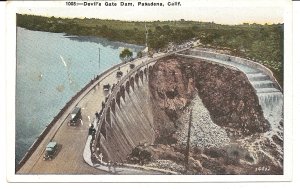

I have a shoebox full of vintage postcards, collected in the Thirties by the invalid young son of Grandpa Jim’s employer. Among my favorite cards are those of places I knew, like the Devil’s Gate Dam, on the nebulous border between La Crescenta and Pasadena, with a Model-A Ford on the roadway atop the dam, and Mt. Wilson topped with snow in the background, and a view of the Arroyo Vista hotel, still a landmark in the days when Mom was driving us to Pasadena to visit the grandparents, but half a century past its Roaring Twenties prime.

My very favorite is a view again of Mt. Wilson and the San Bernardino range, edged with snow against a turquoise blue sky, and acres of orange groves covering the entire plain below, even up to the foothills. From the mountain peaks and ridges, an expert could deduce where that particular vista had been taken down for 3-penny posterity. The citrus groves were long gone from Pasadena when I was a child, nibbled away by suburbia, but pockets of hold-outs still held sway in back yards; Grannie Jessie and Uncle Jim had an enormous lemon tree in their front yard, and a smaller orange tree along the driveway, shading the only place where JP and I were allowed to dig, and make mud pies amid the sweet scent of orange blossoms and the still-sweet moldy smell of the windfalls.

When Grandpa Al and Grannie Dodie first moved out to Camarillo in the early 1960ies, and Mom and Dad would drive up on Saturday afternoons for dinner, the way there from the Valley that was not rolling hills covered in tawny dry grass and dark green live-oaks, was still taken up with citrus groves. The orchards were like vast, roofless rooms, walled with the windbreak trees, and floored in neat rows of orange, lemon and grapefruit trees, guarded by tall towers with slow-moving vanes intended to move the air when it came too close to freezing.

Gradually, creeping fingers of suburbia reached into the groves along the highway, just as they had before in Pasadena and the San Fernando Valley. Between one Saturday dinner and the next, the grove was bulldozed and by the next year, there would be a tract of houses, and the windbreak around the grove would be ragged, no longer a tall, sheltering wall against the wind. No doubt a few survivor trees lingered in back yards, or maybe were planted by the builders. Redwood House was built on hills which had once been olive groves, and the surviving trees still aligned in rows, along the roads or from yard to yard, but someone had planted orange and lemon trees there, and around Hilltop House. After we moved in, Dad averred that he had favored buying it because he had a wish to have fresh-made lemonade from fresh-picked lemons from his own tree on the Fourth of July.

Oranges and lemons were so ubiquitous, so much a part of the public and private landscape that it came as a shock to realize there were people elsewhere who had to go to the store and actually buy them… and they were an exotic and foreign delicacy at that. Our neighbors at Hilltop House brought over their visiting English cousins, so their children and their little cousins could swim in the pool— three little boys who looked like various incarnations of the juvenile Roddy McDowell. The youngest happened to notice the orange tree, growing in the hillside by the steps to the pool.

“What is that, miss? A peach tree?”

“No, it’s an orange tree, “ I said, and his eyes widened.

“May I have one, miss?” he asked, tremulously, “To eat?”

“You can pick many as you like,” I said, and damned if he didn’t sit down and eat four of them.

Feeling a little guilty over the fruit that fell from the tree and was wasted, Pippy and I made a concerted effort to keep ahead of production, that summer. We filled three or four shopping bags with ripe oranges, without making an appreciable dent in the bounty. It was more than we and our neighbors could ever eat, so we converted it into juice. Gallon jugs of juice filled the refrigerator— still more than we could drink, and before we could think of what to do with it all, the brush at the end of the hill caught fire, and we would up taking it out to the firemen afterwards. They drank it gratefully every drop, straight from the jugs, fresh-pressed and icy cold on a hot day after a brushfire. So much for trying to keep ahead of the bounty, but we could not count on a fire every day.

We went back to letting the surplus rot on the ground, but at least our bees got the good out of it. Amidst the other pets, strays and lab survivors and Hilltop House, we had taken on a hive of bees. Our pastor’s oldest son had begun working on a Scout Merit Badge in beekeeping, and alas, too late, discovered that he was one of those severely allergic to bee stings. The hive had to go, and go it did, with all the paraphernalia, to the sunny hillside above the vacant lot next door, which was planted in thyme and native chaparral. For two or three years, we had our own honey.

We never did figure out what plants the bees favored, because the honey was like nothing else I have tasted since. It was clear, almost like Karo syrup, with a delicate flavor, not quite citrus, not thyme, distinctive, but unidentifiable, as rare as the oranges were common.

Oranges and honey, tart and sweet, enduring, but ephemeral, a vision of California that still exists in the backyards of suburbia, and on the postcards from another era.

Recent Comments