Once there was a little town, a little oasis of civilization – as the early 20th century understood the term – in the deserts of New Mexico, a bare three miles from the international boarder. The town was named for Christopher Columbus – the nearest big town on the American side of the border with Mexico was the county seat of Deming, thirty miles or so to the north; half a day’s journey on horseback or in a Model T automobile in the desert country of the Southwest. It’s a mixed community of Anglo and Mexicans, some of whose families have been there nearly forever as the far West goes, eking out a living as ranchers and traders, never more than a population of about fifteen hundred. There’s a train station, a schoolhouse, a couple of general stores, a drug-store, some nice houses for the better-off Anglo residents, and a local newspaper – the Columbus Courier, where there is even a telephone switchboard. Although Columbus at this time is better than a decade and a half into the twentieth century, in most ways it looks back to the late 19th century, to the frontier, when men went armed as a matter of course. Although the Indian wars are thirty years over – no need to fear raids from Mimbreno and Jicarilla Apache, from the fearsome Geronimo, from Comanche and Kiowa, the Mexican and Anglo living in this place have long and bitter memories.

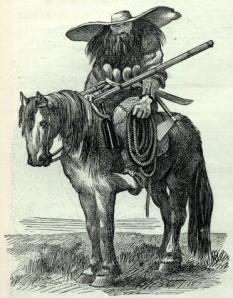

In this year of 1916, as a new and more horrible kind of war is being waged on the other side of the world, while a more present danger menaces the border; political unrest in Mexico has flamed into open civil war, once again. Once again, the fighting threatens to spill over the border; once again refugees from a war on one side of the border seek safety on the other, while those doing the fighting look for allies, supplies, arms. This has been going on for ten years. One man in particular, the revolutionary Doroteo Arango, better known as Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa had several good reasons for broadening the fight within Mexico to the other side of the border. Pancho Villa had (and still does) an enviable reputation as their champion among the poorest of the poor in Mexico, in spite of being a particularly ruthless killer. He also had been, at various times, a cattle rustler, bank robber, guerrilla fighter – and aspiring presidential candidate in the revolution that broke out following overthrow of more than three decades of dictatorship by Porfirio Diaz.

Once, he had counted on American support in his bid for the presidency of Mexico, but after bitter fighting his rival Carranza had been officially recognized by the American government – and Pancho Villa was enraged. The border was closed to him, as far as supplies and munitions were concerned. He began deliberately targeting Americans living and working along the border region, hoping to provoke a furious American reaction, and possibly even intervention in the still-simmering war in Northern Mexico. He believed that an American counter-strike against him would discredit Carranza. Such activities would renew support to his side, and revive his hopes for the presidency.

In this he may have been egged on by German interests, hoping to foment sufficient unrest along the border in order to keep the Americans from intervening in Europe. A US Army deployed along the Mexican border was a much more satisfactory situation to Germany than a US Army deployed along the Western Front along with the English and the French. Early in April, 1915, Brigadier General John “Black Jack” Pershing and an infantry brigade were deployed to Fort Bliss; by the next year, there was a garrison of about 600 soldiers stationed near Columbus, housed in flimsy quarters called Camp Furlong, although they were often deployed on patrols.

By March, 1916, Pancho Villa’s band was in desperate straits; short of shoes, beans and bullets. Something had to be done, both to re-supply his command – and to provoke a reaction from the Americans. The best place for both turned out to be . . . Columbus. After a decade of bitter civil war south of a border marked only with five slender strands of barbed-wire, that conflict was about to spill over. The US government, led by President Woodrow Wilson had laid down their bet on the apparent winner, Venustiano Carranza. Carranza’s sometime ally, now rival, Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa, who had once appeared to be a clear winner from north of the border – was cut off, from supplies and support, which now went to Carranza. Pancho Villa had been so admired for his military skills during the revolution which overthrew the Diaz dictatorship that he was invited personally to Fort Bliss in 1913 to meet with General Pershing. He appeared as himself in a handful of silent movies . . . but suddenly he was persona non grata north of the border, and one might be forgiven for wondering if Villa took it all as a personal insult; how much was the deliberate killing of Americans a calculation intended to produce a reaction, and how much was personal pique?

Villa and the last remnants of his army – about five-hundred, all told – were almost down to their last bean and bullet. In defeat, Villa’s men increasingly resembled bandits, rather than soldiers. The high desert of Sonora was all but empty of anything that could be used by the Villa’s foraging parties, having been pretty well looted, wrecked or expropriated previously. There were only a few struggling ranches and mining operations, from which very little in the way of supplies could be extracted, only a handful of American hostages – the wife of an American ranch manager, Maude Wright, and a black American ranch hand known as Bunk Spencer. Some days later, on March 9, 1916, Villa’s column of horsemen departed from their camp and crossed the border into New Mexico. In the darkness before dawn, most residents and soldiers were asleep. At about 4:15, the Villistas stuck in two elements. Of those residents of Columbus awake at that hour, most were soldiers on guard, or Army cooks beginning preparations for breakfast, and the initial surprise was almost total. A few guards were surprised, knifed or clubbed to death – but a guard posted at the military headquarters challenged the shadowy intruders, and the first exchange of gunfire broke out – alerting townspeople and soldiers alike.

The aim of the well-organized Villistas was loot, of course – stocks of food, ammunition, clothing and boots from the civilian stores, and small arms, machine guns, mules and horses from the Army camp. To that end, Villa’s men first moved swiftly towards those general stores. Most of the structures in town and housing the garrison were wood-framed clapboard; in the dry climate, easy to set on fire, and even easier to break into, as well as offering practically no shelter from gunfire. But the citizens and soldiers quickly rallied – memories of frontier days were sufficiently fresh that most residents of Columbus kept arms and ammunition in their houses as a matter of course. Even the Army cooks defended themselves, with a kettle of boiling water, an ax used to cut kindling and a couple of shotguns used to hunt game for the soldiers.

Otherwise, most of the Army’s guns were secured in the armory, but a quick-thinking lieutenant, James Castleman, quickly rounded up about thirty soldiers who broke the locks in the armory and took to the field. Castleman had been alerted early on, having stepped out of his quarters to see what the ruckus was all about only to be shot at and narrowly missed by a Villista. Castleman, fortunately had his side-arm in hand, and returned fire. Another lieutenant, John Lucas, who commanded a machine-gun troop, set up his four 7-mm machine guns. The Villistas were caught in a cross-fire, silhouetted against the fiercely burning Commercial Hotel and the general stores. The fighting lasted about an hour and a half, with terribly one-sided results: eight soldiers and ten civilians, including a pregnant woman caught accidentally in the crossfire, against about a hundred of Villa’s raiding party. As the sun rose, Villa withdrew – allowing his two hostages to go free. He was pursued over the border by Major Frank Tompkins and two companies of cavalry, who harassed Villa’s rear-guard unmercifully, until a lack of ammunition and the realization they had chased Villa some fifteen miles into Mexico forced them to return.

Within a week, the outcry over Villa’s raid on Columbus would lead to the launching of a punitive expedition into Mexico, a force of 4,800 led by General Pershing – over the natural objections of the Carranza government. Pershing’s expedition would ultimately prove fruitless in it’s stated objective of capturing Pancho Villa and neutralizing his forces – however, it proved to be a useful experience for the US Army. Pershing’s force made heavy use of aerial reconnaissance, provided by the 1st Aero Squadron, flying Curtiss ‘Jenny’ biplanes, of long-range truck transport of supplies, and practice in tactics which would come in very handy, when America entered into WWI. Lt. Lucas would become a general and command troops on the Italian front in WWII. Lt. Castleman was decorated for valor, in organizing the defense of Columbus, and one of General Pershing’s aides on the Mexico expedition – then 2nd Lt. George Patton, would win his first promotion and be launched on a path to military glory.

Pancho Villa would, when the Revolution ended in 1920, settle down to the life of a rancher, on estates that he owned near Parral and Chihuahua. He would be assassinated in July, 1923; for what reason and by whom are still a matter of mystery and considerable debate.

Recent Comments