During our last summers overseas, my daughter and I took to camping on our vacations, as the most economical way of traveling and seeing as much of the country as we could. A nice campground in Spain provided the convenience of a hotel at a fraction of the cost, and for a child, the chance to run and romp freely. Guided by a copy of the “guia”, which listed the campgrounds in proximity to various cities, and icons indicating what sort of comforts were provided— pool, shop, hot showers, electricity— and where (km 320 N, carretera # so and so) one summer trip described a large loop through Extremedura, Andalucia and Granada. Blondie’s only dictate about our camping place concerned the availability of either a pool, the sea, or in a pinch, a river in which to frolic. She swam like a fish, and preferred to spend as much time as possible in a bathing suit.

During our last summers overseas, my daughter and I took to camping on our vacations, as the most economical way of traveling and seeing as much of the country as we could. A nice campground in Spain provided the convenience of a hotel at a fraction of the cost, and for a child, the chance to run and romp freely. Guided by a copy of the “guia”, which listed the campgrounds in proximity to various cities, and icons indicating what sort of comforts were provided— pool, shop, hot showers, electricity— and where (km 320 N, carretera # so and so) one summer trip described a large loop through Extremedura, Andalucia and Granada. Blondie’s only dictate about our camping place concerned the availability of either a pool, the sea, or in a pinch, a river in which to frolic. She swam like a fish, and preferred to spend as much time as possible in a bathing suit.

The nearest campground to Seville was several miles distant inland from the city, a dusty tract on a frontage road paralleling the autopista between Cordoba and Seville, grown with trees, and scrub brush, stretching uphill from the entrance. The main permanent buildings were clustered around a pool at the bottom end: a bar with a little restaurant, the managers office, a little store selling small propane bottles, soft drinks, bread and canned goods. A narrow paved roadway zigzagged up the hill, past the pool and bar, past clusters of tent sites and parking places, leveled out of the hillside here and there, looped around the top of the property, where the washrooms and showers, and the water spigots and sinks for doing dishes crowned a little, rocky knoll, and meandered down again on the opposite side. Since it was not actually the holiday season— the month of August— for Spaniards, the campground was all but deserted, and the restaurant not yet open for business. There were a couple of families with caravans on the electrified campsites, lower down the hill, and a couple from Holland on the site next to ours, tent-camping.

My daughter and I had gotten very adept at setting up the tent, and the little gas stove with our cooking pots. We had a couple of folding chairs, and an ice-box, and managed very efficiently, cramming it all into the Very Elderly Volvo’s generous trunk and moving on, ever couple of days— unlike the Spanish, who set up elaborate tent-cottages at some salubrious spot for the month of August, and brought along refrigerators, televisions, pets and all. We had seen cats, birds, dogs, and even a pair of monkeys at a campground near Leon, but the campground in Seville took the cake, because there was a horse.

We came up from the pool, early in the evening, walking up the dusty footpath towards our tent, and there was a man on a dapple-gray horse, exercising the horse among the trees at the upper end of the campground. The man was a wiry little guy, in jeans and a short-sleeved shirt, missing half the buttons, and a soft cap pulled over his eyes. The horse was a dainty thing, several hands shorter than Wilson, the horse that Mom and Dad had bought for us to learn to ride, with an elegantly dark gray muzzle, hard-muscled and sleek. My daughter was enchanted, and eaten up with curiosity. The rider as well as the horse were very much dressed down: the light saddle was worn, and the bridle was held together at some points with knots of plastic string, while the rider slouched through some paces, and briefly struck a pose you see in pictures; reins in one hand, fist on hip; glorious, martial and Spanish to the core. Then he waved to us, casually.

“’Ola… como ‘stas.”

“Buenos,” I said with the proper Aragonese slur. “Habla englis? Habla un poco espanol.”

“Si.” He rode up to us, as my daughter asked,

“Can I pet the horse?”

“Si. “ He affectionately slapped the horses’ neck, and it dipped a velvety muzzle to us.

“Mind the teeth,” I said to my daughter. I rubbed the flat part, above the nostrils, and the horse blew out an alfalfa-scented gust, “Pet the dark parts… doesn’t that feel like velvet.” Her eyes were huge. The rider swung down, still holding the reins in one hand, and we began to talk. I cannot now remember sure exactly how the conversation went, only that it was in a combination of fractured English and Spanish. He gave us to understand that the horse was a mare, in foal (he slapped her barrel gently) and that he had been at an equestrian event in Seville. His good friend was the bartender at the campground bar, and his wife was coming tonight with a horse trailer, but he was killing time until then. He had a finca (a ranch) several hours away, and the mare was a proper bull-fighting horse. He proudly pointed out a healed scar on her shoulder, and casually asked if either of us would like to ride for a bit. I demurred, as it had been a good many years since Wilson, and I had been more used to riding without a saddle, but my daughters’ eyes got huge with excitement,

“Si, por favor!” she breathed.

I held the reins, while he gave her a leg up, and showed her how to put her toes into the stirrups. She had only once been on a horse, and twice on donkeys, all three times while someone led the animal around. He handed her the reins, and showed her how to use them to control the horse, while I watched apprehensively as she pulled too far back, and the mare began to rear. Both of us dove for the mare’s nose, while my daughter stuck like a burr to the saddle, not the least bit frightened or out of countenance.

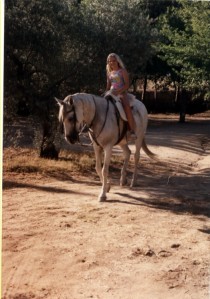

I let out my breath… my god, she was at home as if she had been born in a saddle and ridden every day of her life. She sat proud and fearless, all of ten years old, while the mare’s owner jovially called out a reminder to keep her elbows in. She nudged the mares’ flanks with her heels, and the mare obediently walked ahead— no gentle old plug kept for a children’s easy ride, but a working, bullfighting horse, but then she had ever been the most fearless of children: not heights, not barking dogs, not strangers or the deepest of water had ever held terror for her.

She rode that horse all over the upper part of the campground for two hours, at a walk, trot, even essaying a short gallop or two, while the Dutch couple and I watched, and the mare’s owner kept company with us. We all drank sangria in the twilight and talked in English and Spanish about horses, and what we had seen in Spain, and where we lived. Occasionally, as my daughter went by on the dapple mare, he called out encouragement and praise, and reminders about keeping elbows in and heels down, and I wondered where on earth and by what genetic predilection this skill had come from, appearing in full flower. People are not supposed to be instantly good at something, this was like watching a kid go to a piano for the very first time, and belt out a Goldberg Variation, or diagram an obscure and complicated mathematical theory the first time they pick up a piece of chalk… but there she was, instantly at ease, better than I had been after weeks of lessons.

Where are those talents hidden, and how many revealed by an unexpected coincidence? How often does this happen with parents, watching their children suddenly take to the air and fly on the wings of that talent, while we stand on the ground and watch. For me, it was that time in a campground in Spain, when my daughter took the reins of a bullfighting horse, and never once looked down.

Recent Comments