It was always hoped, among the rebellious Anglo settlers in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas that a successful bid for independence from the increasingly authoritarian and centralist government of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna would be followed promptly by annexation by the United States. Certainly it was the hope of Sam Houston, almost from the beginning and possibly even earlier – just as much as it was the worst fear of Santa Anna’s on-again off-again administration. Flushed with a victory snatched from between the teeth of defeat at San Jacinto, and crowned with the capture of Santa Anna himself, the Texians anticipated joining the United States.

It was always hoped, among the rebellious Anglo settlers in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas that a successful bid for independence from the increasingly authoritarian and centralist government of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna would be followed promptly by annexation by the United States. Certainly it was the hope of Sam Houston, almost from the beginning and possibly even earlier – just as much as it was the worst fear of Santa Anna’s on-again off-again administration. Flushed with a victory snatched from between the teeth of defeat at San Jacinto, and crowned with the capture of Santa Anna himself, the Texians anticipated joining the United States.

But it did not work out – at least not right away. First, the then-president Andrew Jackson did not dare extend immediate recognition or offer annexation to Texas, for to do so before Mexico – or anyone else – recognized Texas as an independent state would almost certainly be construed as an act of war by Mexico. The United States gladly recognized Texas as an independent nation after a decent interval, but held off annexation for eight long years. It was political, of course – the politics of abolition and slavery, the bug-bear of mid 19th century American politics. Texas had been largely settled by southerners, who had been permitted to bring their slaves. Texas, independent or not, was essentially a slave state, although there were never so many slaves in Texas as there were in other and more long-established states. Large scale agriculture in Texas – rice, sugar and cotton – was not so dependent upon the labor of large work gangs. Most households who owned slaves owned only a relative handful, and curiously, many slaves hired out and worked for wages in skilled or semi-skilled trades. But even so; they were still slaves, owned, traded and purchased as surely as any livestock.

By the 1830s the matter of chattel slavery, ‘the peculiar institution’ as it was termed – was a matter beginning to roil public thinking, as the adolescent United States spilled over the Appalachians and began filling in those rich lands east of the Mississippi, and in the upper Midwest. Slowly and gradually what had been a private, ethical choice about the use of slave labor began to have political and social ramifications. Would slavery be allowed in newly acquired territories and states? And if so – where? The rift between those who held slavery to morally insupportable, a crime against humanity, and those who held to be economically necessary and even a social benefit was just beginning to divide what had been fractiously united since the end of the Revolution – a Revolution that still green in living memory. But in 1838, the practice of slavery in Texas put a stop to Texas’ inital essay in annexation: Northern Abolitionists, led by John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts filibustered the first resolution of annexation to death, in a speech that allegedly lasted 22 days. In the bitterly-fought elections of 1844, Henry Clay of the Whigs opposed annexation mightily, Democrat James Polk came out in favor . . . but in the meantime – from that first rejection, until 1846, the Republic of Texas treaded water. Sam Houston, who favored annexation, was formally elected to the Presidency of the Republic. He and his scratch army had won the war of independence, extracted concessions and a peace treaty from General Santa Anna, and briskly settled down to conduct the business of the state in the manner which they had wished to do all along. Unfortunately, Texas was poor in everything but land, energy and hopeful ambition . . . and plagued with enemies on two fronts. Sam Houston would have to manage on a shoe-string, to fight off resentful Mexico, ever-ready to create trouble for the colony which had escaped it’s control, find allies and recognition among the Europeans . . . and either defeat or make a peace with the relentless and aggressive Comanche. His government was funded by customs duties on imported goods, license fees and land taxes. A bond issue was initiated, which would have redeemed Texas finances and paid existing debts, – unfortunately, the bonds went on the market just as the United States was enduring a depression and Houston’s term as president came to an end. He could not serve a consecutive term.

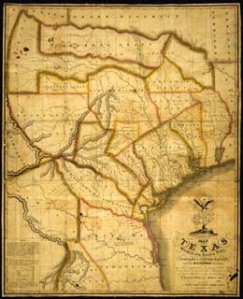

His vice-president, successor in office and eventual adversary, Mirabeau Lamar had more grandiose ambitions, apparently believing with a whole heart that Texas could and ought to be a genuinely independent nation. His goals were only exceeded by his actual lack of administrative experience. Lamar wanted to pursue foreign loans, foreign recognition, a strong defense, never mind begging for annexation, expelling the Cherokee from east Texas and settling the hash of the Comanche by any means necessary. He also set out the foundations of public education in Texas by setting aside a quantity of public land in each county to support public schools, and another quantity for the establishment of two universities. Lamar rebuilt the Army, and he established a new and hopefully permanent capitol city for Texas, at Austin on the upper Colorado River – at the center of the claimed territories, but in actuality on the edge of the frontier; excellent ambitions, all – but without any kind of solid funding, doomed to failure. Finally, an ill-planned expedition to route the profitable Santa Fe trade through Texas succeeded only in reigniting a running cold war with Mexico.

All of these disasters put an end to Lamar’s plans, and left Texas with more than $600 million in public debt. Sam Houston, elected again as president of the republic, kept his cards as close to his vest as he ever had done in the long brutal retreat of the Runaway Scrape. This was the time of Mexican incursions into the lowlands around Goliad, Victoria and San Antonio under Vazquez and Woll, the ill-fated Mier Expedition . . . and while sometimes it seemed that Houston was being damned on one side for not making effective peace with Mexico, and on the other for not making vigorous war. But Houston was playing a deeper game, during the final years of his second term; he was having another go at annexation, only this time going at it indirectly. The British had recognized Texas as an independent nation in mid-1842. British diplomats were attempting to mediate between Mexico and Texas (this was following upon military incursions into Texas by the Mexican Army) and British mercantile interests were most ready, willing and able to support trade relations with the Texas market: manufactured goods for cotton. Houston instructed his minister in Washington to reject any approaches regarding annexation, as it might upset those new relationships with the British; to talk up those relationships extensively, and in fact, to raise the possibly that Texas might become a British protectorate. What he was doing, as he explained in a letter to a close confidant, was like a young woman exciting the interest and possessive jealousy of the man she really wanted, by flirting openly with another. This put a whole new complexion on the annexation matter, as far as the United States was concerned – no doubt aided by the fact that the clear winner of the 1844 presidential elections was Democrat James Polk. Polk’s campaign platform had included annexation of Texas, and sitting President John Tyler – who had been a quiet supporter of that cause as well, decided to recommend that Congress annex Texas by joint resolution.

The resolution offered everything that Houston had wanted – and was accepted by special convention of the Texas Congress. The formal ceremony took place on February 19th, 1846, in the muddy little city of Austin on the Colorado: Houston had already been replaced as President by Dr. Anson Jones. In front of a large crowd gathered, Jones turned over political authority to the newly-elected governor, and shook out the ropes on the flagstaff to lower the flag of the Republic for the last time – and to raise the Stars and Stripes of the United States. “The final act in this great drama is now performed – the Republic of Texas is no more.” When the Lone Star flag came down, Sam Houston was the one who stepped forward to gather it up in his arms. It was an unexpectedly moving moment for the audience; it had been a long decade since San Jacinto, interesting in the sense of the old Chinese curse; no doubt many of them were as nostalgic as they were relieved to have those exciting times at an end. But history does not end. Sam Houston would have his heart broken fifteen years later, when Texas secceded from the Union on the eve of the Civil War.

General and President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna had never ceased to resent how one-half of the province of Coahuila-y-Tejas had been wrenched from the grasp of Mexico by the efforts of a scratch army of volunteer and barely trained rebel upstarts who had the nerve to think they could govern themselves, thank you. For the decade-long life of the Republic, war on the border with Mexico continued at a slow simmer, now and again flaring up into open conflict: a punitive expedition here, a retaliatory strike there, fears of subversion, and of encouraging raids by bandits and Indians, finally resulting in an all-out war between the United States and Mexico when Texas chose to be annexed by the United States. So when General Adrian Woll, a French soldier of fortune who was one of Lopez de Santa Anna’s most trusted commanders brought an expeditionary force all the from the Rio Grande and swooped down on the relatively unprotected town . . . this was an action not entirely unexpected. However, the speed, the secrecy of his maneuvers, and the overwhelming force that Woll brought with him and the depth that he penetrated intoTexas– all that did manage to catch the town by surprise. Woll and his well-equipped, well-armored and well supplied cavalry occupied the town after token resistance by those Anglo citizens who were in town for a meeting of the district court. So, score one for General Woll as an able soldier and leader.

General and President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna had never ceased to resent how one-half of the province of Coahuila-y-Tejas had been wrenched from the grasp of Mexico by the efforts of a scratch army of volunteer and barely trained rebel upstarts who had the nerve to think they could govern themselves, thank you. For the decade-long life of the Republic, war on the border with Mexico continued at a slow simmer, now and again flaring up into open conflict: a punitive expedition here, a retaliatory strike there, fears of subversion, and of encouraging raids by bandits and Indians, finally resulting in an all-out war between the United States and Mexico when Texas chose to be annexed by the United States. So when General Adrian Woll, a French soldier of fortune who was one of Lopez de Santa Anna’s most trusted commanders brought an expeditionary force all the from the Rio Grande and swooped down on the relatively unprotected town . . . this was an action not entirely unexpected. However, the speed, the secrecy of his maneuvers, and the overwhelming force that Woll brought with him and the depth that he penetrated intoTexas– all that did manage to catch the town by surprise. Woll and his well-equipped, well-armored and well supplied cavalry occupied the town after token resistance by those Anglo citizens who were in town for a meeting of the district court. So, score one for General Woll as an able soldier and leader.

Recent Comments