Yes, there was a real Philip Nolan, and the writer Edward Everett Hale was apparently remorseful over borrowing his name for the main character in his famous patriotic short story, The Man Without A Country. The real Philip Nolan had a country – and an eye possibly on several others, which led to a number of wild and incredible adventures. The one of those countries was Texas, then a Spanish possession, a far provincial outpost of Mexico, then a major jewel in the crown of Spain’s overseas colonies. Like the fictional Philip Nolan – supposedly a friend of Aaron Burr and entangled in the latter’s possibly traitorous schemes, the real Philip Nolan also had a friend in high places. Like Burr, this friend was neck deep in all sorts of schemes, plots and double-deals. Unlike Burr, Nolan was also this friend’s trusted employee and agent. That highly placed and influential friend was one James Wilkinson, sometime soldier, once and again the most senior general in the Army of the infant United States – and paid agent of the Spanish crown – acidly described by a historian of the times as never having won a battle or lost a court-martial, and another as “the most consummate artist in treason that the nation ever possessed.” Wilkinson was an inveterate plotter and schemer, with a finger in all sorts of schemes, beginning as a young officer in the Revolutionary War to the time he died of old age in1821. The part about “dying of old-age” is perfectly astounding, to anyone who has read of his close association with all sorts of shady dealings. It passes the miraculous, how the infant United States managed to survive the baleful presence of Wilkinson, lurking in the corridors of power. It might thus be argued that our founding fathers were a shrewd enough lot, to have prevented a piece of work like Wilkinson from doing more damage than he did. It would have argued even more for their general perspicuity, though, if he had been unceremoniously shot at dawn, or hung by the neck by any one of the three countries which did business with Wilkenson – and whom he cheerfully would have sold out to any one of those others who had offered a higher bid.

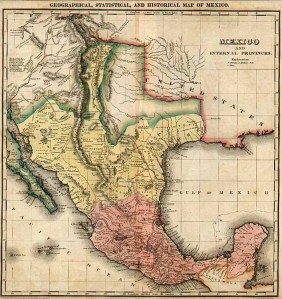

Yes, there was a real Philip Nolan, and the writer Edward Everett Hale was apparently remorseful over borrowing his name for the main character in his famous patriotic short story, The Man Without A Country. The real Philip Nolan had a country – and an eye possibly on several others, which led to a number of wild and incredible adventures. The one of those countries was Texas, then a Spanish possession, a far provincial outpost of Mexico, then a major jewel in the crown of Spain’s overseas colonies. Like the fictional Philip Nolan – supposedly a friend of Aaron Burr and entangled in the latter’s possibly traitorous schemes, the real Philip Nolan also had a friend in high places. Like Burr, this friend was neck deep in all sorts of schemes, plots and double-deals. Unlike Burr, Nolan was also this friend’s trusted employee and agent. That highly placed and influential friend was one James Wilkinson, sometime soldier, once and again the most senior general in the Army of the infant United States – and paid agent of the Spanish crown – acidly described by a historian of the times as never having won a battle or lost a court-martial, and another as “the most consummate artist in treason that the nation ever possessed.” Wilkinson was an inveterate plotter and schemer, with a finger in all sorts of schemes, beginning as a young officer in the Revolutionary War to the time he died of old age in1821. The part about “dying of old-age” is perfectly astounding, to anyone who has read of his close association with all sorts of shady dealings. It passes the miraculous, how the infant United States managed to survive the baleful presence of Wilkinson, lurking in the corridors of power. It might thus be argued that our founding fathers were a shrewd enough lot, to have prevented a piece of work like Wilkinson from doing more damage than he did. It would have argued even more for their general perspicuity, though, if he had been unceremoniously shot at dawn, or hung by the neck by any one of the three countries which did business with Wilkenson – and whom he cheerfully would have sold out to any one of those others who had offered a higher bid.

But it is Wilkinson’s particular protege who is the subject of this essay – supposedly born in Ireland, and apparently well-educated, who worked for Wilkinson as secretary, bookkeeper and apparently general all around go-to guy. He was possibly also the first American to deliberately venture far into Texas and return to tell the tale, not once but several times, at a time when an aging and sclerotic Spanish empire was looking nervously and very much askance at the bumptious and venturesome young democracy whose frontiers moved ever closer to its own. The welcome mat was most definitely not out; adventurous trespassers were either driven back – or taken to Mexico in irons and put to work in penal servitude. (Certain exceptions had been made for Catholics, or those who could make some convincing pretense of being Irish, or otherwise convince the Spanish authorities in Texas of their relative harmlessness.)

In the year 1791, Nolan procured a passport from the Spanish governor of New Orleans, and permission to venture into Texas, ostensibly in pursuit of trade; goods for horses, which were plentiful, easy to catch and profitable. Still quite young, around the age of twenty, and not quite as wily as his employer, Nolan had his trade goods confiscated in San Antonio, and was forced to flee into the back country to evade arrest. Amazingly, he lived among the Indians (of which tribe is unknown) and earned back his stake by trapping sufficient beaver pelts to buy his way out of trouble with the San Antonio authorities – and a herd of horses. Several years later, armed with another passport, Nolan ventured into Texas again, remaining in San Antonio long enough to ingratiate himself with the governor, Manuel Munoz, be included in the census, and to court a local belle. This time, he returned to Louisiana with a larger herd of horses. For a time after the second trip, Nolan worked for an American boundary commissioner, surveying and mapping the Mississippi River, which seemed to have aroused the suspicious of other Spanish authorities, including the Viceroy, the King of Spain’s good right hand in Mexico. Obviously, some of these Spanish and Mexican officials were not quite as susceptible to Nolan’s charm and the ever-slippery Wilkenson’s conniving – for he was still very much Wilkenson’s protege and possibly agent. Still – he managed to get a legitimate passport for one more trading trip into Texas. Trading was the cover story, but Nolan was also supposed to map what he saw in Texas, although no maps have ever been found. He remained in Texas for two or three years, marrying and fathering a daughter, before leaving at top speed. The Viceroy had given orders for his arrest, but protected by his friendship with Manuel Munoz, he left Spanish Texas under safe-conduct, accompanied by a herd of nearly 1,500 horses.

Suspicions of his activities being aroused, there would be no more legitimate passports to do business in Texas for Nolan. He had separated from the wife that he left behind there. In the interim before he ventured on one more expedition – an illegal one, unblessed by officials of any nation – he married a young woman from an influential French-Creole family in Natchez. Late in the year 1800 he crossed the border north of present-day Nacogdoches, with a party of thirty or forty men, ostensibly to capture more horses. What Nolan’s aim was only became clear after that point – and that was to explore and map the wildernesses of Texas with an eye towards conquest. Nolan had taken a page from one of Wilkenson’s plans for splitting off a chunk of western territory for himself.

This was more than some of Nolan’s men had bargained for. Three of them promptly deserted and hot-footed it all the way back to Natchez, where they freely talked about what Nolan was up to. Within a few months – such was the speed of communications in a time where messages could travel no faster than a horse-courier or a sailing-ship – Nolan’s expedition was common knowlege in Natchez, and to the Spanish authorities in Mexico . By then Nolan and his remaining men had pushed through the pine woods, into the central grassy plains, the haunts of buffalo herds, wild horses and the Comanche Indians. In March of 1801, they were pursued by a detachment of regular soldiers from the Presidio of Nacogdoches, pursued relentlessly and with Jauvert-like determination. Eventually, Nolan and about twenty of his party were cornered in a roofless wooden and earth entrenchment near the Blanco River. Outnumbered four to one, they fought doggedly until Nolan was killed by cannon-fire. The Spanish lieutenant in command of the Nacogdoches company graciously permitted the defeated survivors to bury him in an unmarked grave, which has never been found – after cutting off his ears. The losing survivors were sent to the mines, and the winners no doubt congratulated themselves on having seen off yet another free-booting adventurer, a filibustero, a rogue and all around land-pirate.

An ocean and half a continent away, on the same day that Philip Nolan was buried, the various treaties of San Idolfonso were being signed. These treaties would clear the way for the Louisiana Purchase. Before the first decade of the 19th century was out, more of Philip Nolan’s kind would be looking across the Sabine River and wondering if they would have better luck.

Recent Comments