AVAILABLE DIRECT FROM THE AUTHORS

AUTOGRAPHED WITH A PERSONAL MESSAGE

Each $13.25 + S/H and Texas Sales Tax

Or Both together for $24.00 + S/H and Texas Sales Tax

![]()

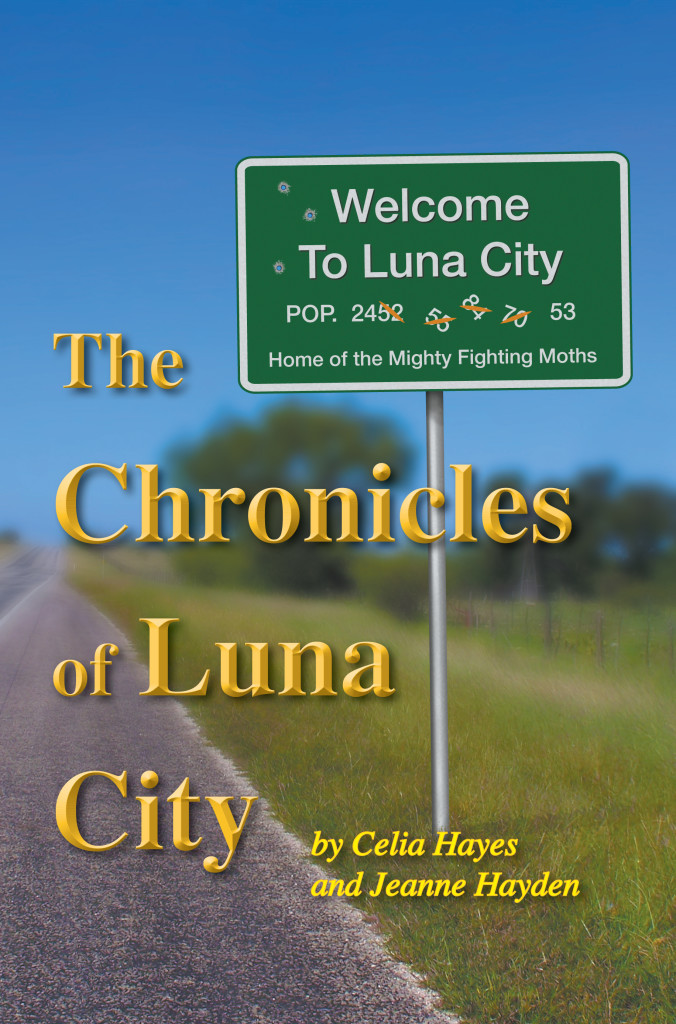

The Chronicles of Luna City – Available also through Amazon – in print and Kindle

And at Barnes & Noble

The Second Chronicle of Luna City

In print and Kindle on Amazon

And at Barnes & Noble

Sample Chapter from The Second Chronicle of Luna City

Things That Go Bump in the Night

It gratified Richard no end, to discover that there were a number of weeks – months, even – during which it was possible to be comfortable in the little Airstream without running the air conditioning or heating. It seemed at first, that Texas had only two temperature settings; Broil/Roast and Blazingly Hot. To someone accustomed to the fairly mild summers of Northern Europe, alternated with the occasional frigid winter blast, it had all come very much as a shock, especially when such extremes could sometimes be experienced within a single day. However, once he discovered that autumn, winter, and spring were very much like an English summer, he was prepared to be more philosophical about it. The only bad thing about leaving the windows of the Airstream open at night, for the fresh air was the occasional scream of a pea-fowl who preferred to roost in a nearby tree, (until he took steps to discourage the blasted creature), the distant crowing of the Grant’s half a dozen roosters, and now and again something that sounded like a dog suffering from fits of nervous laughter.

“Coyote,” Sefton Grant explained to him, the morning that Richard first mentioned this. Sefton, who was lean and stringy and looked like a slightly younger, fitter and less run-to-seed Willie Nelson, was putting out morning feed for the goats, clad in his usual working attire of battered cowboy boots, a pair of baggy cut-off jeans and a wide-brimmed ‘boonie’ hat which had once been military green but was now weathered to no particular color at all, and nothing much else besides. “Yeah, there’re are coyotes all over in the brush. You won’t see them in the daytime, though.”

“Do they present any danger?” Richard asked, nervously – since he had coyotes and wolves rather muddled in his own mind.

“Only if you are a housecat, or a chicken,” Sefton replied, grinning. “That’s why we lock up them both at night, and give the dogs free run. Judikens says that the coyotes gotta live, too … but not on our damned chickens.”

The dogs – a couple of houndish-looking mutts and one which looked rather like a standard poodle – were usually to be found lazing in any convenient patch of sunshine in the Grant’s yurt-centered compound, where they had all found a happy refuge. Richard didn’t think any of the three were energetic enough to be effective guard dogs, but you never knew. The Grants hadn’t selected the dogs for particular guarding-skills in any case; it was more a case of the dogs – all strays or cruelly dumped in the countryside by irresponsible owners – selecting the Grants as their chosen humans.

“The goats now,” Sefton added, with some satisfaction. “They look after each other. Don’t worry about anything you hear at night, Richard – the dogs are on guard.”

This conversation was the first thing to come to Richard’s mind – actually the second thing, after, “What the hell was that?” – when something woke him in the middle of the night. Something; he sat up in the dark, trying to recollect what it was, or might be. Yes, a sudden kind

of ‘whumping’ noise, as of something heavy hitting the ground. Without turning on any of the interior lights, he slid out of bed and padded through to the front of the caravan, where the larger windows offered views of the goat pastures, and the lumpy meadow leading down to the river, with the forlorn campground bathhouse and lavatory, standing foursquare with moonlight silvering the white-washed walls and tin roof. The moon drifted, a milk-pale orb, above the tree line at the water’s edge, where mist tangled like shredded gauze among the distant shrubs and stands of rushes. Was there something moving, there among the brush? Something white; Richard was not certain of what, exactly. Could it be Azúcar, the Grant’s infamously bad-tempered pet llama?

He shrugged – likely it was. Well, no matter to him; and Azúcar was big enough and sufficiently aggressive to look after himself very well. Richard would have thought no more about it – and then he recalled what Araceli had said about ghost riders, along the bank of the river at full moon. Nope – didn’t look anything like ghost riders on spectral horses at all.

But something woke him the following night; not the ‘whump!’ noise that he had heard before. This was more like a regular squeaking sound, like a supermarket trolley with a bad wheel. It went on for about fifteen minutes, finally diminishing into silence, and Richard went back to sleep, muzzily thinking to himself that it was someone passing in the street below … only to recall upon waking very early – that there was no street and no ‘below’ from an Airstream caravan parked in a deserted campground. This was curious at the very least. He could not be certain that it wasn’t a dream anyway.

He mentioned it to Araceli, about mid-morning, when the breakfast rush was over.

“I’ve been wakened in the early morning, a couple of times,” he ventured. “The place is usually so quiet that I sleep like a log … but there is something queer going on.”

“Not that,” Araceli said, in much alarm. “Judy and Sefton are nudists… and totally against any kind of exploitation in any form!”

“No, not that,” Richard sighed. “Not the way that it sounded. It’s just

… odd. The place is quiet as a tomb, when the old commune or Founder’s Day isn’t in session. But I can’t help thinking that something strange is going on. Two nights in a row, and something waking me up in the wee hours.”

“Not the ghost riders, is it?” Araceli ventured. “That’s a tale told by teenagers to frighten each other or by the abuelitas to frighten disobedient children.”

“The ghost riders?” Richard raised a skeptical eyebrow. “Pull the other one, Araceli my sweet country innocent. Britain is haunted several times over every inch by the ghosts of two thousand years. I doubt that there is a square inch of the place completely un-haunted. Spectral riders, of a mere hundred and fifty years’ provenance? Please.”

“Well, you’re living there, you figure out a way to put up with them,” Araceli replied smartly and then their conversation wandered on, perforce, to more immediate topics.

But on the next night, Richard was wakened again. This night was a one where a storm front had blown through, dropping quantities of rain, and now the warmer temperatures were bringing moisture up from the ground and the water. The entire campground was shrouded in mist. It was not quite solid enough to be called a ‘fog’ – but it did wrap the low- lying area adjacent to the river-bottom in a silvery-white veil. And there came that same squeaky-wheel sound again. Only this time, he recognized it for what it undoubtedly was – the hand-cart that Sefton hauled heavy things like goat-fodder and straw bedding from the yurt compound to the series of ramshackle sheds which sheltered the goats in bad weather.

“I wonder what the old berk is up to?” he wondered. Well, nothing much could startle him with regard to Judy and Sefton, but why they were doing it in the middle of the night was a puzzlement. On that note, he rolled over and went back to sleep. He did make mention of it, the following afternoon, after bicycling home from the Café. He stopped at the yurt to ask for half a dozen eggs for himself.

Judy beamed at him, saying, “Sure – let me see what the girls have produced! Can’t get any fresher than straight from the hen’s butt, can we?”

“No, I think not,” Richard replied, slightly unnerved by Judy’s way of putting it and also by a sudden mental vision of a hen on a gynecologist’s examining table, with feet in the stirrups. She bustled off towards the henhouse, as Sefton came around from the main shed, rolling the wheeled cart before him.

“’Lo, Rich,” he said. “How’s it goin’, man?”

“Pretty well,” Richard answered. “Getting ready for the mid-summer solstice?”

“Yep. We’re hoping for a good turn-out this year. The weather’s gonna be nice.” Sefton scratched his slightly bristly cheek with a faint scratching sound, and Richard suddenly recollected the sound of the cart, from the previous night.

“You might want to lock up that cart,” he said. “I could swear that someone has been using it at night. I keep hearing someone or something out in the campground in the wee hours.”

“Do ya?” Sefton shrugged, as if this was of little concern. “No one locks up anything around here. Mebbe ya heard the ghost riders, ‘r something like that.”

“Maybe,” Richard agreed. There were large bottles of something in the cart, large, opaque plastic bottles, mostly covered by other bags of wood-shavings used for bedding the hens and goats. But not quite … and he did wonder why Sefton headed off to the goat pasture as soon as Judy emerged from the henhouse with a wire basket of eggs.

And that night, he was wakened again – this time, not by a squeaking wheel, but by a strange kind of ‘chuff-chuff-chuffing’ sound. Without turning on any lights, Richard padded silently to the banquette end of the caravan and looked out into a world of fog and mist, an eldritch world in which a single small light flared and bobbed. Up and down across the length of the deserted campground, bobbing as a man might walk with a small light affixed to his forehead, the regular ‘chuff-chuff’ noise now close, now distant and nearly inaudible.

“Good night, nurse!” Richard said to himself, having finally realized what he was seeing. He watched for a bit longer; until the figure in white, the small light bobbing in the fog passed close enough to the caravan for him to be absolutely certain. And then he went back to bed, and slept the sleep of a man with a completely unworried mind.

In the morning, before the sun was more than a brief bright line on the eastern horizon, he went to the nearest goat shed with a battery torch in his hand. The small goats nuzzled at him in mild curiosity, and Che the now full-grown Nubian goat butted his thigh as if demanding the caress that was only his due.

Buried deep in the goat’s bedding in the second ramshackle shed were some very curious items. And when Richard returned home that afternoon – how very strange to think of the Airstream as home! – with small shreds of bread dough still clinging to his hands, a dusting of flour on his shirt and in his hair from the weekly preparation of an enormous batch of cinnamon rolls, he put up his bicycle and wandered over towards the yurt. He was exhausted from the day of work, which had begun before dawn, and from pedaling the bike, for the summer heat was merciless, but he had just enough energy to look for Sefton.

He found him shoveling the latest accumulation of chicken dung into the serried rows of reeking piles that were the Grant’s compost heaps. (Used and reused wooden pallets, strung together in fours to make individual compost containers.)

“Hard at work, I see,” Richard observed, and Sefton hesitated and grinned – an expression which vanished completely from his bronzed countenance as soon as Richard added, “Near to twenty hours a day, that I can see, after last night.”

“Er …” Sefton went several shades paler under his tan. “What did you … it was foggy last night. That’s when people see the ghost riders! Judikens says that …”

“Likely she could see the whole mounted parade of Horse Guards, given the right encouragement,” Richard drawled. “But what I saw was someone in a white cover-all, walking around fogging the whole place with insect-killer and the whole lot of bug-killer and fogger is presently hidden under the goat’s bedding materiel in the second shed where you left it in the wee hours.”

Sefton recovered something of his composure, squinting at Richard. “There hasn’t been anyone living in the trailer long-term since the commune broke up, so there ain’t no way that anyone took note before. Well, you know how Judikens makes such a big thing about natural remedies, and chemicals. She’s been big on it for years, tell the truth. But the truth of it is that folk that are not used to the outdoors much; they can get sort of over-exposed, real easily. You know; mosquitoes. Fire ants…”

“Yes, I recollect that, very clearly,” Richard answered with a reminiscent shudder. On his very first morning in Luna City, he had awakened from drunken slumber, lying naked on top of a large fire-ant hill on the riverbank, with predictable results. It had taken nearly two weeks for the small pustules left wherever they stung him to heal entirely. “So, the usual environmentally-sensitive stuff that Judy wants us to

use doesn’t make a dent,” Sefton looked at Richard – not quite imploring, but inviting comprehension. “And we can’t have our guests, our old friends bitten six ways from Sunday. I do what needs to be done – been doing it for years, without her knowing. Hell, she was raised in the suburbs, had no idea of what farming and raising stuff really meant when we first came here. I did; I grew up on a ranch, outside of a little burg called Noodle … ever hear of it?”

“Can’t say I have,” Richard managed to swallow his astonishment. “Really – there’s a place in Texas called Noodle?”

“You betcha,” Sefton nodded. Richard thought about it some more, wondering for almost the first time how Sefton and Judy became a pair. A more oddly-assorted couple was hard to imagine.

Sefton answered the unasked question. “We were at UT, together. A thing, ya know? Turn on, tune in, drop out. Summer of Love, and all that. My folks were almighty pissed – hers’ too. I was supposed to be studying agronomy. But Judikens had a way with her. Crook her little finger, guys come running. Goddess-power, ya know?” Sefton leaned against his shovel and sighed, reminiscently. “It seemed like the world was on fire, falling apart. We had to get back to the garden, get in touch with nature, withdraw from the materiel world an’ all. So, Judikens had this little piece of worthless, overgrown land she inherited, and we had the notion to set up a commune on it.” Sefton chuckled, wryly. “Yep – buncha college kids with a load of airy-fairy notions. Took most of the summer to kick that nonsense out of them. But us two – we stuck to it. No, it ain’t much to look at, and I’m the first to admit it. But we don’t owe nothin’ to the man, and we don’t call anyone boss. We’re off the grid, got plenty to eat, a roof over our head. We get by – you know what they say ‘bout how country boys can survive? Heck, I wish that Judikens was a better cook, but I’ll bet there are folks like Mister Clovis Walcott who might live under a better roof’n ours, but aren’t any happier. You don’t wanna give me away, do ya?”

“My lips are sealed,” Richard replied, with perfect contentment. “I promise, I will say nothing to cause domestic dissention between yourself and your good lady. I have no great love for either mosquitoes or fire ants.”

“Thanks, Richard,” Sefton beamed at him. “It ain’t much, but it’s home … an’ you’re a part of the family.”

“Looks like we’re going to get another member of it, by extension,” Richard observed. From where they stood, by the henhouse and the compost enclosures, they could see a battered RV crawling carefully down the rutted dirt road which led from Route 123 towards the campground enclosure. “Is this anyone you know?” he added, for Sefton had mumbled something uncomplimentary under his breath, upon noting the large logo applied, as a banner across the side of the RV. “Treasure Hunters, International” it read, in ornate letters, with a website in slightly smaller letters underneath and a portrait representation of a beaming, bearded gentleman alongside the logo.

“Yep,” Sefton replied, and spat into the weeds which fringed the compost piles. “Xavier Gunnison Penn, the world-champion treasure- hunter as he calls himself. He’s been coming here for years, looking for Charley Mills’ treasure hoard. I’ll bet that Araceli Gonzales’ little boy finding a gold coin in the Easter Egg hunt has fired him up all over again.”

“He’s been here before?” Richard was frankly astonished; the only regular visitors to the Age of Aquarius were either members of the old commune on their regular mid-summer pilgrimage, or out-of-town residents returning for Founders’ Day – in either case, visitors knowing well what fresh hell awaited. He had yet to see a casual traveler pull off the main road and find their way to the overgrown meadow; if they did, turning around and driving away as soon as they saw the place, as fast as they could risk their tires and shock absorbers on the rutted unpaved track. Now Sefton nodded glumly. “Yep. And aside from being about six kinds of nut, he’s a cheap bastard. Guess I’d better call Joe Vaughn and let him know.”

“He’s not some kind of criminal, is he?”

“No, not that you’d notice so much,” Sefton hesitated. In the campground, the RV trundled slowly across to the far edge where the single row of electric hook-ups was situated, several spaces down from the Airstream. The RV halted, then backed slowly into the space. “It’s just that he’s one of these enthusiasts. No discretion. Some crazy notion pops into his head, he’s going with it three seconds later.”

The driver-side door of the RV opened, and a man emerged; short, stocky and bearded. He saw the two of them and waved, not with any urgency. As the driver – presumably the impulsive Mr. Penn – went around settling the RV hook-ups, Sefton continued, “You ever hear how he got banned for life from the Smithsonian? I’ll tell ya; I know it’s a fact because he told me the story himself. He got it in his head that there was a map to a treasure, etched on the inside of one of those big dinosaur bones. And nothing would do but that he had to look at it, right that very moment. So, he jumped over the rope and shinnied up into the exhibit. You know – into it! One of those big bastards in the main exhibit hall. You gotta know that everything and everybody all around went all kinda ape. He got into a fist-fight with a nice lady docent, right on the spot, and that was when they banned him forever.”

Sefton shook his head, sadly. “You know, any real sensible person woulda asked permission, written a letter asking real nice, pretty please. So, if he gets some sorta notion to pop over to the Wyler’s or to Mills Farm with his metal detector and a coupla shovels, try to talk some sense into him. And if you can’t manage that, then don’t let him talk you inta going with him.”

“I will keep your wise advice in mind,” Richard replied. “Consider me warned. And thank you once more for the midnight mosquito- slaughter. Judy might not approve, but I do, most enthusiastically.”

“No problem,” Sefton grinned, revealing a most unexpectedly healthy set of good teeth. “Say, I know you’re a two-fisted drinking man. I got a good batch of mustang grape wine made a couple years ago – k’n I bring you a coupla bottles, as a token of my esteem?”

“Certainly,” Richard answered – really, considering some of the swill he had pounded down in his time, how bad could mustang grape wine really be – and what was a mustang grape anyway? He devoutly hoped that it wasn’t some kind of rural slang, like road apples for horse droppings.

“Great!” Sefton replied. “Soon as I get finished with this, I’ll bring it over.” He looked over at the RV with the Treasure Hunters banner across the side, and sighed, his features returning to their usual expression of lugubrious gloom. “Guess you’ll be seeing how long it takes for Gunnison Penn to come over and make friends, Rich. Inside-outside, about two minutes is my bet. Sorry ‘bout that. But as Judikens says, it’s our sacred obligation to make strangers welcome at the Age of Aquarius.”

“A concept to be heartily embraced by all in the business of providing hospitality to the public,” Richard answered, unable to think of anything else to say. He bade farewell to Sefton and strolled down the gentle slope to what he had begun to think of as home. Over the past fifteen years of his life, he thought – the old Airstream was the one place in which he had remained in residence for the longest unbroken period of time – a straight eighteen months. On that account alone, good reason to think of it as home. All the better reason to defend it – and by extension, the Grants, eccentric as they were, and as inconvenient as Che the goat and the unbearably noisy pea-fowl – that beast which had taken to roosting nightly in the tree adjacent to the Airstream and rousing Richard at ungodly hours with its’ incessant screaming. Still … if he had his old income at his command, he could purchase the Airstream from the Grants, and move it to … no. To change anything about his situation was to make it something less than what he had become comfortable in.

He opened the door and closed it behind him, relishing as always the cool air inside which came to meet him, the tiny, tidy and comfortable interior; a quiet place to eat, sleep, and read Larousse Gastronome, to sit in the banquette seat, or in one of the patio chairs outside and watch the sun go down, after a long and rewarding day of work in the Café. Yes, he was a self-centered bastard. Never mind about the subjugation of enemies and listening to the lamentations of their women – life’s greatest pleasure to him was watching the sun set on a day of honorable and rewarding work … oh stone the bloody crows, was that someone tapping on the door?

He opened the rounded-corner trailer door – yes, of course; there stood the driver of the Treasure Hunter RV. He was a gentleman of late middle age, balding above, and extraordinarily hirsute below the nose – which organ was large and curved like a parrot’s beak. He was clad in khaki shorts and an eye-wincingly multi-colored Hawaiian-style shirt patterned in palm-trees and electric pink canoes, alligators and hula-skirt clad dancing girls.

“Hi, neighbor,” this person said. “Do you have a pint of milk to spare?”

Recent Comments