(All right, then – I have been working away on one of the works in progress – a continuation of the family saga established in the Adelsverein Trilogy, and suggested in the Daughter of Texas/Deep in the Heart prelude. What happens when the granddaughter of Race Vining’s wife in Boston comes west … and marries peripatetic adventurer and long-time bachelor Fredi Steinmetz?)

Chapter 20 – A Man of Family

“Sophie, my dear,” said Lottie Thurmond on the occasion of the baptism of the Steinmetz’ sixth child and third son, “When I suggested after your wedding – and it was only a suggestion, mind you, although based on Scriptural authority – that you and Fred should go fourth and multiply, I did not for a moment think that you should take me so literally. It’s as if you are attempting to fill the children’s Sunday school single-handed.”

“We love children,” Sophia replied, serenely. She settled baby Christian to a more comfortable position in her lap. “And we agreed that we would try and have a large family.”

“Yes, but it must seem as if every time Fred throws his trousers on the foot of the bed, you are in the family way again. Six children in ten years! At this rate, you will never get your figure entirely back.”

“I don’t care,” Sophia smiled at her friend. They were sitting in the parlor of Lottie’s house. “Looking after the children and the house keeps me thin, and I never was very plump to begin with.”

“At least, motherhood suits you,” Lottie acknowledged in humorous resignation. “And you are happy in it. And fatherhood suits Fred – who would have ever thought it!”

Out in the garden, Fred was throwing horses-shoes with the older children, while Frank Thurmond smoked a cigar in the shade of the one cottonwood tree in the Thurmond’s garden. Lottie despaired of ever having grass grow in it, and had settled on raked gravel and pots of shrubs and flowers. Now the children romped with happy energy, little constrained by their good Sunday clothes, for Sophia had long decided to be practical. Minnie, Carlotta and Annabelle all wore sailor dresses of stout broadcloth, in the same general cut, and handed down from sister to sister, as they grew. Their brothers Charles Henry and Fred Harvey would likely follow the same pattern as far as hand-me-down clothing went. They were stair-step children, from Minnie down to the toddler Fred, although Annabelle and Charles Henry were twins, and otherwise identical. This had pleased Fred Steinmetz very much. He reminded Sophia that he was a twin himself, and there was a pair of twins in his sister’s family as well. Sophia loved them all with fierce affection, although if pressed, she would have to confess that she was especially fond of Minnie, grave and intelligent beyond her nine years. It seemed that she had inherited Great Aunt Minnie’s intellectual leanings along with the name.

“So, this journey to Galveston is still in your plans?” Lottie asked.

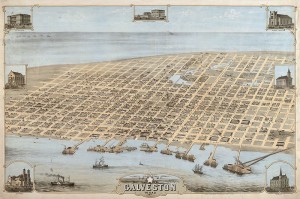

“Oh, yes. It’s going to be quite an occasion for all of Fred’s relations – the wedding of his oldest nephew’s daughter. And it will be the first time that I will be meeting most of them. His sister and her son and daughter-in-law came out to Deming four years ago, so I have met them – her son was the one who painted those perfectly splendid pictures which you admired so much in our parlor. My friend Laura, whom I shared a room with the first year that I worked for the Harvey House? She lives there now. In her letters, she says such wonderful things – so very modern and fine! The seashore there is marvelous, and it is almost the richest town in Texas … and I am actually looking forward to it. It’s been … it seems like forever since I saw an ocean.”

“You still don’t sound as if you are looking forward to it,” Lottie observed, acutely, and Sophia sighed. “Is it the thought of a long train journey?”

“No – I still adore traveling by train, and I have friends in so many places! The children will love the excursion, I am certain …”

“Fred’s family, then?”

“No, although it will be quite daunting for us; Fred married me so very late … all his sisters and his brothers’ children are quite grown, so much older than our little gaggle. I imagine that I will be the object of considerable curiosity… but his sister is quite the queenly matriarch, and she approves of me, at any rate. No, it’s my nephew, Richie. He’s going to come to Galveston too … with the intention of seeing me.”

“Oh, dear.” Lottie sat back in her chair, entirely sympathetic. “So that is it … this will be the son of your brother? He went to a great deal of trouble to locate you, and assure himself that you were still alive, my dear Sophie. Do you have reason to fear his interest, in some way?”

“I don’t know,” Sophia answered, bleak and miserable. She was glad that Fred and the other children were all outside. “He was a pleasant and very charming boy, and his letters to me are affectionate and what one would expect … but he was only the age of Minnie when I last saw him. My brother also appeared to everyone to be a pleasant and charming boy … but he was a monster. Once that one has been fooled in so significant a manner, one will always have doubts about one’s judgement of character, you see. And it is not just me, but our children. He is a grown man himself, now – and I fear that he will have turned out like his father.”

“Fred will be there,” Lottie spoke with stout assurance. “And all of his family; he certainly will not permit anyone to do harm to you – or the little ones, either.”

“I suppose,” Sophia acknowledged, for that was a comfortable consideration. “Fifteen years – nearly sixteen – is a long time, time in which I have put aside so much of the girl that I used to be. I hate any reminder now, of how persecuted and desperate I was. Lottie – my best friends and dearest kin – they turned their backs on me, and I was helpless! I had nowhere to go, no means of throwing back the calumnies that they heaped upon me!” Distressed and agitated, she wrung her hands together – this was the first time that she had been able to speak of her fears freely, to an understanding person. “I do not like being reminded of that person that I once was, Lottie … I fear that I might be thrown back into that helpless state of mind…”

“But you are not that helpless girl any more,” Lottie reached out her hands and captured Sophia’s in hers. “You became a strong and independent woman, with a darling family and friends who would not consider turning their back on you in distress. We become many people in our lives, as we pass through the stages of womanhood. I am no longer the sweet obedient belle that my mother sent out to snag a rich husband and you are no longer that desperate girl, escaping your brother’s machinations. Nothing in our lives can no put us back to what we were, once … not after so long a time has passed.”

“I suppose so,” Sophia confessed, somewhat comforted by Lottie’s vehemence. “And I will do my best to recall your words.”

“Do, my dear. When are you leaving for Galveston?”

“A week from tomorrow; we’ll go as far as San Antonio on the regular Pullman coach. The family has a most splendid parlor car of their own, and we’ll go on to Galveston together with those relations who live there.”

“It sounds as if it will be a wonderful excursion,” Lottie assured her. “You must write me of every detail.”

* * *

San Antonio

August 21, 1900

My dear Lottie:

Here we are safely arrived in San Antonio after our rather tiring journey. The dear children and I are all well, as is darling F. He sends his best wishes, and says that you and Frank would likely not recognize your old haunts! The old city is much changed – as have many cities – most especially by the arrival of the railroad. Little remains of the old Spanish citadel save the original chapel, now that the Army has established their new post in the hills to the north of town. The children have enjoyed the journey so far, and have been most angelic in their behavior, and Min has asked me the most searching questions – such a solemn little Miss!

Here we have met with the closer portion of F.’s family; his older sister Magda Becker, her two sons and two daughters, all with their wives and children. There is a certain consistency in appearance, by which we discern that branch of the family – a tendency to be tall, with very fair straight hair and blue eyes. The family of F.’s other sister, the Richters, (both she and her husband are deceased, alas) are also uniformly recognizable by appearance: rather shorter, with very dark hair and eyes of a brown hue. This is all complicated somewhat by intermarriage. To my astonishment, there is also a portion of the family with the surname of Vining – the very name of my maternal grandfather – and I was first assumed on the basis of my own appearance to be a connection of theirs.

On the morrow, we depart in a large party for Galveston …

* * *

Sophia omitted from her letter to Lottie one or two of the most awkward moments; once when she overheard Magda Becker’s younger daughter Charlotte Bertrand remark in astonishment to her sister-in-law,

“She is so young! Where on earth did Onkel Fredi meet up with her – I sincerely hope it was not some low dance-hall!”

Jane, the sister-in-law was the wife of Sam Becker the painter; they had stayed in Deming for several weeks, so that Sam could paint some lovely landscapes in New Mexico. Jane now replied,

“No, dear – she was working at a Harvey house. Her family was most respectable, but they fell on hard times.”

“Oh, I see.” Sophia was about to tiptoe away quietly from the doorway out to the terrace of the Richter mansion, before her presence was noted, but for Charlotte Bertrand observing,

“It is curious, though … she resembles Cousin Horrie in almost every particular. They could be brother and sister, almost. Have you noticed?”

“I can’t say that I have,” Jane replied. Shaken, Sophia slipped away. Was there some closer connection to these Texas Vinings?

The question weighed on her, especially when the Vinings – connected by marriage to both families – arrived from Austin within days; Peter Vining, the patriarch of that branch with his wife Anna – whom Sophia recalled with particular fondness from that brief meeting in Newton, at the start of her time in Fred Harvey company. Peter Vining also brought his daughter Rose and his nephew, that Horrie Vining which she was herself said to resemble. As Horrie and his wife were little older than Sophia herself, their children were of an age to be playmates with Fred and Sophia’s children.

Sophia had to admit, the likeness between herself and Horrie was more than a little unsettling; of the same light frame physically, but cast in a masculine mold, the same shape to their faces, eyes of the same blue-grey color … and the same tightly-curling light brown hair. Horrie Vining was the very image of young Grandfather Vining, in that antique portrait of he and Great-Aunt Minnie, which once had hung in the old Vining mansion on Beacon Hill.

Recent Comments