When gold was discovered in the foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada in 1848, it didn’t take very long for word to get out. From the eastern United States, California was then a six-month journey by mule trail or covered wagon over land – that or a long sea voyage around South America, or two sea voyages broken by a short but disease-plagued trek across the narrowest part of Central America. The sea voyage was expense, the overland journey a bit less so – and it probably seemed much more direct, anyway. Two young Gold Rushers who hit the trail in the spring of 1849 were William Manly and John Rogers; young and adventurous single men who had come by separate means as far as Salt Lake City. Manly already had an adventurous trip just getting that far. From an account written much later, he seems to have been a broad-minded optimist, good-humored and above all – and adventurous. He and some companions had decided to venture down an uncharted river in canoes – and only an encounter with some helpful Indians prevented them from going all the way – down an uncharted river and into a deep and impassible canyon. With one thing and another, they had arrived too late in the season to consider crossing the Sierras by the Truckee River Pass. This was three years after the Donner Party – which served as a Dreadful Warning to all wagon train parties considering a mountain passage late in the trail season.

Instead, Manly and Rogers hired on as drovers or general hands to a lately-arrived party of emigrants and gold seekers who had sensibly decided to follow what was known as the Old Spanish Trail, which led south from Salt Lake City and then west to Los Angeles; the present-day IH-15 roughly follows this trail. The leaders of the so-called Bennett-Arcane party didn’t want to risk any more peril for their families than they had already. The Old Spanish Trail did cross some considerable stretches of desert, but there were regular sources of water all the way along, and it was quite well-traveled.

Unfortunately, the Bennetts and the Arcanes and their friends were tempted into taking a short-cut – the bane of early wagon train pioneers, and one which usually contributed considerable hardship, if not to their doom. They had a map from a fellow in Salt Lake City who was represented as an expert geographer. As it turned out, he wasn’t – and the seven wagons of the Bennett-Arcane party went off the trail and into an endless and trackless stretch of desert, a valley broken here and there by ranges of steep mountains. By the end of November, 1849, they were across the valley – but nearly out of supplies and had butchered most their draft oxen as they failed, one by one. Fortunately, they had found a small freshwater spring. From there they decided to send for help – and William Manly and John Rogers volunteered … to set out on foot, with only what they could carry. Decades later, Manly set down an account of that journey. “… Mr. Arcane killed the ox which had so nearly failed, and all the men went to drying and preparing meat. Others made us some new mocassins out of rawhide, and the women made us each a knapsack. Our meat was closely packed, and one can form an idea how poor our cattle were from the fact that John and I actually packed seven-eighths of all the flesh of an ox into our knapsacks and carried it away. They put in a couple of spoonfuls of rice and about as much tea … the good women said that in case of sickness even that little bit might save our lives. I wore no coat or vest, but took half of a light blanket, while Rogers wore a thin summer coat and took no blanket. We each had a small tin cup and a small camp kettle holding a quart … They collected all the money there was in camp and gave it to us. Mr. Arcane had about $30 and others threw in small amounts from forty cents upward. We received all sorts of advice. Capt. Culverwell was an old sea faring man and was going to tell us how to find our way back …” There was no need for that; Mr. Bennett had utter faith in Manly’s ability to find his way out of the valley and back.

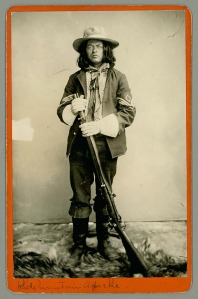

Rogers had a single shotgun, and Manly borrowed a repeating rifle.They set bravely out, not knowing that they would have to walk 250 miles through the desert before reaching aid. They found the occasional spring of sweet water, but others were contaminated with alkali or salt. “ … Our mouths became so dry we had to put a bullet or a small smooth stone in and chew it and turn it around with the tongue to induce a flow of saliva. If we saw a spear of green grass on the north side of a rock, it was quickly pulled and eaten to obtain the little moisture it contained … Our thirst began to be something terrible to endure, and in the warm weather and hard walking we had secured only two drinks since leaving camp… We tried to sleep but could not, but after a little rest we noticed a bright star two hours above the horizon, and from the course of the moon we saw the star must be pretty truly west of us. … The thought of the women and children waiting for our return made us feel more desperate than if we were the only ones concerned. … I can find no words, no way to express it so others can understand. The moon gave us so much light that we decided we would start on our course, and get as far as we could before the hot sun came out, and so we went on slowly and carefully in the partial darkness, the only hope left to us being that our strength would hold out till we could get to the shining snow on the great mountain before us. We reached the foot of the range we were descending about sunrise. There was here a wide wash from the snow mountain, down which some water had sometime run after a big storm, and had divided into little rivulets only reaching out a little way before they had sunk into the sand.”

With the shotgun and repeating rifle, they were able to hunt for food along the way, but Manly suffered from an injury to one of his legs and could only limp along slowly. He urged Rogers to go ahead alone, Rogers refused, so they went on together. On the last day of December, the two young men finally arrived at Mission San Fernando. With the money they carried, they bought two horses, a mule and sufficient supplies … and returned the way they had come. They had to abandon the horses halfway back, but the mule with the precious supplies was as nimble-footed as a cat on the most treacherous part of their passage. They arrived to find their friends all alive but one; Capt. Culverwell, the seafaring man. The life-saving journey took them twenty-six days, there and back. The Bennetts and Arcanes packed up those valuables left to them on the backs of their surviving oxen and the nimble-footed mule and walked out. Years later, Manly wrote of the adventure which had tried them all to extreme: “There were peaks of various heights and colors, yellow, blue fiery red and nearly black. It looked as if it might sometime have been the center of a mammoth furnace. I believe this range is known as the Coffin’s Mountains. It would be difficult to find earth enough in the whole of it to cover a coffin. Just as we were ready to leave and return to camp we took off our hats, and then overlooking the scene of so much trial, suffering and death spoke the thought uppermost saying:—”Good bye Death Valley!”

The spring where the party had camped, waiting for the young men’s return is still called Bennett’s Well. It’s at the foot of the Panamint Mountains. Ironically, fifty years later, Death Valley itself would be the focus of the last of the great western gold and silver rushes.

(Manly’s account, Death Valley in 49 is available as a free eBook from Project Gutenberg, and it is a surprisingly lively read.)

Recent Comments