to feed the farm folk with, they would and did starve. Fredi shivered; he had been so long in a bountiful – if sometimes harsh country – that the prospect of having nothing to eat at all was like a frightening story that the older folk would tell.

The livery stable was open at this hour of the morning, a bustle of men, horses, wagons and mules. Their wagon sat by itself in the wagon park behind the stable, canvas cover drawn tight over the contents.

“If our guest is here,” O’Malley said at last. “We shall make ready to hitch the mules. The road to the north is well-marked. The King’s Highway, they call it … I don’t know why, as there has never been a king here. I suppose it was established by the authority of the King of Spain, all this time gone.”

Fredi scrambled up to the wagon-seat and peered inside; there was a great lump of O’Malley’s coachman’s overcoat, with Fauntleroy Bean’s elegant boots sticking out from one end and faint snoring sounds coming from the other.

“He’s here, all right.” Fredi breathed, just as the sleeping form underneath O’Malley’s coat twitched and sat upright, knuckling sleep from bleary eyes.

“Hey, fellows – what kept you this long? Can we get a’moving now?”

“Tell him what you wanted from us,” Fredi demanded. “About your brother and the saloon…”

“The Headquarters in San Gabriel, it’s called – Josh, he’s an officer in the militia, so he named it that.” Fauntleroy Bean yawned, a particularly jaw-cracking yawn. “I don’t have any money save what’s on me, but Josh is good for it. He an’ Sam promised Mama they would always look after me.”

“We do no’ need any excuse to linger, then,” O’Malley snapped his fingers at Nipper, who leapt up to the wagon seat, as nimble as if he had trained for a circus show. “You see to the mules, Fredi-boyo, I’ll pay the liveryman. And how to we find this Headquarters Saloon place, then?”

“Only saloon in town,” Fauntleroy Bean answered, the good cheer of the previous night restored as if by a miracle.

They departed San Diego with some regret, for it had seemed a pleasant and welcoming place to both O’Malley and Fredi. The old King’s Highway led north, near to the coast at first where the gentle salt-smelling breezes fanned them. Gradually the highway veered inland, crossing over a number of tidal salt-marshes, where the reeds grew higher than a man, and rustled in the moving air. Fresh green grasses cushioned the inland hillsides, hillsides which looked as soft as a pillow at a distance. They were dotted with oak trees – gnarled trees which sported small dark green leaves, curled at the edges.

“Another blessed land, never touched by the blighting hand of winter,” O’Malley remarked.

“It’s foggy most days,” Fauntleroy Bean pointed out, from the back of the wagon, lounging like a lord on the stacked bags of flour and beans, cushioned by O’Malley’s overcoat and Fredi’s bed-roll. O’Malley had suggested that he not show himself until they were a fair distance from where anyone from San Diego might recognize him. “And in the winter sometimes, it rains. And rains. For six months a year, you can barely see your hand in front of your face in the mornings. And the winds blow down from the mountains late in summer – it’s like God opened the oven-door of Hell.”

“It cannot be hotter than Texas in the summertime,” Fredi pointed out, and Fauntleroy laughed. “Oh, then you’ll have gotten used to it.”

It took a little more than a week to make a leisurely journey along the old highway – a well-traveled and mostly level road, which uncoiled in wide and lazy bends, only gradually climbing towards the mountains rendered blue in the distance, crowned with white on their very peaks and sometimes shrouded with clouds. They passed through many small towns, the oldest of which had been established by the Spanish, usually coalescing around a mission, like nacre in an oyster-shell. O’Malley marveled at this, and went to every one as they passed, to say his prayers and dedicate a candle.

“’Tis a wonder an’ a delight, Fredi-boyo – to be in a country where the True Church is not slighted.”

“Was it not so in Ireland?” Fredi asked, much curious.

“’Tis better than it once was,” O’Malley replied. Sometimes Fauntleroy Bean accompanied him, although not for purposes of devotion, but to rather flirt with any young women who happened to be about – which mildly annoyed O’Malley. The churches and cloisters were usually very fine – but Fredi noted that much of the orchards, fields and vineyards which once had surrounded the missions had the look of neglect, the vines reverting to their wild nature, and the untended trees dropping wizened olives and citrus fruit onto the ground underneath their branches.

The mission at San Gabriel was one of the largest churches, adorned with a campanile wall, each arched void in it filled with a bell. The building was well-kept, white-washed clean, and the cloister buildings also kept in good steading. It looked as if there were a christening being performed, with the priest in his vestments blessing the parents at the door. As the mules clomped past, Fauntleroy Bean tipped his hat and blew a kiss towards a bevy of handsome young women in bright Mexican silk dresses, the lace veils having from elaborate bone and ivory combs. The ladies giggled, and a young gallant with them scowled in a most threatening way.

O’Malley scowled also.

“Ha’ ye no decency, Faunt’ly? They’re going to confession!”

“That’s where you meet the sweetest and juiciest of them,” Fauntleroy Bean pointed out, utterly unaffected. “Lovely little gardens wherein to put the old Nebuchadnezzar out for a graze… I see it as my duty, giving them something exciting to confess to. And it gives the old padre a thrill as well.”

O’Malley – to Fredi’s mystified astonishment actually looked rather red, especially around his ears. Nebuchadnezzar, out for a graze? What did that mean?

“You’re a heathen, Faunt’ly – of the worst sort. I shouldn’t be surprised to hear that you were killed by a jealous suitor, some day!”

“As long as it happens when I am an old, old man!” Fauntleroy answered, with a jaunty air. “Ah – there is the Headquarters Saloon – Brother Josh’s home away from home – present your bill, boys, for Josh will serve up the fatted calf, for certain!”

Recent Comments