That is just what it was, when the building which is the premier landmark in San Antonio – and perhaps all of the rest of Texas – first achieved fame immortal, in the short and bloody space of an hour and a half, just before sunrise on a chill spring morning in 1836. People who come to visit today, with an image in their mind from the movies about it – from John Wayne’s version, and the more recent 2004 movie, or from sketch-maps in books about the desperate, fourteen-day siege are usually taken back to discover that it is so small. So I know, because I thought so the first time I visited it as an AF trainee on town-pass in 1978. And it is small – one of those Spanish colonial era buildings, in limestone weathered to the color of dark ivory. That chapel is only a remnant of a sprawling complex of buildings. Itself and the so-called ‘Long Barracks’ are the only things remaining of what was once called the Mission San Antonio de Valero, given it’s better known appellation by a company of Spanish cavalry stationed there in the early 19th century – they called it after the cottonwood trees around their previous station of Alamo de Parras, in Coahuila. It was the northernmost of a linked chain of five mission complexes, threaded like baroque pearls on a green ribbon, and originally established to tend to the spiritual needs and the protection of local Christianized Indian tribes. The missions were secularized at the end of the 18th century, the lands around distributed to the people who had lived there. Their chapels became local parish churches – while the oldest of them all became a garrison.

That is just what it was, when the building which is the premier landmark in San Antonio – and perhaps all of the rest of Texas – first achieved fame immortal, in the short and bloody space of an hour and a half, just before sunrise on a chill spring morning in 1836. People who come to visit today, with an image in their mind from the movies about it – from John Wayne’s version, and the more recent 2004 movie, or from sketch-maps in books about the desperate, fourteen-day siege are usually taken back to discover that it is so small. So I know, because I thought so the first time I visited it as an AF trainee on town-pass in 1978. And it is small – one of those Spanish colonial era buildings, in limestone weathered to the color of dark ivory. That chapel is only a remnant of a sprawling complex of buildings. Itself and the so-called ‘Long Barracks’ are the only things remaining of what was once called the Mission San Antonio de Valero, given it’s better known appellation by a company of Spanish cavalry stationed there in the early 19th century – they called it after the cottonwood trees around their previous station of Alamo de Parras, in Coahuila. It was the northernmost of a linked chain of five mission complexes, threaded like baroque pearls on a green ribbon, and originally established to tend to the spiritual needs and the protection of local Christianized Indian tribes. The missions were secularized at the end of the 18th century, the lands around distributed to the people who had lived there. Their chapels became local parish churches – while the oldest of them all became a garrison.

There is a birds-eye view map of San Antonio drawn and published in 1873, a quarter century after the last stand of Travis and Bowie’s company that shows a grove of trees in rows behind the apse of the old chapel building. In the year that the map was made, the chapel and the remaining buildings were still a garrison of sorts – an Army supply depot, and the plaza in front of it a marshaling yard. One wonders if any of the supply sergeants of that time or any of the laborers unloading the wagons bringing military supplies up from the coast and designated for the garrison gave a thought to the building they worked in. Did they think the place was haunted, perhaps? Did they hear whispers and groans in the dark, think anything of odd stains on the floors and walls, of regular depressions in the floor where defensive trenches had been dug at the last? What did they think, piling up crates, barrels and boxes, in the place that the final handful of survivors had made their last stand, against the tide of Santa Anna’s soldiers flooding over the crumbling walls?

There is a birds-eye view map of San Antonio drawn and published in 1873, a quarter century after the last stand of Travis and Bowie’s company that shows a grove of trees in rows behind the apse of the old chapel building. In the year that the map was made, the chapel and the remaining buildings were still a garrison of sorts – an Army supply depot, and the plaza in front of it a marshaling yard. One wonders if any of the supply sergeants of that time or any of the laborers unloading the wagons bringing military supplies up from the coast and designated for the garrison gave a thought to the building they worked in. Did they think the place was haunted, perhaps? Did they hear whispers and groans in the dark, think anything of odd stains on the floors and walls, of regular depressions in the floor where defensive trenches had been dug at the last? What did they think, piling up crates, barrels and boxes, in the place that the final handful of survivors had made their last stand, against the tide of Santa Anna’s soldiers flooding over the crumbling walls?

Probably not much– whitewash covers a lot. And a useful, sturdy building is just that – useful. By the 1870s, those Regular Army NCOs working in there were veterans of the Civil War, and perhaps haunted enough by their own war, just lately over. The growing city had spread beyond those limits that William Travis, David Crocket and James Bowie would have seen, looking down from those very same walls.

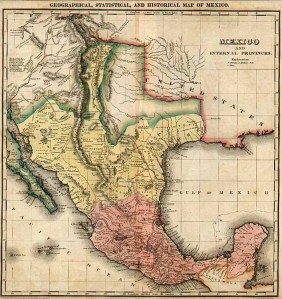

In 1836 that cluster of buildings, and the old church with it’s ornate niches and columns twisted like lengths of barley sugar sat a little distance from the outskirts of the best established provincial town in that part of Spanish and Mexican Texas, out in the meadows by a loop of clear, narrow river fringed by rushes and willows. San Antonio de Bexar, mostly shortened then to simply “Bexar”, was then just a close clustered huddle of adobe brick buildings around two plazas and the stumpy spire of the church of San Fernando. It is a challenge to picture it, in the minds eye, to take away the tall glass buildings all around, the lawns and carefully tended flowering shrubs, to ignore the sounds of traffic, the SATrans busses belching exhaust, and see it as it might have appeared, a hundred and sixty years ago. I think there would have been cottonwood trees, close by. Thirsty trees, they plant themselves across the west, wherever there is water in plenty, their leaves trembling incessantly in the slightest breeze. There might have also have been some fruit orchards planted nearby – the 1873 map certainly shows them. But otherwise, it would have been open country, rolling meadows star-scattered with trees, and striped across by two roads; the Camino Real, the King’s road, towards Nacogdoches in the east, and the road towards the south, towards the Rio Grande. In the distance to the north, a long blue-green rise of hills marks the edge of what today is called the Balcones Escarpment. It is the demarcation between a mostly flat and fertile plain which stretches to the Gulf Coast, and the high and windswept plains of the Llano, haunted by fierce and war-loving Indians. This is the place where three very different men came to, in that fateful year that the Texians rebelled against the rule of the dictatorship of what the knowledgeable settlers of Texas called the “Centralistas” – the dictatorship of the central government in Mexico City.

In 1836 that cluster of buildings, and the old church with it’s ornate niches and columns twisted like lengths of barley sugar sat a little distance from the outskirts of the best established provincial town in that part of Spanish and Mexican Texas, out in the meadows by a loop of clear, narrow river fringed by rushes and willows. San Antonio de Bexar, mostly shortened then to simply “Bexar”, was then just a close clustered huddle of adobe brick buildings around two plazas and the stumpy spire of the church of San Fernando. It is a challenge to picture it, in the minds eye, to take away the tall glass buildings all around, the lawns and carefully tended flowering shrubs, to ignore the sounds of traffic, the SATrans busses belching exhaust, and see it as it might have appeared, a hundred and sixty years ago. I think there would have been cottonwood trees, close by. Thirsty trees, they plant themselves across the west, wherever there is water in plenty, their leaves trembling incessantly in the slightest breeze. There might have also have been some fruit orchards planted nearby – the 1873 map certainly shows them. But otherwise, it would have been open country, rolling meadows star-scattered with trees, and striped across by two roads; the Camino Real, the King’s road, towards Nacogdoches in the east, and the road towards the south, towards the Rio Grande. In the distance to the north, a long blue-green rise of hills marks the edge of what today is called the Balcones Escarpment. It is the demarcation between a mostly flat and fertile plain which stretches to the Gulf Coast, and the high and windswept plains of the Llano, haunted by fierce and war-loving Indians. This is the place where three very different men came to, in that fateful year that the Texians rebelled against the rule of the dictatorship of what the knowledgeable settlers of Texas called the “Centralistas” – the dictatorship of the central government in Mexico City.

That most northern, fractious and rebelliously-inclined of those northern provinces of the nation of Mexico was in ferment in the 1830s, some of which might be chalked up to the presence of settlers who had come to Texas from the various United States looking for land. Texas had plenty of it to go around, and a distinct paucity of residents. Entrepreneurs, such as Stephen Austin’s father were allotted a tract of land, based upon how many people they might induce to come and settle on it, to build houses and towns, businesses and roads. All they need to do was to swear to a new allegiance – initially to the King of Spain, later to the Mexican government, which was making tentative and eventually unsuccessful efforts to model itself after the United States’ experience in democracy. Oh, and convert to Catholicism, at least on paper, although most American settlers were assured that they would be left alone thereafter, as afar as matters religious.

Texas was thinly settled, and a long, long way from the seat of authority in Mexico City anyway. So, Americans trickled in over two decades; undoubtedly many like Stephen Austin were honestly grateful for the free land and consideration from the Mexican authorities, and initially had no thought of trafficking in rebellion. Probably equal numbers of Americans did have an eye on the main chance in coming to Texas, as the initially small and poor United States spilled over the Appalachians, purchased a great tract of the continent from the French, and began to think it was their unique destiny to reach from sea to shining sea.

But the land drew them – and it was a beautiful, beautiful place, that part of Texas that forms the coastal plain. Wooded in the east, in the manner that the American settlers were accustomed to, crossed and watered by shallow rivers, a country of gently rolling meadows and hills, fairly temperate, especially in comparison to more northerly climes. Winters were mild – there was not the snow and brutal cold that forced a three or four month long halt to all agricultural and herding pursuits. The sky seemed endless, a pure clear blue, with great drifts of clouds sailing through it.

And so three men came to Texas in the 1830s, three men of different backgrounds and experience, and all of them looking for a second chance after various personal, political and business screw-ups. One more thing had they in common – they all died on a dark March morning in a single place, within the space of an hour or so.

James Bowie was the one who came first; a hot-tempered roughneck with a series of distinctly shady business dealings in his immediate past – which included slave-smuggling and real-estate fraud. He was famous for the wicked-long hunting knife which he always carried, after a particularly bloody brawl in which he had been armed with a clasp knife, which he opened with his teeth (losing one in the process) while gripping his opponent one-handed. A charismatic scoundrel, a bad-hat, a violent man, occasionally given to moments of chivalry; he does not come across as someone whose company would have been totally pleasant. It might aptly be said of him, as it was of Lord Byron, he was ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’.

James Bowie was the one who came first; a hot-tempered roughneck with a series of distinctly shady business dealings in his immediate past – which included slave-smuggling and real-estate fraud. He was famous for the wicked-long hunting knife which he always carried, after a particularly bloody brawl in which he had been armed with a clasp knife, which he opened with his teeth (losing one in the process) while gripping his opponent one-handed. A charismatic scoundrel, a bad-hat, a violent man, occasionally given to moments of chivalry; he does not come across as someone whose company would have been totally pleasant. It might aptly be said of him, as it was of Lord Byron, he was ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’.

William Barrett Travis was the second; almost a generation younger, but driven by similar impulses, grandiose ambitions, and with an ego almost as big as Texas itself. He would also not have been very good company, laboring as he did under the conviction that he was meant to do great things. Moody and impulsive, somewhat hot-tempered, he had come to Texas alone, abandoning a wife and two children and set up a law practice in Anahuac, the official port of entry for Texas. He drifted into a faction opposed to the Mexican rule of Texas, and in contention with the local Mexican authorities.

William Barrett Travis was the second; almost a generation younger, but driven by similar impulses, grandiose ambitions, and with an ego almost as big as Texas itself. He would also not have been very good company, laboring as he did under the conviction that he was meant to do great things. Moody and impulsive, somewhat hot-tempered, he had come to Texas alone, abandoning a wife and two children and set up a law practice in Anahuac, the official port of entry for Texas. He drifted into a faction opposed to the Mexican rule of Texas, and in contention with the local Mexican authorities.

Davy Crockett – who rather preferred to be known as David Crockett, as a gentleman, rather than as a simple, blunt-spoken frontiersman — was in his lifetime the most famous of the three, and also a latecomer to Texas. A politician and a personality, he was a restless spirit, never quite entirely content with where he was, or what he was doing for long. One senses that he would have been the most congenial of the three: relatively soft-spoken, adept with words – a skilled politician. He played the fiddle, and probably did not wear a coonskin cap or a fringed leather jacket; he looks quite the polished, genteel and well-dressed gentleman in the best-known portrait of him, in high collar and cravat, and well-tailored coat.

Davy Crockett – who rather preferred to be known as David Crockett, as a gentleman, rather than as a simple, blunt-spoken frontiersman — was in his lifetime the most famous of the three, and also a latecomer to Texas. A politician and a personality, he was a restless spirit, never quite entirely content with where he was, or what he was doing for long. One senses that he would have been the most congenial of the three: relatively soft-spoken, adept with words – a skilled politician. He played the fiddle, and probably did not wear a coonskin cap or a fringed leather jacket; he looks quite the polished, genteel and well-dressed gentleman in the best-known portrait of him, in high collar and cravat, and well-tailored coat.

And so by different paths, they came to the Alamo, a sprawling and tumbledown mission compound, much too large to be defended by the relative handful of men and artillery pieces they had with them. They stayed to defend it, for reasons that they perhaps didn’t articulate very well to themselves, save for in Travis’s immortal letters. Bowie was deathly ill as the siege began, Crockett was new-come to the country, in search of adventure more than glory. None of them perfect heroes by any standard, then or now… but of such rough clay are legends made.

Recent Comments