His name wasn’t really Mickey Free, and he wasn’t really an Apache Indian. The legendary Al Sieber, chief of Army scouts in the badlands of the Southwest after the Civil War once described him as ‘Half Mexican, half Irish and whole S-O-B.’ Mickey Free was one of Sieber’s scouts, enlisted formally into the US Army in the early 1870s at Fort Verde, Arizona, eventually rising to the rank of sergeant. He was a valuable asset to Sieber and the Army as a scout and interpreter as he was fluent in English, Spanish and the Apache dialects. Most observers assumed that Mickey Free was at least half-Apache, though. He raised a family, served as a tribal policeman and when he died, was buried at his long-time home on the reservation of the White Mountain Apache. But he was just as Al Sieber had said – Mexican and Irish – and his birth name was Felix Martinez. And what many didn’t know was that Mickey Free was entangled inadvertently in the bitter and ongoing war between the Apaches and the whites long before his enlistment in the Army.

His name wasn’t really Mickey Free, and he wasn’t really an Apache Indian. The legendary Al Sieber, chief of Army scouts in the badlands of the Southwest after the Civil War once described him as ‘Half Mexican, half Irish and whole S-O-B.’ Mickey Free was one of Sieber’s scouts, enlisted formally into the US Army in the early 1870s at Fort Verde, Arizona, eventually rising to the rank of sergeant. He was a valuable asset to Sieber and the Army as a scout and interpreter as he was fluent in English, Spanish and the Apache dialects. Most observers assumed that Mickey Free was at least half-Apache, though. He raised a family, served as a tribal policeman and when he died, was buried at his long-time home on the reservation of the White Mountain Apache. But he was just as Al Sieber had said – Mexican and Irish – and his birth name was Felix Martinez. And what many didn’t know was that Mickey Free was entangled inadvertently in the bitter and ongoing war between the Apaches and the whites long before his enlistment in the Army.

He was born in Santa Cruz, Sonora, the son of Jesusa Martinez and Santiago Tellez, who was said to be Irish, or part Irish. When Santiago Tellez died, Jesusa married John Ward, and took her small son to live on Ward’s small ranch on Sonoita Creek, southeast of Tucson. Sonoita was very much out of the way – and even more so late in 1860 or early 1861, when John Ward’s ranch was raided by a party of Arivaipa Apaches bound on stealing stock. Felix Martinez, then about twelve years old was captured and taken also; some accounts have it that he tried to climb up into a fruit tree to hide. But he was captured anyway – and taken away by the raiders. Other accounts have it that Felix’s stepfather was more concerned about the loss of his cattle than the boy, and only belatedly demanded the return of both. Some months later, the officer commanding at the nearest Army post, Fort Buchanan ordered a detachment of soldiers to go out with John Ward and an interpreter, towards the area around Apache Pass. It was supposed that the boy and the stolen cattle were there, in the area where the Overland Mail stage road passed through the mountains. The military detachment was under the command of a young and fairly recent West Point graduate, one Lt. George Bascom, who was later charitably described as an officer, a gentleman … and a fool.

Near the Apache Pass stage station, Bascom and his party encountered the Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise. Bascom asked for a meeting in a council tent with Cochise, and began it badly by demanding return of the boy and the stolen stock. Cochise answered honestly and fairly; he did not have them – but given time, he promised to find out who did and return them. Up until that very day, Cochise had been friendly and conciliatory to whites; indeed, the Overland Mail stages only operated because Cochise and his warriors allowed it. Bascom arrogantly repeated his demand for immediate return of the boy Felix – and informed Cochise that he and his party would be held hostage against the boy’s return. Bascom’s soldiers had been instructed previously to take Cochise and his party prisoners but Cochise had a knife. In the ensuing fracas, he slashed his way free, although his companions – including his own brother and two nephews – were captured. Bascom took his Indian hostages back to the shelter of the Apache Pass stage station. Meanwhile, Cochise and his warriors attacked an American supply train and captured three hostages, offering them to Bascom in exchange for his brother and nephews. Bascom refused – he would accept only Felix Martinez and the stolen cattle for Cochise’s relatives. Cochise killed his captives, before escaping into the Sonora – and Bascom hanged his, before returning to Fort Buchanan. The war by Apache on the Federal Army and the white settlers of Arizona was on … and very shortly to be joined by the greater civil war between the Union and the Confederacy. In all of that bloody conflict, the matter of 12-year old Felix Martinez Ward was shelved. It is entirely likely that only his mother cared very deeply; his stepfather didn’t seem to, the military commander in the region soon had bigger problems, and Lt. Bascom was killed in battle at Val Verde, New Mexico territory the following year. The Martinez-Ward family seems to have concluded that the boy was dead, or gone far beyond reach, although a half-brother was surprised many years later to discover the truth.

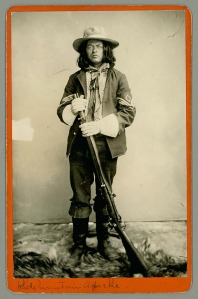

So, what happened to Felix Martinez Ward? Pretty much what happened to many Anglo and Mexican boys of a certain age taken captive by the Tribes. He was adopted into the White Mountain Apache tribal division – treated with relative kindness and trained in the traditional ways. And eleven years after his abduction from his stepfathers’ ranch, Felix Martinez Ward enlisted in the US Army as an Apache scout under the name Mickey Free. He participated in the US Army’s campaign to capture the last stubborn Apache band led by Geronimo – and there exist many pictures of him, either alone or with the other Apache scouts. He is fairly easy to pick out from a group, for although he has long, thick hair to his shoulders … he has a rather round face, with a snub nose and a cleft in his chin. He does not look Indian in the least. Put him into the chorus line of Riverdance, and he’d blend right in.

He lived to a ripe old age on the White Mountain Reservation, and was buried there, leaving many descendants.

Recent Comments