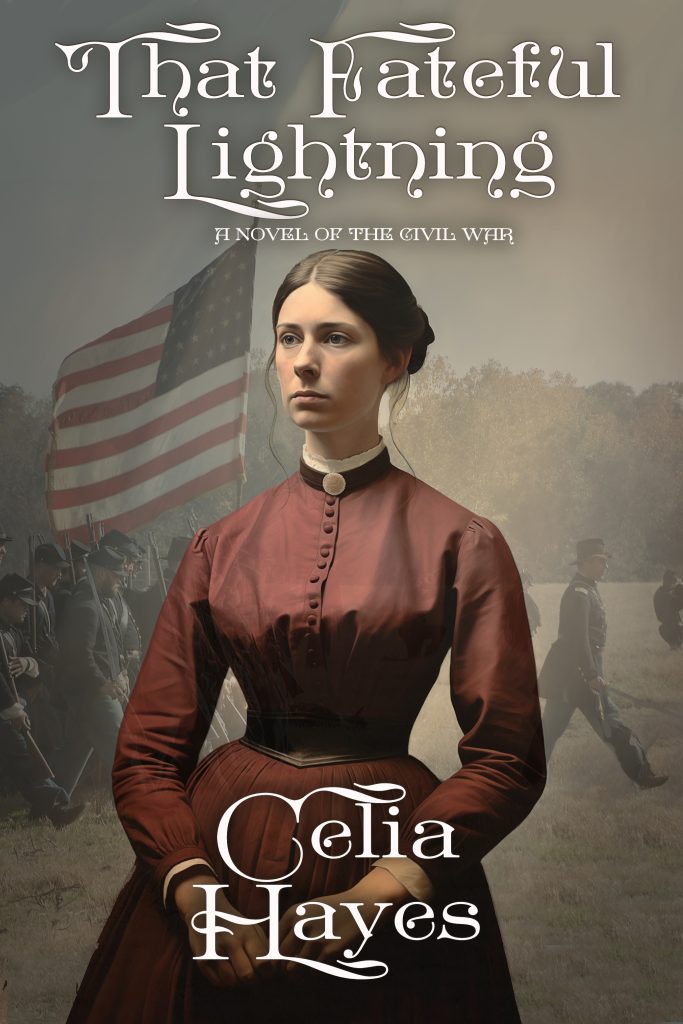

Tag-dah! The cover for That Fateful Lightning has been generated by a writer friend who dabbles in this kind of thing – Thanks to Covers Girl, for this creation, which uses a generated image of a woman, and one of my own photographs as a background! Look for this to be released in ebook and printby the end of November, 2023!

Yes, the work in progress is humming along – I hope to have it all done and ready by late November, and launch officially at Miss Ruby’s Author Corral at Giddings, the first Saturday in December. In this excerpt, Minnie Vining and Mrs. Mary Bickerdyke have a good look at the Army hospital at Cairo, Illinois, in the first summer of the War Between the States.

At the same instant that Colonel Ennis bid them good evening, and took his departure, a very young woman in a calico dress which drooped hoop-less and looked by the hem of it to have been dragged through mud and other unclean matter, emerged from the nearest tent. Her apron was also similarly stained. She carried a bucket, which she set down as soon as she saw the other two women.

“Oh, merciful heavens, Mrs. Bickerdyke – you are here!” She was a very pretty, slender young woman, worn down to a thread and very near tears. “There is so much… and so many! I have done all that I can, and the contraband women and some ladies from Cairo are helping me, but there is only so much we can do with what little the Army can spare!”

“We are here now, Miss Vining and I,” Mary Bickerdyke enfolded the younger woman in a comforting embrace. “And four boxcar-loads of supplies – linens, food, spare cots and blankets and much else as well – which are on their way this very minute from the railyard. Colonel Ennis was good enough to put a trusty sergeant and a work party at our disposal. I do not wish to waste any time; show me the hospital, so that we may make plans to remedy the dire situation as soon as we are able. We may not be able to make improvements tonight,” Mary Bickerdyke added, with particularly resolute determination, “But at least, we will have a notion of what needs to be done.”

“Everything,” Miss Safford sniffed, and rubbed her eyes. “Everything … the poor souls lie in their own filthy bedding for hours, for lack of anything clean… It is all that I can do to bring them beef tea and a concoction of willow bark, steeped in hot water, or Peruvian bark for those poor souls with the ague and chills.”

“I have sufficient funds to hire laundresses,” Mary Bickerdyke replied. “And indeed – I do suppose that the contrabands in the camp that we passed would be happy enough to be hired for that task. Now show me the hospital.”

“All right,” Miss Safford gulped back her tears with a commendable effort. “This way … the convalescents are here, those who are still ill and not cleared by Surgeon-Major Frost to return to duty with their company. They help as much as they can, but they are hardly well themselves…”

The first tent was not so awful; filled with cots and bedrolls, most occupied by men, most in a state of dishevelment, or indeed, undress. At least half of them immediately dived for the cover of blankets or those garments they had set aside in the interests of comfort within the sweltering canvas roof, as the three women entered the tent.

“They are … unclothed!” Minnie hissed in a startled undertone. It was not that she had been completely unaccustomed to the sight of naked or near-naked males – after all, when she was a girl, her brothers and their friends would swim in the Charles, when the summer heat was particularly oppressive.

“They are,” Miss Safford acknowledged, in a welter of embarrassment and fanned her flushed face with her hand. “They are still recovering, and the heat is so pernicious. I … try to think of them in the same manner as creatures in the barnyard.”

“I was married to my husband Mr. Bickerdyke for twenty years, and have two sons,” Mrs. Bickerdyke replied, serenely. “I’m not seeing a particle of anything that I didn’t already know about.”

Minnie felt the same flush of embarrassment rising in her face. Well, she would have to get used to this. It was one thing to minister to her brothers when they were ill, and when they were dying – it would be another matter entirely to see to the needs of strange men; boys, really. Perhaps she would do her best to think of them as infants and small boys, in need of sisterly or motherly care. Miss Safford, so very young and unmarried, seemed to have found a means of coping by thinking of their patients as horses and cows.

Conditions in the other tents were … abominable. Hot, filled with the stench of vomit and feces, of unclean bodies and pungent male perspiration, stale air, and the indefinable odor of sickness. Minnie tried to hold her breath as much as possible. Mary Bickerdyke’s expression remained stern and resolute, even as Miss Safford’s expression reflected a degree of shamed embarrassment. But Mary Bickerdyke was unmoved, even serene.

“Rest easy, dear boys,” she said several times, as she leaned over a cot or a bedroll, smoothing the ragged, stained covering over the shivering form underneath. “Rest easy, for in the morning, we will fix things. You will be cared for as tenderly as if you were home with your dear mother. Rest easy, boys.”

It was fully evening when their tour of the hospital tents ended. The sun had gone down in the west, well below the edge of the levee, but the sky still retained the color of a bleached sea-shell in it, edged with pale apricot shreds of cloud. The distant sounds of drill and stamping feet echoed from the distant parade ground – a sound which had become so very familiar to Minnie, as familiar as the regular ticking of the old clock in Papa-the-Judge’s study, far away in Boston. Minnie took a deep breath of relatively fresher air. The compound of tents stretched away before the three women, many lit within by oil lamps, which gave the effect of a collection of Chinese paper lanterns. A scattering of campfires sent golden sparks up into the evening air, as ephemeral as golden fireflies. A bugle on the far side of camp sent a melancholy thread of music into the air. Minnie shivered a little, half in dread, half in anticipation – this would be her life for the foreseeable future, the regular tramp of marching feet, harsh male voices, the discordant music of drum and bugle.

In the open quadrant by the hospital tents a pile of crates and trunks steadily grew, as they were unloaded from Army wagons, under the profane direction of Sgt. Sullivan – at least, profane until he noted the presence of the three women.

“God save the mark, Ma’am.” He came to them, after bawling his last set of orders and commands over his shoulder to the half-dozen soldiers laboring to unload the last wagon. “Here we have all of your traps and treasure brought from the railway … was there anything more that you wish us to do?”

“There is,” Mary Bickerdyke studied the stack of barrels and scrap-wood crates, piled next to the nearest cook tent. “Those hogshead barrels … I would like eight or ten of the soundest and least damaged to be sawn in half, and the bungs stopped with plugs. Can you do that for me by tomorrow.”

“Of course, ma’am,” Sgt. Sullivan appeared to be mildly nonplussed. After a short hesitation, he ventured a question. “May I ask, ma’am – for what purpose?”

Mary Bickerdyke looked up at him as if this were the most obvious thing in the world, although even Minnie and Miss Safford were puzzled. “For bathing the sick, of course. Those barrels will make admirable tubs. Cleanliness is essential for these poor lads – and they are filthy-dirty. We’ll start on the morrow, ladies,” she added, with a look over her shoulder at the other two women. “Miss Safford, dear – have we a place to lay our heads down tonight, and perhaps have a bite of supper? Miss Vining and I are fatigued after a long day’s journey, and tomorrow will be very busy for all of us.”

“Oh, but of course,” Miss Safford replied, somewhat relieved that the tour of the dreadful ward tents was completed. “Colonel Prentiss very kindly allotted me a tent to myself and Free Mary … she is one of the contrabands who has been assisting me … we have been issued some camp cots, and Free Mary has been friends with the cook in the nearest camp kitchen. Besides, she brings me some good cornbread that her mother bakes … she and her sister and mother all escaped together and took refuge with the Army. Free Mary will have brought us all something to eat, I am certain.”

“Good,” Minnie replied, mildly relieved that she and Mary did have a place to sleep that night – as well as the prospect of a meal, although whether it would be edible or not was a matter of conjecture. She had a packet of food in the valise which she had brought with her from Galesburg; some slabs of bread and cheese, hardboiled eggs, and some cold fried chicken, in the event of the Army cook not being anywhere near as gifted as Mrs. Norris. She was as exhausted as she had ever been, after a long train journey, and contemplating the prospect of sorting out the hospital and it’s suffering patients on the morrow. She was so tired that she thought she could have lain down and slept soundly on a bare pallet, just as the soldiers did.

With a feeling of intense anticipation and relief, Minnie packed her small traveling trunk, left instructions to Mrs. Norris and her daughters to close up the main part of the Beacon Street mansion, bid Sophie and Richie a fond, but abstracted goodbye. and set off for Chicago and the west. At last, amid the tumult of events, she had a purpose and a goal, once more, would be of use in the grand crusade against the cruelty and evil that informed the slave system. The journey was no more or less comfortable than so many others she had made over the last fifteen years. The discomfort of this excursion was a little alleviated by a night spent in a very comfortable little compartment in a special car set up as a sleeping coach. It was, Minnie thought to herself, very much like a miniature stateroom on one of the more luxurious steamboats, all polished wood with pretty curtains to be drawn against the twilight, and a little bed set with clean sheets and a feather comforter. The conductor on that train informed her that this sleeping car was a special one, an experiment of sorts, and if it proved popular enough, soon most railway lines would offer such cars for the convenience of those traveling long distances.

She arrived at the Galena & Chicago Union Station at mid-morning, refreshed from a good rest in the sleeping coach, and to her joy, Mary Livermore met her on the platform.

“My dear Minnie, it seems an age!” Mary embraced her as if they had been apart for years. “There is so much going on these days, I hardly have time to think … when were you last in Chicago? I think you had gave a lecture at the …. Was it three years ago, or longer?”

“Two years, only two years,” Minnie replied, returning the embrace. It was always startling to her to see Mary in her current incarnation, a stout middle-aged body, prim and earnest, afire with good works. She had been Mary Ashton Rice, back then; Minnie always thought of her as she was when first she and Annabelle met her at dame school in Boston, so many years ago. Mary was always in Minnie’s memory as the earnest schoolgirl with her hair tightly woven into plaits on either side of her round face, solemn and serious, when the light-hearted Annabelle teased her mercilessly.

“In any case, you are welcome as always,” Mary took her arm, and they walked out to the street. “And the train to Galesburg departs first thing in the morning, so of course you will spend the night with us … are you wearied, Minnie dear? Are you up to a diversion, before I take you home; you must be exhausted…”

“Not a bit of it,” Minnie replied, stoutly. “I had a good rest on the train, and nothing but time until tomorrow morning and the Galesburg train.”

“Oh, good,” Mary replied. “You see, we have a simply enormous bazaar today in Tremont House ballroom, to benefit the Sanitary Commission – so many of our good patriotic ladies have volunteered to make things, and to work in the booths, and I had such a large part in organizing it all that I simply have to make an appearance, even if Mrs. Armstrong does have all the volunteers so very well organized … I must introduce you to her, in any case. Feenie Armstrong is my good right hand, in Mr. Livermore’s congregation. Her husband, Mr. Armstrong, is in finance, and both are such strong supporters of our efforts. A lovely young couple, they have three very charming and well-mannered children. You would like her, I think.”

Minnie groaned. “All the dear sweet ladies, selling bits of embroidery and fancywork to each other, and to the patriotic souls… Mary, I volunteered to go with your friend Mrs. Bickerdyke, just to escape this kind of feminine flummery. Embroidery. Sweet little paintings on china. Berlin wool-work slippers, and fancy samplers. Tatting … did I ever tell you how much I despise tatting and other useless handiwork considered suitable for ladies?”

“No, you didn’t,” Mary patted Minnie’s hand. “Not above a hundred times, beginning when you pricked your fingers and bled on your sampler, and said some very rude words in Latin which your brothers had taught you. So very helpful that Madame Dubois didn’t understand Latin…”

“But all the girls who did, were shocked to their souls,” Mary smiled, impishly. “Ne’er mind, Minnie – we will not expect you to donate any goods for sale or expect you to mind a booth. I just want to introduce you around – this is a grand undertaking, and you should at least make yourself known to those dear ladies who will remain by their hearths and send up their prayers for you … and all our dear boys.”

“Very well, I shall do my best to be cordial,” Minnie relented, and Mary embraced her again, and took the small travel trunk from her.

“You will not regret it, Minnie dear,” she promised. “It will do your heart good to know that Chicago is all for Union. I am certain that there are more for Abolition here in Chicago than there are in our old dear Boston!”

“I’ll not argue that,” Minnie said, as Mary showed her to a hansom cab, waiting among a crowd of other conveyances in the street outside the station, the single horse in harness pawing the dirt at his feet with weary interest, as if he had hoped to find a grain or two of corn in the filth, but wasn’t really expecting such.

The Tremont House was the grandest of such in Chicago, Minnie knew – the cynosure of all eyes, especially of the wealthy. And the ballroom did not disappoint, especially not today, all hung with patriotic colors, and filled from pillar to pillar with tables and small booths ornamented with swags of bunting and fresh flowers, ribbon bows – and women, women everywhere, young, old and in between. Their pleasant voices, and the rustle of their skirts filled the room, at least as much as their energy and good cheer, as well as the undernote of rustling paper money and the clink of coins, as all manner of home-made pretty things changed hands.

“We had a remarkable turnout for this fair,” Mary remarked as they entered the ballroom. “Our dear Colonel Ellsworth was of this city, you will remember… our folk have taken his bloody murder at the hands of that vile Secessionist very hard. He and his Zouave company were much beloved, in Chicago.”

“I know,” Minnie replied – for the handsome Colonel of volunteers was much admired throughout the North and had been a firm friend to President Lincoln – indeed, Colonel Ellsworth had lain in state in the White House, his body lapped in bouquets of white lilies, or so Minnie had read in the newspapers. He had been shot by an innkeeper in Alexandria, across the Potomac from Washington – on a mission of taking down a taunting Confederate banner posted by the owner of the inn. A rash response to a taunt – but Minnie knew very well that men were like that. Was this war a schoolyard taunt grown to continental proportions? She wondered about that, now and again. The blood of a new martyr had focused all serious attention to the matter of war just this spring, electrifying the North after the Sumter surrender. It would not be over soon, or bloodlessly. First reckless words, then the surrender of Fort Sumter and the Federal garrison in Texas. No, words and threats had been exchanged in broadsides in print and speeches … but the death of Colonel Ellsworth, even more than Fort Sumter meant that there would be bloodshed, and blood in quantity. Likely every woman in the Tremont ballroom on this morning knew it in her heart, even if she might not admit it publicly.

Now a younger woman at the nearest booth looked up, catching Mary Livermore’s attention. She was pretty, still in the bloom of youth, clad in the most tasteful and subtly expensive of recent fashion; her brown hair, threaded with auburn highlights, was combed smoothly back from a widow’s peak in her forehead and tidied away under a modish small bonnet. Minnie thought the woman looked familiar – perhaps they had met before, when she herself was on the lecture circuit. One met so many others, and lamentably, only a handful of the most notable or eccentric really stood out in memory, sufficient to instantly attach a name. Three children stood at the woman’s side; the eldest a pretty miss of twelve or so with curls of a brighter auburn shade, offering a basket of small nosegays tied with silk ribbons for sale. The younger lads – presumably her brothers – solemnly collected payment for the flowers and made change.

“I see you are putting the children to good work, Feenie,” Mary Livermore remarked.

“My husband says that children are never too young to learn the meaning of work – or charity,” Feenie Armstrong replied with a fond smile, and Mary Livermore chuckled.

“So very correct Mr. Armstrong is in that! Never too young to be of good use in the world! Feenie, I would like to make you known to one of my oldest friends in the word; Miss Minnie Vining, this is Feenie – Mrs. Josephine Armstrong.”

“So very pleased to make your acquaintance, Mrs. Armstrong,” Minnie was still certain that she had met Mrs. Armstrong before. She knew her face; that distinct heart-shape and grey eyes were familiar. Not from Boston, though – not the daughter of old friends or a distant relative. And did she imagine the fleeting expression of … fear, fear and apprehension that crossed Mrs. Armstrong’s countenance.

“I have heard so very much about your work in the Cause,” the younger woman replied, with every evidence of pleasure, after that first brief and inexplicable moment of dread. “I had often wished to attend one of your lectures, but never had the opportunity – for which I am very sorry.”

“I share that regret,” Minnie replied, “But I am certain that we have met before – you seem very familiar to me. Might we have encountered each other through friends and kin in Boston? Were you at school there? Are your parents someone that I knew?”

“No,” Feenie Armstrong shook her head. “I don’t believe so. I was an orphan from the age of ten, but I was blessed with an attentive guardian, who sent me to school in Philadelphia and supported me until I married Mr. Armstrong.”

“Perhaps I recall someone who resembled your person,” Minnie replied, and at that moment glanced at Mrs. Armstrong’s daughter … and at that moment she realized, with a feeling like being struck by lightning where she had first encountered Feenie. Where she had first met Feenie Armstrong, or the woman who went by that name now; in Richmond, the nearly-white child named Josephine that she and Elizabeth Van Lew had purchased at the slave auction, so many years ago. A poor tearful child, frantic at being tossed in among the brutal slave system, rescued at the last minute, restored to freedom and the chance of happiness. It was all dreadfully clear in that one moment to Minnie. Josephine was a woman now grown, settled in a prosperous life, and a happy marriage, content with happy and well-mannered children. But she must still live in dread, knowing that an unthoughtful or vicious word about how she had been bought in a slave auction in Richmond at the age of eleven years, just because her father died in debt and her mother had an ancestor of the Negro race and born in bondage… did anyone know of this, save Minnie herself, and the kindly Van Lew family, who had seen to Feenie’s education and subsequent freedom into another life… Did Feenie Armstrong’s husband, even know of her past, although nothing of it was her fault in the least …

No, she wouldn’t say anything about what she knew of Mrs. Armstrong’s past.

It was a strained summer, those hectic months after the surrender of Fort Sumter; there was feeling in the air as if a powerful thunderstorm was building, lending the very air a sullen greenish cast, while the skies hazed with heavy grey clouds. The sounds of marching feet filled the streets, as militia companies drilled on the Common, and newly recruited volunteers assembled and marched away, clad in civilian motley, but proudly led by the banner of their company.

To Sophie’s barely concealed horror, in mid-summer of that restless, unsettling year, Richard was offered a commission as captain, for a Massachusetts regiment composed entirely of Irishmen, recruited in Boston and vicinity, a commission which he accepted with lively interest, since he had done as he said he would – volunteer in response to President Lincoln’s call after settling all his business obligations and tendering his resignation to his partners in the practice of law.

“The company will be interesting, the music delightful and the need for calm and resourceful leadership for these poor working fellows is most necessary, if we are to win this war,” he repeated, on the day when he appeared in a blue uniform, shining brass buttons marching in a double row across his chest. Minnie and Sophie had spent several days sewing fine gold fringe to a scarlet silk sash, for him to wear under his sword belt. “Oh, my … really, Aunt Minnie? I cannot imagine a more useless bit of chivalric flummery, but I thank you in any case. The fellows will expect that I make a show … it’s a bit like being an actor, I suppose. Like Edwin Booth, the Fiery Star … striding the boards and declaiming to the footlights…” Sophie burst into tears and Richard took her into his arms and kissed her soundly, several times. “My darling Sophie, do not disfigure your face with tears. I am going no farther than Cambridge and Camp Day for the nonce. We may celebrate Christmas at home, I assure you. The chaps in the regiment will not be cleared for active service until they have been thoroughly trained – and most of them are no more soldiers than I am, being laborers, farmers or ordinary working men, so I may assure you that we will be months about training them to be proper soldiers.”

This did not comfort Sophie in the least, while Minnie regarded Richard with a pang of mixed pride and dread. While the men of the Irish regiment might not be the stuff of which soldiers were made, at least, not at first – Richard himself looked every inch a handsome and heroic martial figure.Restless, and unsettled, Minnie confided her feelings to Lolly Bard, over tea in the front parlor. The summer breeze teased the light muslin curtains in the window overlooking the Common and brought to them the faint sound of marching feet – a sound which had become all too familiar for them both.

“I hardly have any interest now, in continuing my lecture tours,” Minnie lamented. “Since now the whole of the North is ablaze with zeal to preserve the Union and freedom for all those enslaved, there seems not to be any real purpose in it. I feel useless, useless – Lolly, when I have been a crusader for so many years. And now that Jerusalem has been conquered, then what is there for me to do now? Lay down my weapons and … what?”

Lolly nodded, looking as wise as one of the goddess Minerva’s owls. “Dear Mr. Bard used to say ‘What was the future for a soldier after the war is won? Or for a worker, once the track is laid and completed,’ – he was so very wise, my husband. I suppose that once a campaign is done, one should search around for another, to engage one’s sense of purpose … had I told you, dear Minnie – that I have been accepted as one of the Boston agents for the Sanitary Commission? To see to the needs and welfare of our soldiers. There are so many of them now, I am told that the Army Department is quite overwhelmed.”

“As they would be,” Minnie replied, crisply. “For our own federal Army was very small, and so many of them departed service to take up arms for their states, when those states withdrew…”

“But the reality remains,” Lolly blinked apologetically, “How are we to care for our soldiers, when they are wounded, sick or hungry. I believe that we must do our part for them, Minnie. Our sons and brothers …”

“You mean, that we organize bazaars to sell needlecrafts and similar flummery to the patriotic public!” Minnie snorted in disgust. She looked at the tea tray; the fragile China-import porcelain cups and the silver Paul Revere-fashioned service all laid out so lovingly by Mrs. Norris. This very week, Jeremiah Daley had served his notice to Minnie, saying that he was volunteering to be a soldier, although he was not young. He was patriotic to a fault, and still quite fit, through having been a man of active work. His wife, and her sister and mother had seen him away with the other volunteers, with a bag packed full of comforts.

“You are quite right, Minnie dear,” Lolly replied. “As it concerns yourself. Indeed, you have no patience with tedious details, and I confess that many of our lady acquaintances are exasperating … it is not their fault, of course – it all lies in how most of us were raised with limited expectations as to our role in life.”

“Oh, that I were born a man,” Minnie quoted, “For I would eat his heart – that is, the traitor Jeff Davis’ – in the marketplace!”

“Indeed,” Lolly’s sweet, pretty face, framed in those fair and girlish curls which had been the fashion of two decades previous, took on a thoughtful expression. “I do believe that you could … tho’ it would be a teeny bit barbaric, considering … I think, dear – that some means of participating in the Great Cause will come to you. An opportunity, a new means of being of use to the Cause. You will know it when you see it, Minnie Dear.

”Minnie snorted again, but just as Lolly had said – the opportunity presented itself within the week through the medium of a letter from her old school-fellow intimate, Mary Ashton Rice. Mary Rice had married a minister among the Congregationalists named Livermore and moved with him to take up a congregation in the western city of Chicago.

My dear Minnie, Mary Livermore wrote, I have a very dear friend here in Galesburg, Illinois, a respectable widow who has supported her family with a practice in botanic medicine since the death of her husband a year or two ago. Mrs. Bickerdyke is a most noble and public-spirited woman, who has undertaken to convey a sizable quantity of donations from this congregation and others to the aid of a field hospital established at Cairo on the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. She writes to me in much agitation, as the hospital is ill-organized, and the deprivation and suffering of those poor soldiers there is unspeakable. She asks for aid and assistance in this most holy of missions. My heart is torn, but I cannot leave my family, my duties here to the congregation and to the Sanitary Commission, and my dearest Mr. Livermore. Mrs. Bickerdyke is a most determined and forceful woman, a tower of strength amongst our sex. But she is in dire need of assistance in her quest to bring comfort to the sick and wounded, and I fear that many might find fault with her blunt manner of address. She is not known outside the small circle of her friends in Galesburg, and it occurs to me that you, with your long experience of nursing your father and brothers, your fame outside of a small circle, and your notable powers of earnest persuasion – that you may be perfectly situated to be of assistance to her in this time of dreadful need …”

Minnie sent a telegram in reply. “On my way to Cairo. Fond regards to Mrs. Bickerdyce and yourself.”

(From the work in progress … I am now reading my stacks of materiel on the American Civil War, and making notes for the next half of the book. In this excerpt, Minnie is introduced to a man who will soon become very important.)

“Auntie,” Richard Brewer asked one afternoon, on a mild spring afternoon some three years later, “There is a man I think that you would enjoy being introduced to – a Westerner, so you might not already be known to you or you to him, but he is fierce regarding the limits of the slave system, and not allowing it in those proposed new states.”

“I thought that I knew every prominent abolitionist that there is,” Minnie fretted. She and Lolly were preparing for another lecture tour, this time to Illinois, where the fight against the vile institution was fierce and unrelenting – nearly as fierce as it was in the Kansas and Missouri Territories, where the cause had already been baptized in blood – the blood of abolitionists and slavers alike. “But of course – when do you propose that we shall meet?”

“At our house, tomorrow evening for supper and a small gathering of like-minded among legal circles,” Richard replied, with a grin. “And I’ll have you know that he has expressed a desire to meet you, Auntie – the famed and impassioned lady lecturer.”

“I suppose that my attendance has already been assured?” Minnie asked, concealing a small sigh. She had yet to pack for this latest circuit of lectures, although Lolly had already made most of the travel arrangements. Lolly was incredibly thorough about such matters – a passing miracle for everyone who had ever thought of her as one of the most feather-headed females imaginable.

“Of course,” Richard assured her, with a bow over her hand. “And I think you will enjoy Mr. Lincoln’s company, enormously – he is one of the most entertaining and companionable gentlemen I have ever had the pleasure of spending a number of hours with – and could have spent twice as many in his company, while laughing like a fool.”

“Mr. Lincoln?” Lolly Bard exclaimed in delight. “Why yes – I know of him, and he is a delight, if it is he who is the chief legal counsel for the Illinois Central Railroad! Mr. Bard was a shareholder in that company you know, and I still correspond with many of his old friends! They think the world of Mr. Lincoln, if that is the same man…”

“It would be,” Richard agreed, “For he has practiced as a lawyer for many years, and was elected to state office, and served representing Illinois in Washington for a term. The word is that he is a formidable man, for all that he looks the picture of the ungainly country yokel, and never darkened the door of a schoolhouse after the age of about ten or so. They say he split rails and felled trees to earn a living, early on. You can imagine what our cultivated acquaintances will think of that!”

“Oh, my,” Minnie exclaimed. She could just imagine what some of the other erudite, comfortably monied and well-raised Bostonians would think and say of Mr. Lincoln, the country-bred, self-educated westerner. “But I have had occasion to meet many people, in my tours, Richard – and many of them in ragged working-men’s garb, who are more courteously-mannered and considerate than … then my brother Tem,” she added, for Tem, for all the wealth of Papa-the-Judge and the advantages of education, had often been waspish, rude and … not to put too fine a point on it, snobbish to a degree that would embarrass an English noble. “I would be honored to meet this prairie lawyer acquaintance of yours. If he is determined an abolitionist as you say, then he is already a man of whom I am inclined to think well!”

“I thought you would welcome the introduction,” Richard said, “As you and Mrs. Bard are venturing into the near west, in the next weeks. And I think that Mr. Lincoln will prove to be an important man, soon enough.”

Minnie privately thought that Richard exaggerated – she had met all sorts, when she was a girl, and Papa-the-Judge offered hospitality to a great many, either obscure or of note, but all interesting. She had met even more, as she had said to Richard, traveling from city and city, town to town, giving lectures on the iniquity of the slave system. But none of them were like Mr. Lincoln. Tem would have said he was sui generis, one of a kind, when she was presented to him in Sophie’s parlor; she and Lolly Bard and Mr. Lincoln were nearly the first arrivals. When Betty the maid opened the front door of the Brewer mansion, the sound of delighted laughter led Minnie and Lolly to the parlor almost at once, where Sophie and Richard sat with a tall, awkward gangle of a man clad in an ill-fitting suit, a man in intense conversation with Richie.

“… three boys,” Mr. Lincoln was saying, “You’d be right in between Robert and Willie … ma’am!” he added, upon seeing Minnie in the doorway. He and Richard both rose hastily from where they sat, and Richard performed the introductions, barely concealing his own amusement, as Sophie took Richie by the hand and led him out of the room.

“I am mos’ pleased to make your acquaintance, Miss Vining,” Mr. Lincoln bowed over her hand – a very disjointed bow, like a badly-strung puppet, for he was very tall, towering over Minnie like a tall tree – and she was barely taller than she had been at the age of thirteen. Rather to her surprise, his voice was thinner than she expected, a light tenor, like a boy whose voice hadn’t broken yet. His hands were powerful, the hands of a working man, who did more than just wield a pen; she sensed that he was particularly, purposefully gentle with her own hand, as she was in handling the birds, with their delicate bones, bones that could so readily be crushed without care taken. “I have read your articles in the Liberator with much interest, although I cannot honestly claim to be an absolutist when it comes to Abolition of the slave system.”

“You are not a reformer, then?” Minnie replied, somewhat surprised.

Mr. Lincoln smiled – he had a rather homely face, with knobby features and a great beak of a nose, but the smile transformed into a rather melancholy countenance, although the melancholy never really lifted from his eyes, deep-set as they were under a brow that the unkind would later liken to that of an ape.

“Of the Whiggish persuasion, Miss Vining – I would advocate for reformist measures in a slow and gradual manner, upon which most would agree.”

“But your feelings on the matter of slavery,” Minnie persisted.

“I would not be a slave,” Mr. Lincoln replied, thoughtfully, “And I would not be a master of slaves, either. It is a great injustice to be the first, and an insupportable moral burden to be the other …”

“That is exactly what was said to me, early on,” Minnie replied earnestly. “By one who had good reason to know. But what is the principle with regard to the vile institution that you hold to, without reserve?”

“This one,” Mr. Lincoln replied, with another one of those melancholy smiles. “That I would work to keep the institution from extending to those new territories of ours, which will become states, and very soon, I believe. They shall not have the stain of slavery marring them. And that is my governing principle, Miss Vining, although it may come about that I might be forced by circumstances to acquire others, as the situation suggests. Predicting the future developments in our world is a chancy thing, which would try the talents of a modern Nostradamus.”

“Indeed,” Minnie agreed, and Mr. Lincoln favored her with another one of those transforming smiles.

“Your late father, Judge Lycurgus Vining – he was a notable jurist in his day, was he not? A number of his rulings and arguments before the superior courts were cited in several of my independent readings … are you able to enlarge upon his reasonings in those matters? Mr. Brewer assures me that you were a student of your father’s dealings in that regard…”

“At another time, perhaps,” Richard Brewer intervened, as they heard Betty opening the front door to another guest. “We have invited all to a purely social gathering, Mr. Lincoln – not a meeting of the American Missionary Association.”

“Still,” Mr. Lincoln made a slight bow towards Minnie, and Lolly Bard. “I’d ‘mire to meet with Miss Vining again, and speak with me, concerning her reminiscences of her father, and of her observances of the slave system.”

“Of course,” Minnie replied – and she had been charmed beyond words, at meeting a man who might yet become an ally in the great cause – and who knew of and wholly admired Papa-the-Judge.

Recent Comments