No, not that sort of brush – not a narrow escape from a driver on a cellphone running a red light, or a particularly embittered book critic – but a walk through an old cemetery near Fredericksburg, Texas. About a year ago, I had a two-day event: a presentation at dinner for museum volunteers at the Pioneer Museum in Fredericksburg, and the next day, a book-signing at the local independent bookstore. Clara Jung, who Blondie and I met at the dinner, asked if we would like to see the old Catholic Pioneer cemetery, if we had time the next day. And of course – after she told us a little bit about it, we said yes. It’s not the main Catholic cemetery; which is all very tidy and orderly and well-organized, or the main city burial ground, which is just over Town Creek, and a couple of blocks in back of the Nimitz Museum, once the grandest, most hospitable and best-run hotel between Austin and El Paso, in the days before the transcontinental railway, when the fastest way to travel comfortably involved a coach and horse teams.

No, not that sort of brush – not a narrow escape from a driver on a cellphone running a red light, or a particularly embittered book critic – but a walk through an old cemetery near Fredericksburg, Texas. About a year ago, I had a two-day event: a presentation at dinner for museum volunteers at the Pioneer Museum in Fredericksburg, and the next day, a book-signing at the local independent bookstore. Clara Jung, who Blondie and I met at the dinner, asked if we would like to see the old Catholic Pioneer cemetery, if we had time the next day. And of course – after she told us a little bit about it, we said yes. It’s not the main Catholic cemetery; which is all very tidy and orderly and well-organized, or the main city burial ground, which is just over Town Creek, and a couple of blocks in back of the Nimitz Museum, once the grandest, most hospitable and best-run hotel between Austin and El Paso, in the days before the transcontinental railway, when the fastest way to travel comfortably involved a coach and horse teams.

And the fact that there should be a little, quarter-acre sized cemetery tucked away in the middle of scrub oak and cedar brush is not all that unusual. Odd as it seems, all over Texas there are small graveyards tucked away in all kinds of odd corners not directly associated with a church. Many of them are remnants of small town’s burial grounds – there is one halfway up Perrin Beital, right smack dab in the middle of the gas stations, auto parts stores, budget hotels and pawn shops. There is another just off Stahl Road, not three or four blocks from where I live, with tract houses all around, and a tiny enclosure on Evans Road, in under the shade of some oak trees near an old farmhouse. In the old days, far from towns and churches, sometimes people just wanted to have their kin buried close by – so many of the old ranches and farmsteads had a family burial ground.

And the fact that there should be a little, quarter-acre sized cemetery tucked away in the middle of scrub oak and cedar brush is not all that unusual. Odd as it seems, all over Texas there are small graveyards tucked away in all kinds of odd corners not directly associated with a church. Many of them are remnants of small town’s burial grounds – there is one halfway up Perrin Beital, right smack dab in the middle of the gas stations, auto parts stores, budget hotels and pawn shops. There is another just off Stahl Road, not three or four blocks from where I live, with tract houses all around, and a tiny enclosure on Evans Road, in under the shade of some oak trees near an old farmhouse. In the old days, far from towns and churches, sometimes people just wanted to have their kin buried close by – so many of the old ranches and farmsteads had a family burial ground.

This particular graveyard has about fifty graves in it, being used for only the short space of about fifteen years, from the late 1850s up to the early 1870s. All of the names – save two, are German. (The two exceptions are Hispanic.) Most of the remaining original and badly weathered stones are in German also. Our guide to the old graveyard lives in a nicely remodeled 1970s house a short distance away – she drives past it every day. Several of them are surrounded with rusting enclosures, but many of the graves had no more marking than a badly decayed wooden marker. A few have metal tags mounted on a metal stake driven into the ground – any stone marker being either long-gone or never installed in the first place. The descendent of one of the families buried there is doing new flat marker stones; he is getting the pinkish granite slabs at cost and doing the carving himself.

This particular graveyard has about fifty graves in it, being used for only the short space of about fifteen years, from the late 1850s up to the early 1870s. All of the names – save two, are German. (The two exceptions are Hispanic.) Most of the remaining original and badly weathered stones are in German also. Our guide to the old graveyard lives in a nicely remodeled 1970s house a short distance away – she drives past it every day. Several of them are surrounded with rusting enclosures, but many of the graves had no more marking than a badly decayed wooden marker. A few have metal tags mounted on a metal stake driven into the ground – any stone marker being either long-gone or never installed in the first place. The descendent of one of the families buried there is doing new flat marker stones; he is getting the pinkish granite slabs at cost and doing the carving himself.

But even the dates are clear on the old stones, and it is the dates that told the most tragic stories of all – as most of the graves were for babies and children. There could be no clearer reminder that life for children – pre-vaccine, pre-antibiotic, and pre-sterile standards for the doctor’s surgery – was perilous, and apt to be cut suddenly, heartbreaking short. An infected cut, a cold which brought on pneumonia, an epidemic of one of those diseases like typhoid or diphtheria – which now happen so rarely to children that modern pediatricians might not even recognize the symptoms – tainted milk or bad water; all of these could be mortal for a small child … and loving and protective parents would be helpless. Over and over again, as related on the forlorn pink granite slabs, or on the weathered limestone crosses – children died after living a few days, months – even just a few hours; dead at the age of two, or four, or five. Most heartbreaking to imagine were two pairs of stones with the same family names, and listed dates of death merely days apart, in 1861. An older sister of eight or nine, a little brother of three or so … imagine the frantic grief of a mother, nursing her sick children with home remedies, with herbal teas and sponge-baths, sitting up at night with them … and then losing one. And within another day or so, losing the other. I think there must have been some kind of epidemic in 1861 – I know there was a horrific diphtheria epidemic in the last year or so of the Civil War. I had read in a brief biography of Fredericksburg’s main doctor, that he had so many patients at that time that his wife drove his trap from house to house, from patient to patient, so that he could snatch a few moments of sleep during those moments. Someone, now that the old cemetery has been rescued from neglect and brush, adorns the children’s graves with these little porcelain angel-bells. Our guide says that the deer step on them, knock them over and they chip and break – so it’s almost an exercise in futility.

But even the dates are clear on the old stones, and it is the dates that told the most tragic stories of all – as most of the graves were for babies and children. There could be no clearer reminder that life for children – pre-vaccine, pre-antibiotic, and pre-sterile standards for the doctor’s surgery – was perilous, and apt to be cut suddenly, heartbreaking short. An infected cut, a cold which brought on pneumonia, an epidemic of one of those diseases like typhoid or diphtheria – which now happen so rarely to children that modern pediatricians might not even recognize the symptoms – tainted milk or bad water; all of these could be mortal for a small child … and loving and protective parents would be helpless. Over and over again, as related on the forlorn pink granite slabs, or on the weathered limestone crosses – children died after living a few days, months – even just a few hours; dead at the age of two, or four, or five. Most heartbreaking to imagine were two pairs of stones with the same family names, and listed dates of death merely days apart, in 1861. An older sister of eight or nine, a little brother of three or so … imagine the frantic grief of a mother, nursing her sick children with home remedies, with herbal teas and sponge-baths, sitting up at night with them … and then losing one. And within another day or so, losing the other. I think there must have been some kind of epidemic in 1861 – I know there was a horrific diphtheria epidemic in the last year or so of the Civil War. I had read in a brief biography of Fredericksburg’s main doctor, that he had so many patients at that time that his wife drove his trap from house to house, from patient to patient, so that he could snatch a few moments of sleep during those moments. Someone, now that the old cemetery has been rescued from neglect and brush, adorns the children’s graves with these little porcelain angel-bells. Our guide says that the deer step on them, knock them over and they chip and break – so it’s almost an exercise in futility.

It was a relief to come upon that handful of stones marking the last resting place of those who beat the odds and managed to live to some kind of maturity, even into ripe old age. Oh, thank God – there are some grownups here! Not many in comparison to the children – but some of them have their own sad stories:

It was a relief to come upon that handful of stones marking the last resting place of those who beat the odds and managed to live to some kind of maturity, even into ripe old age. Oh, thank God – there are some grownups here! Not many in comparison to the children – but some of them have their own sad stories:

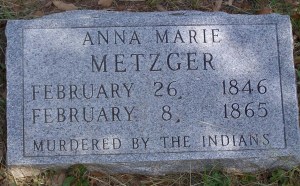

This one, I thought I recognized the surname: there was an Emma Metzger whose older sister worked at the Nimitz Hotel during the last year of the Civil War. She and her younger sister Anna went in to town one day from their parent’s farm nearby, to carry a message from their mother to the sister. On their return, they were surprised by a band of Indians, Kiowa or Comanche. Emma was killed, and Anna carried away, according to an account published here – she was taken to Indian Territory by her captors and managed to escape a year later, returning to her parents, and eventually marrying a man who settled in Mason, a man who had been in the posse who chased after the Indian raiders who had taken her and killed her sister.

This one, I thought I recognized the surname: there was an Emma Metzger whose older sister worked at the Nimitz Hotel during the last year of the Civil War. She and her younger sister Anna went in to town one day from their parent’s farm nearby, to carry a message from their mother to the sister. On their return, they were surprised by a band of Indians, Kiowa or Comanche. Emma was killed, and Anna carried away, according to an account published here – she was taken to Indian Territory by her captors and managed to escape a year later, returning to her parents, and eventually marrying a man who settled in Mason, a man who had been in the posse who chased after the Indian raiders who had taken her and killed her sister.

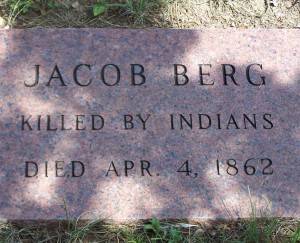

This surname I also recognized: There was a local character – an inventor and stone-mason named Peter Berg, who had come with the Adelsverein migration, along with his brother – also a stonemason. Eventually, after being jilted by a woman who had promised to marry him, Peter Berg became a sort of hermit, living in an eccentric stone tower that be built himself, back in the hills. At some point, his brother was killed by Indians, and Peter Berg turned to distilling very fine whiskey, and selling that was how he made a living. Perhaps this is where his brother was buried. Peter Berg wouldn’t have been buried in consecrated ground, though – he killed himself, ages later, turning his own shotgun on himself, as he lay on his bed. No one would have known of it, save that the shotgun blast also set fire to the bedding, and his nearest neighbor saw the puffs of smoke.

This surname I also recognized: There was a local character – an inventor and stone-mason named Peter Berg, who had come with the Adelsverein migration, along with his brother – also a stonemason. Eventually, after being jilted by a woman who had promised to marry him, Peter Berg became a sort of hermit, living in an eccentric stone tower that be built himself, back in the hills. At some point, his brother was killed by Indians, and Peter Berg turned to distilling very fine whiskey, and selling that was how he made a living. Perhaps this is where his brother was buried. Peter Berg wouldn’t have been buried in consecrated ground, though – he killed himself, ages later, turning his own shotgun on himself, as he lay on his bed. No one would have known of it, save that the shotgun blast also set fire to the bedding, and his nearest neighbor saw the puffs of smoke.

Finally – and rather reassuringly – there were the graves of a married couple, both of whom lived into old age, as it was then counted, who must have come with the first Verein settlers in those last years when Texas was still an independent republic. Born in Germany, immigrated as adults and settled on the wild frontier, lived through all the early hardships and heartbreak, the wars with Indians and the Hanging Band; surviving epidemics and accidents, childbirth and the killing labor required of anyone settling in a new land. The last and most ornate monument was for Grandmother Maria Magdalena Leyendecker, who achieved the great age of 70; born in Germany, eventually becoming the grandmother and great-grandmother of children, who saw to it that she had a suitable monument – with an epitaph in English carved onto it. In the end, she had become an American.

Finally – and rather reassuringly – there were the graves of a married couple, both of whom lived into old age, as it was then counted, who must have come with the first Verein settlers in those last years when Texas was still an independent republic. Born in Germany, immigrated as adults and settled on the wild frontier, lived through all the early hardships and heartbreak, the wars with Indians and the Hanging Band; surviving epidemics and accidents, childbirth and the killing labor required of anyone settling in a new land. The last and most ornate monument was for Grandmother Maria Magdalena Leyendecker, who achieved the great age of 70; born in Germany, eventually becoming the grandmother and great-grandmother of children, who saw to it that she had a suitable monument – with an epitaph in English carved onto it. In the end, she had become an American.

Ms. Hayes,

Thank you for writing about this original catholic cemetery in Fredericksburg. My g,g,g, grandfather is buried here (Jacob Roeder, from Berod, Germany). Jacob Roeder’s grave has a beautiful pink granite marker as well as the original limestone upright marker that is still readable. Both Jacob, and his wife Margaretha Roeder, were some of the fortunate 1845 Adelsverein pioneers to have survived the journey to Fredericksburg and lived into their late 50’s and 60’s.

Richard Roeder

Springdale, Arkansas and Albert, Texas

(p.s. I’m in the middle of reading your Adelsverein Trilogy and loving every minute of it!)

Thanks, Richard – it was an eye-opening excursion – I’ll look around, I might yet have a picture of your ggggrandfather’s grave, too!

Enjoy the Trilogy – I hardly had to make up anything at all, as what happened in fact was pretty riveting!

Thank you so much for your info about this cemetery. A family member recently moved to FBG, discovered this cemetery and showed it to me during a recent visit to the area. I found so many graves of children and began a search to see what could have caused so many to be buried there. Very interesting and most helpful.