Not the whole summer, and not at a classic old-fashioned summer camp, beloved in stories of juvenile derring-do among the pines – some never-neverland in the mountains of the old north-east states, with a lake and a rivalry with the boy’s camp across the lake, a summer of crafts and campfires, spent among upper middle class peers enjoying a break from the sweltering city. No – as a teen, I had a whole week every summer at live-away camp in the upper reaches of Oak Glen; a facility owned and run by the Lutheran Church, among the apple orchards and rocky hills above Yucaipa, in San Bernardino County, up against the tall mountain range that runs along the backbone of California. I suppose that in the off-season, Camp Yolijwa served as a center for retreats and conferences among the Lutheran devout – but in the summer months, it was the camp experience for tweens and teens. I rather think the sessions were age-segregated – young teens, mid-teens, older teens, and some special sessions for … well, I’ll get to that in another post, perhaps.

Camp week began on a Sunday afternoon, after a long drive in the old Plymouth station wagon, with a week’s worth of clothes, a sleeping bag and pillow (and for me, a stack of books) packed in an old military surplus duffle bag thrown in the back, behind the passenger seat. The session ended the following Saturday mid-morning – but for me, that week was pure bliss. I looked forward to that precious week, all through the intervening year. The facilities then were relatively basic – three stepped conblock double dormitories set into the sloping hillside below the administration building, which also housed a classroom. Each dormitory consisted then of a long room fitted out with old military surplus metal bunk beds – fifteen or so, if memory serves, and a latrine and bathroom facility at the inner end. The windows at the uphill side were narrow and looked out upon nothing in particular save the lower walls of the dorm on the level above. Ten or eleven bunks were lined up with their heads against the uphill wall – but the rest were ranged along the wall with windows that looked out on the downhill side – a long meadow culminating in a grove of trees that sheltered the Lodge, and beyond that, a V of mountains that ended in a band of smog that denoted the lowlands … the little burg of Oak Glen, with Yucaipa, San Bernadino and the bigger city on the lowlands beyond. At sunset, that band turned fiery red. After the first year at Camp Yulijwa, I always took care to claim one of the upper bunks that looked out on that view. Above the mundane world, apart from it for the space of a week, removed from school and every particle of social misery, to which I was heir to, as a plump and brainy child with braces and glasses and a lack of social confidence. At Yolijwa, I could be someone else for a week; a blank slate, as it were, and among strangers. You could make yourself into something else, at camp. And I did and relished the hell out of the experience.

Oh, Camp Yolijwa, how I did love thee! The Spartan barracks of the dorms, the clear mountain air, the apple trees, the freedom to be a new person, the ephemeral comradeship of a handful of fellow campers! It was a church-based camp, of course – but I really cannot recall being particularly oppressed by this. Lutherans are generally open-minded, sometimes a bit too open-minded of late. After breakfast in the Lodge, we had brief morning devotions, when we were set free to go read the morning lesson, perhaps a bit of the Bible and meditate up them privately, wherever the spirit took us. I was in the habit of climbing into the crotch of a small tree somewhere on the grounds – this, from my habit at home, when Mom was prone to order me to do some chore or other, if she saw me reading a book in the living room. One beautiful misty morning, I saw a doe deer and her pair of spotted fauns, meandering through the trees, when I looked up from my readings. After morning vespers and meditations, we usually had some kind of religious classes; it’s in my mind that such counted for most of us against Confirmation requirements. Sometimes we went on a hike down in the canyon, to a trickle of waterfall coming down the rock face, or a field trip to a local art museum. Those classes were held in the Lodge, or sometimes in the little arena built into the slope of the hill, a stepped half-circle of simple benches. Sometime in the morning, we also had an inspection of our quarters – our dorm and bathroom were expected to be relatively spotless, swept clean, our bedding straightened, and all personal possessions put away, or at least neatly arranged.

The Lodge was a mid-century-modern construction, a vaulted ceiling, a huge stone fireplace and window-walls that looked out on the grounds, three-quarters of the way around. Half was a general meeting place, and half was the dining room, set about with the same long tables and metal folding chairs which featured in about every mid-century Lutheran parish hall ever. I don’t think that I ever ventured into the kitchen itself, which was presided over by Bert. She and her husband, Doc, were the then-permanent caretakers and whole-time staff. They lived on the grounds full-time. I don’t know if they had a small cottage somewhere, or if there was some cozy apartment attached to the Lodge. I did hear that they had a dog who had chased a bear out of the apple grove, one harsh winter. Doc and Bert were ageless – middle-aged, I recall. I don’t remember anything about Doc, particularly, but Bert was an absolutely priceless cook. The meals that emerged from the kitchen at Camp Yolijwa were amazing – the best mass-meals that I ever ate, save until the kitchen at Sondrestrom AB, Greenland. The dessert that I do remember clearly was a whole baked apple in a tender crust, with a spoonful of custard poured over. My first year there, my twenty-something aged camp-counselor was copying over Bert’s cookbook for her own use, having to reduce the quantities given for each recipe by about 90 percent. (We campers were amazingly tender of our counselor, since it had been given to us that she was married to a Marine, currently stationed at Khe Sanh. We all knew about Vietnam. We were afraid that her husband was doomed and treated her as a new or near to new-made widow.)

After lunch – recreation time. The pool was opened, and that was where just about everyone gravitated, for summertime in Southern California was hot, and the Olympic-sized pool was gloriously cool. On Thursday evenings – that was something special. We walked down some side roads, past a farmhouse in an apple grove, and climbed the fire road that wound higher and higher up the side of Pisgah Peak. We would pause for evening vespers halfway up the trail, where there was a carve-out in the mountainside, then continue up to the cleared area at the very top. It would be sunset by then – and we would spread out our sleeping bags and sleep under the stars – about as well as one could sleep on hard ground, but we were kids, and it was an adventure to sleep under the open sky on the top of a small mountain. In the morning, we would stagger down the fire road, and have breakfast in the lodge.

Oh, summer camp, the happy culmination of my year, from the seventh grade on – and then I came back several years as a camp counselor myself. I lived for that blissful week, and nothing could ever ruin it for me, not even the summer when a fellow camper tried to play the same mind games of exclusion and mean-girl scorn that I had already encountered in junior high. And I just wasn’t going to play, falling into the trap of uncertainty and self-loathing – not when I had lived for this one precious week. There was no way that this girl could ruin the week for me, so I ignored her, resolutely for the entire week – and had a marvelous time in consequence. Who was she, that someone that I neither liked or respected, could have the power to ruin my day, or my week? I had all the power! (We did sort of come to a rapprochement at the very end of camp week, when we were the last two campers waiting at the admin building for our parents to show up.) I went back to school that autumn, feeling as if I had just gotten fitted for a suit of plate armor. Nothing the middle-school mean girls could do or say could have any effect on me, after that. They had no power – or more precisely, the power that they had was only what I had allowed them. And once I stopped caring about the actions and opinions of people that I neither liked or respected … well, I had plate armor, then. After that, school was a place that I just had to be for certain hours of the day. The people in it … eh, I could take them or leave them alone, and leave them alone mostly, was what I did for all the rest of the time I spent in public school.

Camp Yolijwa is still there, in Oak Glen, California, although now it seems to be called Luther Glen. It looks now to be much expanded, with a big new main lodge where the apple orchard used to be. The old lodge at the bottom of the hill, the swimming pool and the three plain dorm buildings appear to be where I recalled them to be, but there is a road cut through the wilderness area down below the main camp precinct, where we played ‘Capture the Flag.’ My younger brother, JP, did camp there, in canvas tents on timber floors, but he was never as fond of or as loyal to Camp Yolijwa as I was.

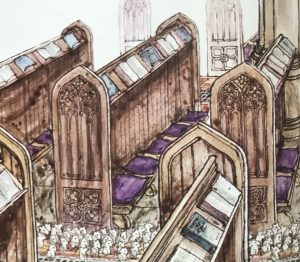

(I thought that I might have some pictures to go with this post … but none that I can find, other than some blurry black and white shots of the Lodge and cabin interiors from an old album. Maybe I can find some others, later.)

Recent Comments